You know the face: the frowning, skeptical expression you assume unconsciously upon hearing something you disagree with. It’s not just you, nor is it just a tic of the culture in which you operate.

A team of researchers has identified a singular facial expression that appears to have evolved to show disapproval. It’s like a muscular punctuation mark universally understood across languages and cultures.

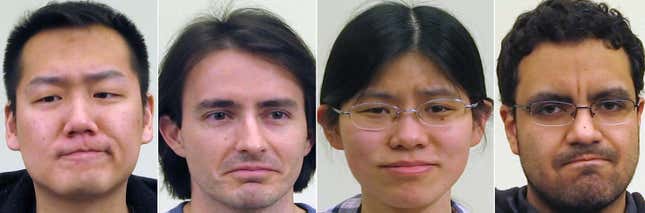

They’re calling it the “not face.”

The mild scowl marks disagreement and disapproval across speakers of languages as varied as English, Spanish, Mandarin Chinese, and American Sign Language. In ASL, the look is often substituted for the actual sign for “no” or “not.”

Please note that “not face” is different from “resting bitch face,” the internet term for a female visage that fails to assume a beatific expression when relaxed.

“To our knowledge, this is the first evidence that the facial expressions we use to communicate negative moral judgment have been compounded into a unique, universal part of language,” study author Aleix Martinez said in a statement. Martinez is a cognitive scientist and professor of electrical and computer engineering at Ohio State University.

In a study recently published in the journal Cognition, the researchers filmed and photographed 158 students speaking in their native languages. The students were asked about subjects designed to elicit unhappy responses—tuition hikes, for example.

Whether communicating in an oral language or a signed one, the students elicited time and again the same furrowed-brow expression when expressing disapproval. Furthermore, their muscles contracted into “not face” at the same rhythm as speech. The researchers believe this helps the brain interpret the expression itself as language.

The team hopes this is the start of a years-long process to catalogue human expressions, an undertaking that could help human-computer communications and enrich our understanding of where language comes from.

Finding our universal positive expressions will likely be harder, though, Martinez said in a press release. “Most expressions don’t stand out as much as the ‘not face,'” he said.