The basilica of Siponto, on a quiet road outside Manfredonia, in Italy’s Puglia region, has long been easy to miss—just another church among the thousands around the country. But these days, the 12th century structure attracts a crowd, sometimes even queues.

The reason isn’t the church in itself, though it is an authentic jewel—the last building standing of what was once an ancient Greek colony in a flourishing harbor destroyed by earthquakes (and likely tsunamis, too) in the early 13t th century.

What’s attracting the curious crowds is something that, from the highway, seems but an optical illusion.

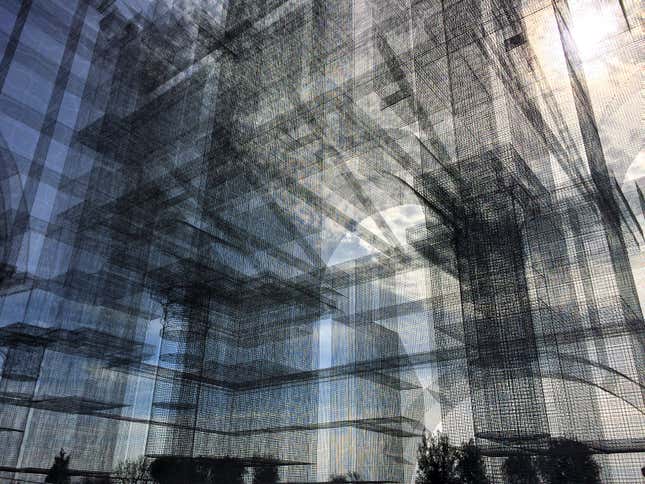

Adjoining the newly renovated basilica, standing on the ruins, towers a full blown cathedral—with its imposing arches, columns, and volumes—completely built in iron-wire mesh. It gives the appearance of a hologram, or a 3D charcoal drawing of a time that was.

The work is an installation by Milan-based Edoardo Tresoldi, a 28-years-old scenographer and sculptor, whose work with wire mesh has rapidly gained him national and international recognition, as well large commissions.

According to the artist’s studio, the structure—built with 4,500 square meters of wire mesh—is 14 meters high and weighs about seven tons, and covers a space approximately that of the original church. Meant to be a permanent companion of the historic building, the project, commissioned by the MiBAC (Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities), took five months and cost €900,000.

The installation, opened to the public on Mar. 11, has already drawn thousands of visitors in less than a month.

Tresoldi told Italian newspaper La Repubblica that the first idea was “to blend the two languages of antiquity and contemporary art,” in what he sees as an attempt to solve the tension between past, present and future that is at the core of all renovation endeavors.

Tresoldi, who has roots in street art, isn’t new to public art. In 2015, several of his wire-mesh installations and sculptures were exhibited around Italy, in the UK, and France.

From wire “people” escaping painted walls, to cages suspended midair, to large structures such as the one in Leonardo Da Vinci’s vineyard in Milan, Tresoldi’s work has an ethereal quality despite its weight, and combines at the same time a sense of freedom, and a form of captivity.