Moleskine, the Milan-based maker of cardboard-bound notebooks meant to evoke an earlier era of the Parisian arts scene, is going forward with an initial public offering on the Italian Stock Exchange. It’s a rare IPO for Italy’s struggling economy, but Moleskine’s owners think they can sell the public on the growth prospects of a beloved luxury brand whose stock-in-trade is paper. The offering could value Moleskine at up to €560 million ($722 million).

This week Moleskine began the process of pitching itself to investors before the stock begins trading on April 3. It filed a 771-page prospectus (PDF in Italian) that offers the first detailed look at the company, which fell into the hands of private equity in 2006. Here’s what we learned from that filing along with reports by the banks running Moleskine’s IPO—Goldman Sachs, UBS, and Mediobanca (PDFs in English)—and other sources.

A brand without a country

First things first: How is Moleskine pronounced?

Officially, however you want. The company says that because Moleskine has an “undefined national identity”—it was derived from French, popularized by a Brit, headquartered in Italy, and sold across the world—you are welcome to say MOLE-skin, mole-SKEEN, mole-ay-SKEEN-ay, or whatever variation suits you. Can you imagine Louis Vuitton or Hermès being so liberal with the pronunciation of their brands?

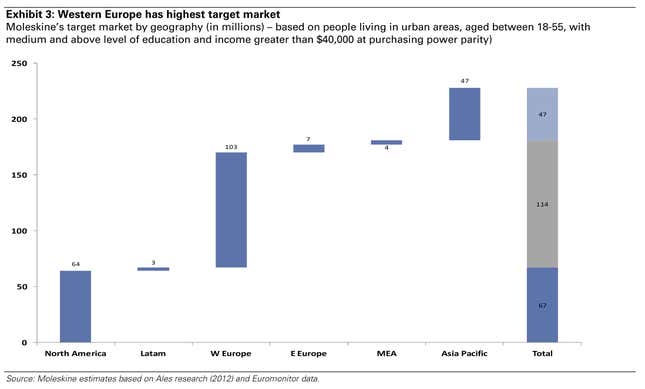

But this isn’t just a question of phonetics. Moleskine’s proclaimed statelessness is unlike most luxury brands, which often identify strongly with a place, but is very much in line with the recent emergence of a ”transglobal community of peers who have more in common with one another than with their countrymen.” There are only so many of these truly global citizens but many more who fashion themselves citizens of the world from the comfort of their living rooms. Moleskine figures it has 228 million potential customers, about half of whom are in Europe. Goldman Sachs breaks down the market by region:

According to the company, 3.3 million people, or 1.5% of its potential customers, have purchased a Moleskine product in the last 12 months, which either means it has plenty of room to grow or will always be a niche product.

Moleskine’s identity as a brand without a country fits, as well, with its origin story, which is printed on ecru paper and slipped inside most of its products. The iconic notebooks, bound in coated cardboard and kept closed with an elastic band, were first made by Parisian bookbinders in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when the city’s creative class was largely comprised of expats. Moleskine likes to brag that the notebooks were favored by Oscar Wilde, Pablo Picasso, Ernest Hemingway, and other notable artists who had transplanted to Paris.

The term “moleskine” was used by British writer Bruce Chatwin to describe the notebooks in his 1986 novel The Songlines. In 1997, a Milanese stationer, Modo & Modo, began producing the notebooks again, using Chatwin’s coinage. The company was bought by the French bank Société Générale in 2006, with later investments from two private equity firms, Italy’s Syntegra Capital and Switzerland’s Index Ventures. It’s transglobal business development.

Moleskine, incidentally, has been opening retail stores in train stations and airports, like the one in the video below at Heathrow’s Terminal 4. “The very essence of these places is one of transience,” the company says in florid marketing material, “origin and destination, start and finish, arrival and departure converge.”

The incredible margins of selling luxury paper goods

Moleskine’s operating margin, its profit as a percentage of revenue, was 41.7% last year. That compares favorably—indeed, very favorably—to the luxury brands the company considers to be peers, like luggage-maker Tumi (19.7%), fashion firm Prada (27.2%), and beauty-product boutique L’Occitane (16.7%). It’s not hard to see why. The raw goods of Moleskine’s paper products, which represent 93% of the company’s revenue, are cheap compared to most luxury wares, so there’s more room to mark up the price.

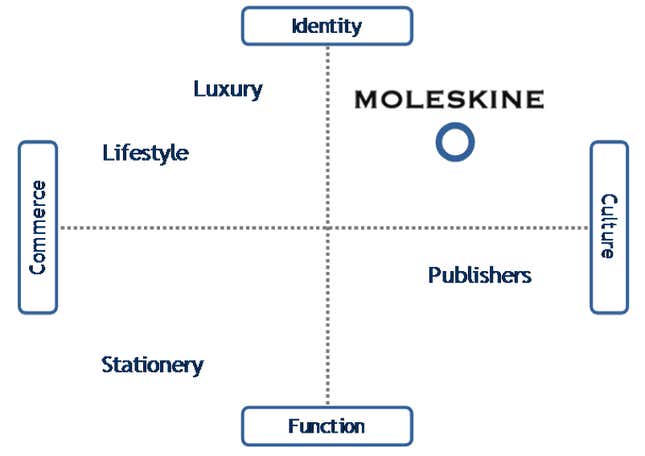

The higher margins are being used by Moleskine’s bankers to justify a valuation between 22 and 29.1 times the company’s earnings last year, which is higher than brands like Burberry and Richemont. But is Moleskine best compared to all these luxury brands, which sell clothing and accessories, or companies that actually make, you know, paper? An illuminating chart from the company’s IPO prospectus makes the case that Moleskine is actually the opposite of a stationery company:

Wrap your head around that for a second. Here is the company acknowledging that it doesn’t so much sell notebooks as it does a sense of identity and culture. But that’s the essence of luxury brands: they don’t sell physical goods so much as the notions that the goods are supposed to represent. These intangibles—”culture, design, imagination, memory, and travel,” according to the company’s bankers—are a better business to be in than paper.

Moleskine, by the numbers

Moleskine breaks down its products into three categories:

- 93% of revenue comes from 635 varieties of paper products, including the classic notebooks and related items like diaries and planners. The best-selling product is Moleskine’s classic hardcover ruled notebook, which generates 9% of sales.

- 7% of revenue is generated from a newer line of non-paper goods that includes pens, backpacks, and glasses. That’s not much, but Moleskine only started slapping its logo on these products in 2010.

- 0.4% of revenue—or pretty much nothing—comes from Moleskine’s nascent digital unit, which includes an app for the iPhone and iPad. Moleskine projects this will grow, but it’s hard to imagine the company will or should do much of a digital business.

Moleskine customers break down this way:

- 78% of sales are classified as business-to-consumer, though almost all of that business is wholesale, relying on large retailers like Barnes & Noble (7% of all sales) and Waterstones to reach people. That’s clearly a liability as brick-and-mortar retail stores are mostly struggling.

- 16% of sales are business-to-business, with more than a thousand companies paying to put their logos on Moleskine products. It’s a classy gift that could grow more popular if the Moleskine brand grows in stature.

- 4% of sales occur on Moleskine’s not-very-good website, which it is planning to overhaul. Another 3% of sales occur on Amazon, which may be a more promising way to grow the online business.

- 2% of sales occur in Moleskine retail stores, which it only recently began opening: four in China and five in Italy. More are scheduled to open in New York’s Time Warner Center and Beijing’s Sanlitun Village, among other places.

Finally, Moleskine’s sales by region:

- 53% of sales are in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa, its largest market, but that’s down from 63% in 2009, reflecting expansion in other markets. Recently, sales have been struggling in Italy and Spain (of course) but doing better in France and the UK.

- 36% of sales occur in the Americas. That’s lower than one would expect for an English-language luxury brand, but the company hopes that having its own retail stores will help Moleskine the way they did Apple. A promising sign is that brand awareness of Moleskine in the United States rose from 7% in 2007, when it was really a European brand, to 56% last year, according to the company’s own research.

- 11% of sales are in the Asia Pacific region, which has seen the greatest growth since 2009. The company attributes that to expansion in Australia and South Korea. Asia is also where Moleskine charges the most for its products, according to UBS, with prices in China and Japan almost double what the company charges for the same products in Italy.