It’s an emotive and divisive debate. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) says that letting an infant child sleep in her parents’ bed “remains [the] greatest risk factor for sleep-related infant deaths.” But some health experts accuse the AAP of ignoring growing evidence which, they argue, shows that bed-sharing—if done safely—is good for the baby’s health.

In an attempt to settle the question, a group of researchers recently reviewed all of the more than 650 studies on the subject conducted between 1973 and 2015. Their report was published last month in Sleep Medicine Reviews. Its grand conclusion? There wasn’t one: The survey identified no generalizable findings.

But at least one leading researcher says he doesn’t agree. “There are many [findings] staring us right in front of our faces,” says James McKenna, head of the Mother-Baby Behavioral Sleep Laboratory at Notre Dame University. And, even if science can’t offer a firm diktat one way or the other, there are some proven good and bad practices which can help you make up your mind whether to sleep in the same bed as your baby.

Sleep tight, little one

The biggest worry about bed-sharing is Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS). Although SIDS is the catch-all term for all unexplained deaths of children under a year old, bed-sharing seems to be the biggest risk factor for those younger than three months, according to a 2014 review by Rachel Moon, the head of the AAP’s task force on SIDS. The risk is that a sleeping adult might inadvertently crush a baby, or the bedding might suffocate an infant who cannot yet move his head.

Indeed, there are some clear dangers. Parents who smoke, drink, or use drugs should not sleep next to a baby. Falling asleep with her on the sofa is also a bad idea: She could fall off your chest or nestle too closely in a corner. Other potential dangers include duvets, pillows, an extra-soft mattress, having animals in bed, or putting an infant to sleep on his tummy.

But if all these risks are countered, McKenna says, the practice is not just safe but also beneficial. He is one of the world’s leading authorities on the subject and author of Sleeping With Your Baby: A Parent’s Guide To Co-sleeping.

The benefits to co-sleeping start with the fact that very young babies are fragile. Apart from needing frequent feeding, they can’t regulate their body temperatures and breathing. McKenna’s studies show that when mother and baby sleep together, it does good things for the infant’s heart rate, blood pressure, hormonal levels, body temperature, breathing rate, and even how she absorbs calories.

Moreover, other studies show that babies who share the bed with their mothers are breastfed more than babies who don’t, probably because getting out of bed two or three times a night to breastfeed an infant in another room is exhausting. There is also some evidence (pdf) that bed-sharing at an early age can affect the kind of adult a child becomes. Those who slept with their parents early on have been shown to be happier and less anxious, have higher self-esteem, and handle stress better.

Though his own findings are preliminary and need larger follow-up studies, McKenna is therefore deeply skeptical of the AAP’s stance. “I think sleeping with the baby is normal,” he says. “This kind of caring, and the duration for which we do it, compensates for neurologically immature brains at birth.”

But if he is so confident, why do 650 studies, taken together, don’t make a clear case for bed-sharing? That could just be a problem of the way the scientific method has been applied to these studies.

The problem with the science

Viara Mileva-Seitz, of Queen’s University in Canada, one of the review paper’s co-authors, says she admires McKenna’s work, but maintains that the evidence isn’t conclusive. Almost all the studies the review looked at were designed to give clear answers only to specialists of one field. So pediatricians can confidently say that there are risks to bed-sharing, such as SIDS. Lactation consultants can confidently say that there are benefits, such as increased breastfeeding. “Our review shows that there is a need to design studies that are such that various subfields can all draw conclusions from them,” she says.

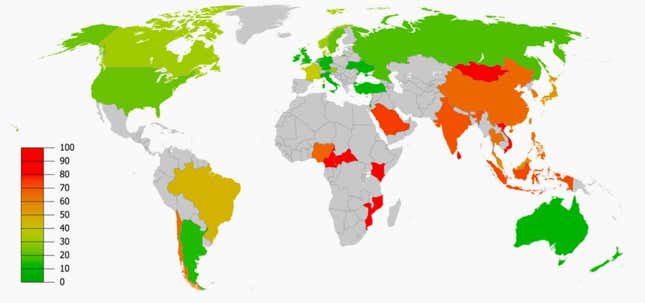

McKenna agrees that a lot of studies on bed-sharing have design flaws or biases. For instance, most studies on SIDS were conducted in Western countries where the prevailing opinion is against bed-sharing. Also, many studies ask parents of children who died of SIDS about their bed-sharing habits, but don’t ask whether they shared the bed with the baby on the night of the death.

McKenna also argues that the apparent connection between bed-sharing and SIDS, in the US at least, could be because of “structural racism.”

Probably because black families in America are disproportionately poor, McKenna says, “black women are giving birth to nearly half of all underweight or premature babies [in the US]. They are also significantly less likely to breastfeed.” Both of these increase the risk of SIDS. But—perhaps again for reasons of poverty—significantly more black women than white women share the bed with their babies. So it can look like bed-sharing is causing SIDS, when in fact, ”it’s not about bed-sharing, it’s about the lack of control over one’s life and resources,” McKenna says.

Another reason it’s hard to get a clear conclusion is that parents who bed-share can be split into two categories: “intentional,” who choose to do it, and “reactive,” who are forced into it—by not having the money to buy a baby cot, for instance. Most studies don’t take this distinction into account, but it turns out that it matters.

Those studies that did look at the distinction found that intentional bed-sharers are “more likely to bed-share all night, to endorse and be more satisfied with bed-sharing,” the reviewers write. Reactive parents, it follows, are probably less careful in their bed-sharing practices, which could mean more risk for the infants. But because most studies haven’t included this factor, it is “impossible to untangle cause-and-effect,” the reviewers write.

Finally, Mileva-Seitz says, too many researchers treat bed-sharing as a single behavior. In fact it’s a highly variable practice—in terms of everything from how often parents do it to how close to the baby they sleep—making it hard to tease out the benefits and risks.

Settle down

This is hardly the first time parents have been given conflicting advice. In 1955, Benjamin Spock, in his best-selling Baby and Child Care, recommended babies be put to sleep on their backs, but in the 1956 edition he said they should sleep on their tummies instead, to avoid choking on their own vomit. ”Tragically, none of Spock’s advice was evidence based,” writes Alice Green Callahan in The Science of Mom: A Research-Based Guide to Your Baby’s First Year.

The debate doesn’t need to be so polarized, however. Parents can learn the risks and benefits and then decide what works best for them and their baby.

The middle ground, according to McKenna, is that caregiver and child should “co-sleep.” He defines that as sleeping within sensory proximity of the baby—which could be anywhere from within hearing range to having the baby on your arm. There are even beds designed for this, called co-sleepers.

Ultimately, health advice can give you pointers, but only you can make the final decision. As long as you know the risks and benefits, you’ll make the best choice for your own particular circumstances. So get informed—and then go with your gut.