Branko Milanovic looks at the big picture.

During his dozen years as chief economist of the World Bank’s Research Department, he focused on making sense of the all-important economic question that many economists, paradoxically, seem uninterested in: How are people doing?

It’s a deceptively difficult question. To answer it you must determine what you mean by “people.” The average person? The median household? The poorest of the poor? The 1%?

Much also depends on the economic state of various countries and how living costs can be compared across nations. Determining how any one group of people is doing depends on how they rank among neighbors and rivals.

Set to be published next month (April 2016) Milanovic’s new book, Global Inequality, goes well beyond the narrative of rising inequality captured by French economist Thomas Piketty’s surprise 2014 best-seller, Capital in the Twenty-first Century. In his highly readable account, Milanovic puts that development into the context of the centuries-long ebbs and flows of inequality driven by economic changes, such as the Industrial Revolution, as well epidemics, mass migrations, revolutions, wars and other political upheavals.

Milanovic, currently at the Luxembourg Income Study Center at the City University of New York, visited Quartz to talk about his book and its implications, including the decline of the US middle class, why the Black Death leveled the economic playing field, and the rise of Donald J. Trump. Here are edited excerpts of our conversation.

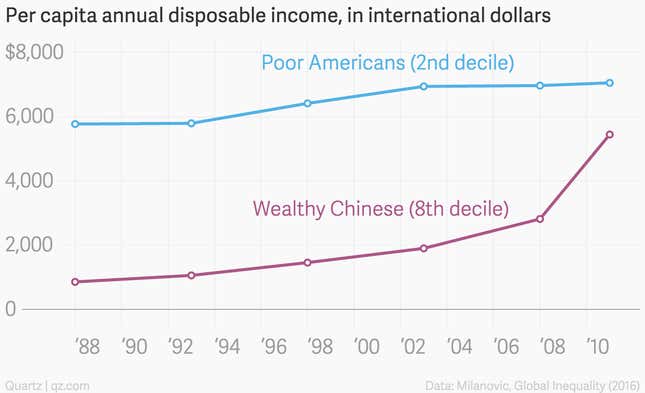

QZ: Your book opens with this mind-blowing chart. As I understand it, the short version is the middle class in the rich world—mostly the US and Europe—have seen their incomes flat-line.

But both the global super-rich and the middle class in the emerging markets, seen huge gains. Is that about right?

Milanovic: This is about right. You have large increases in real income, which is really the middle class in Asia, essentially. (China, but not only China, it’s also India, Indonesia, Vietnam and so forth.) And the global top 1%.

And the third point, which is obviously very important, is the absence of growth among the lower middle classes, or middle classes, in Japan, Germany and the US.

So the affluent countries’ middle classes have seen very little income growth.

It really shows you that these classes are under double pressure. They’re actually having pressure from the middle classes of developing Asia, because they are competing for jobs, as we know in the US. But they’re also, to some extent, under pressure from their local plutocracy, because [the top 1% of earners] have done so much better than them. So basically I think the chart also shows you the dilemmas we’re dealing with in the rich world.

What does this add to what we know from Piketty’s charts, which show inequality rising back to where it was in early 20th century?

Where they kind of join each other is the fact that they both show this really emerging gap, or abyss, if you will, between the middle classes in the rich world and the very rich, the top 1% in the rich world. So that’s the point of commonality between the two.

Falling inequality is supposed to be a good thing. But as your book points out, historically, inequality often fell because something catastrophic happend: Diseases, wars, civil breakdown. The decline most recently was because of events like the Great Depression, World War II. So how how does inequality relate to overall welfare?

Milanovic: I think what I introduce there, as you mention, is “malign” and “benign” forces [that can drive inequality]. The benign forces are increased education, movement to the cities, more people being educated and the skill premium being less, aging of the population, demand for social services and protection. And all of those would reduce inequality. And that is a good thing. That would be a benign decline in inequality.

That’s a good thing.

That’s good. But we know historically that inequality often actually went down because of malign forces. Historically, it was epidemics and plagues. That was quite well-documented. It led to a decline in inequality simply because labor became scarce.

So the Black Death in Europe killed so many people that there weren’t as many workers, and wages rose.

It did actually increase the wage rate. But at the cost of killing millions of people. The same thing actually is true with the two World Wars, because they led to a massive mobilization of the labor force, an increase in taxation, destruction of property, and the destruction of capital incomes.

But obviously, mankind’s objective is not to reduce inequality by destroying the world. But we have to actually acknowledge the fact that sometimes malign forces can lead to the reduction in inequality—which obviously is not the most desirable thing.

Your book is very interesting because it blends together things that people might not think of as strictly economics. You argue that a lot of these malign processes have some economic roots.

I actually believe that strongly. In the context of World War I, it was that actually the economic processes which were happening—particularly in the large countries, most importantly the UK, Germany and France—which I think precipitated this run to the war.

The book seems to suggest that inequality can drive politics. Do you see that today? Does inequality help explain Donald Trump?

Definitely. For Donald Trump I would say it’s an easy question.

It was really absence of growth, stagnation of incomes in the US middle class, not only from loss of jobs, but also from loss of dreams of upward mobility for many people. Or perhaps because of imports, or because of direct competition with Asia or other emerging markets. So that was clearly one strong element which explains Trump. I would stop there. But I would actually like to continue on a second point.

Please go ahead.

I don’t want to go into some kind of catastrophic scenarios. But, if you see inequality driving political processes within countries, it might also have repercussions worldwide. Because there may be some parts of—how should I say, the different social groups—that have interests in sort of aggressive foreign policy and wars and so on. So you know it actually can spillover into a conflict. Again, I don’t want to say it will be necessarily like that, but it could be a conflict like World War I.

You also make this point about the shrinkage of the middle class. You say the decline has been particularly striking in the US.

Once you agree to one definition the data all show you for the US—and for the other countries—but for the US in a striking fashion, that the middle class has gone down percentage wise, and secondly, its income relative to the mean income of the US, has gone down.

If someone expresses some anti-trade sentiment, people will often say, “Well, trade is not what hurt the American middle class. It’s technology. It’s not globalization.” You make the point in the book that technology and globalization, to a large extent, are the same thing. Can you explain?

We can think of technological development and globalization as, conceptually, two different things. But when it comes to the real life, they’re really almost the same.

Let me give you an example. People very often say that technological change happened because capital goods became cheaper. So it’s basically because, your laptop used to cost $6,000. Well, now of course you can get it for $400.

So, capital goods became cheaper. And you can say, “Well, that’s technological development. The chips became much better, and so on.”

But in reality what also happened is that you were also able to employ labor that was very cheap in Asia to produce these things—the chips and everything else—at very low cost.

So what you can actually call “technological development” was only made possible because you had globalization and cheap labor. If you had to use labor in the US at $15 an hour, or at a minimum wage, that labor would still keep that laptop at the price of, I don’t know, maybe $2000. So in that sense, you cannot disentangle the two. Because they often go together.

In other words, globalization is an enabling force for technological development. I see the two of them as complementary. So you cannot really separate the two in a meaningful way.

In your book, you bring up this notion of the citizenship premium, meaning that just by virtue of being born in the US, my lifetime income will be 93 times higher than someone who was born in Congo, one of the world’s poorest countries. How does this notion of a citizenship premium tie in to the massive migrations were seeing all over the world right now?

If you’re born in the US or a rich country, the exact same individual, you’re going to have much higher income than if you’re born in a poor country over your lifetime. That’s very clear.

[Migrations] respond to economic forces. So I really think it’s absolutely crucial that we see it as a reflection of this global inequality of incomes. That’s why we see people building walls and borders. Unfortunately, because there is such a high difference in average incomes the only way you can prevent people from coming somewhere is by building a wall. So that’s a cost of inequality.

And this brings us back to politics and Donald Trump. That’s literally what he’s talking about.

I actually wrote this book before the Trump phenomenon. But it’s such a perfect illustration. Because what you see is that ills of the middle class in the US are basically connected to globalization and competition with cheaper labor from Asia and immigration.