Everyone knows the story of how robots replaced humans on the factory floor. But in the broader sweep of automation versus labor, a trend with far greater significance for the middle class—in rich countries, at any rate—has been relatively overlooked: the replacement of knowledge workers with software.

One reason for the neglect is that this trend is at most thirty years old, and has become apparent in economic data only in perhaps the past ten years. The first all-in-one commercial microprocessor went on sale in 1971, and like all inventions, it took decades for it to become an ecosystem of technologies pervasive and powerful enough to have a measurable impact on the way we work.

This feature is Part II in a series on the rise of the machines. You can read Part I, on the usurpation by robots of the last of the world’s unskilled manufacturing jobs, here.

“Software is eating the world”

Sixty percent of the jobs in the US are information-processing jobs, notes Erik Brynjolfsson, co-author of a recent book about this disruption, Race Against the Machine. It’s safe to assume that almost all of these jobs are aided by machines that perform routine tasks. These machines make some workers more productive. They make others less essential.

The turn of the new millennium is when the automation of middle-class information processing tasks really got under way, according to an analysis by the Associated Press based on data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Between 2000 and 2010, the jobs of 1.1 million secretaries were eliminated, replaced by internet services that made everything from maintaining a calendar to planning trips easier than ever. In the same period, the number of telephone operators dropped by 64%, travel agents by 46% and bookkeepers by 26%. And the US was not a special case. As the AP notes, “Two-thirds of the 7.6 million middle-class jobs that vanished in Europe were the victims of technology, estimates economist Maarten Goos at Belgium’s University of Leuven.”

Economist Andrew McAfee, Brynjolfsson’s co-author, has called these displaced people “routine cognitive workers.” Technology, he says, is now smart enough to automate their often repetitive, programmatic tasks. ”We are in a desperate, serious competition with these machines,” concurs Larry Kotlikoff, a professor of economics at Boston University. “It seems like the machines are taking over all possible jobs.”

Like farming and factory work before it, the labors of the mind are being colonized by devices and systems. In the early 1800’s, nine out of ten Americans worked in agriculture—now it’s around 2%. At its peak, about a third of the US population was employed in manufacturing—now it’s less than 10%. How many decades until the figures are similar for the information-processing tasks that typify rich countries’ post-industrial economies?

Web pioneer and venture capitalist Marc Andreessen describes this process as “software is eating the world.” As he wrote in an editorial (paywall) for the Wall Street Journal, “More and more major businesses and industries are being run on software and delivered as online services—from movies to agriculture to national defense.”

The hollowing out of the middle class

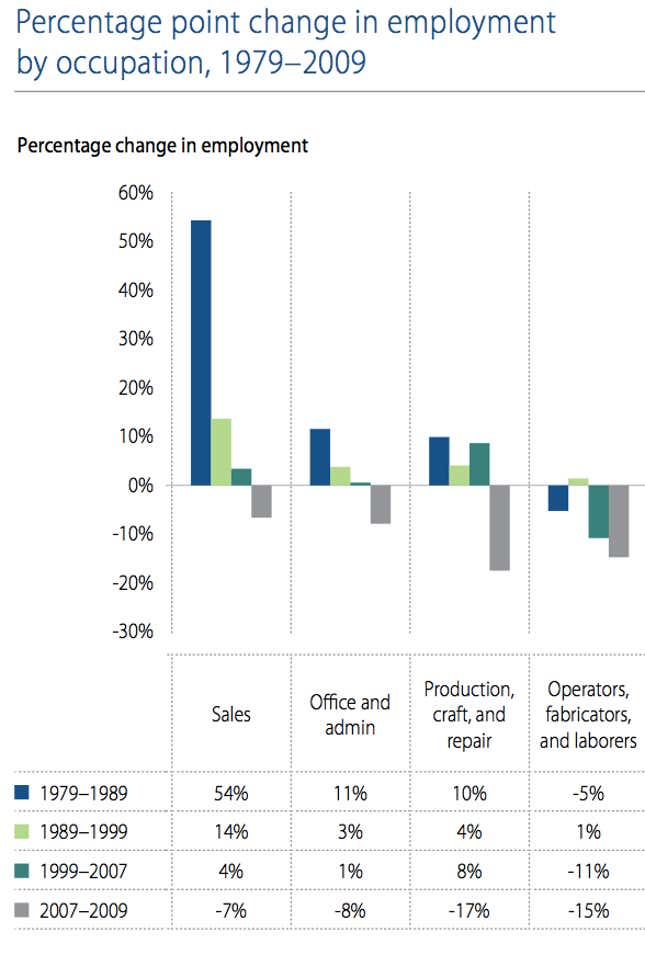

To see how the internet has disproportionately affected the jobs of people who process information, check out the gray bars dipping below the 0% line on the chart, below. (I’ve adapted this chart to show just the types of employment that lost jobs in the US during the great recession. Every other category continued to add jobs or was nearly flat.)

What’s apparent is that the same trend seen in making and processing things—represented by the “Production…” and “Operators…” categories—shows up for the routine cognitive workers in offices and, for related if not identical reasons, sales.

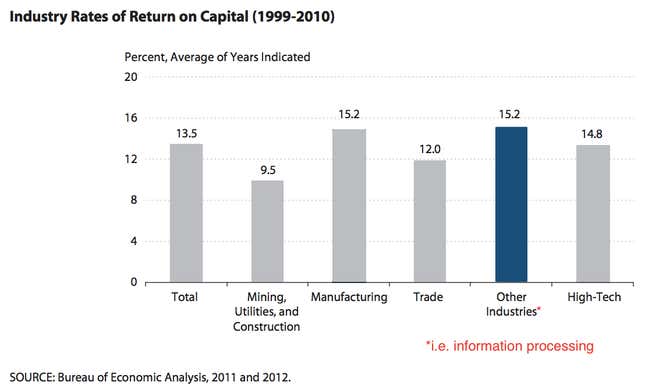

Here’s another clue about what’s been going on in the past ten years. “Return on capital” measures the return firms get when they spend money on capital goods like robots, factories, software—anything aside from people. (If this were a graph of return on people hired, it would be called “Return on labor”.)

Notice: the only industry where the return on capital is as great as manufacturing is “other industries”—a grab bag which includes all the service and information industries, as well as entertainment, health care and education. In short, you don’t have to be a tech company for investing in technology to be worthwhile.

Companies that invest in IT do better

Here’s yet a third clue about what’s going on. For many years, the question of whether or not spending on information technology (IT) made companies more productive was highly controversial. Many studies found that IT spending either had no effect on productivity or was even counter-productive. But now a clear trend is emerging. More recent studies show that IT—and the organizational changes that go with it—are doing firms, especially multinationals (pdf), a great deal of good.

One reason for the delay is that it has taken some time for companies to learn how best to use IT. Economist Carlota Perez calls this the “installation phase.” Moreover, the more recent rise of the internet has multiplied the power that IT has on its own.

In any case, if computers are the factory floor for routine cognitive workers, then when software and the internet makes some workers more productive, others are no longer needed.

Winner-take-all and the power of capital to exacerbate inequality

One thing all our machines have accomplished, and especially the internet, is the ability to reproduce and distribute good work in record time. Barring market distortions like monopolies, the best software, media, business processes and, increasingly, hardware, can be copied and sold seemingly everywhere at once. This benefits “superstars”—the most skilled engineers or content creators. And it benefits the consumer, who can expect a higher average quality of goods.

But it can also exacerbate income inequality, says Brynjolfsson. This contributes to a phenomenon called “skill-biased technological [or technical] change.” “The idea is that technology in the past 30 years has tended to favor more skilled and educated workers versus less educated workers,” says Brynjolfsson. “It has been a complement for more skilled workers. It makes their labor more valuable. But for less skilled workers, it makes them less necessary—especially those who do routine, repetitive tasks.”

The result is that, with the aid of machines, productivity increases—the overall economic pie gets bigger—but that’s small consolation if all but a few workers are getting a smaller slice. “Certainly the labor market has never been better for very highly-educated workers in the United States, and when I say never, I mean never,” MIT labor economist David Autor told American Public Media’s Marketplace.

The other winners in this scenario are anyone who owns capital. Only about half of Americans own stock at all, and as more companies are taken private or never go public, more and more of that wealth is concentrated in the hands of fewer and fewer people. As Paul Krugman wrote, “This is an old concern in economics; it’s “capital-biased technological change”, which tends to shift the distribution of income away from workers to the owners of capital.”

Unlike other technological revolutions, computers are everywhere

The ubiquity of smartphones in rich countries is just the tip of the silicon iceberg. Computers are more disruptive than, say, the looms smashed by the Luddites, because they are “general-purpose technologies” noted Peter Linert, an economist at University of Californa-Davis. Sensors, embedded systems, internet-connected devices, and an ever-expanding pool of cloud computing resources are all being put to the same use: how to figure out, in the most efficient way possible, what to do next.

“The spread of computers and the Internet will put jobs in two categories,” said Andreessen. “People who tell computers what to do, and people who are told by computers what to do.” It’s a glib remark—but increasingly true.

In a gleaming new warehouse in the old market town of Rugley, England, Amazon directs the actions of hundreds of “associates” wielding hand-held computers. These computers tell workers not only which shelf to walk to when they’re pulling goods to be shipped, but also the optimal route by which to get there. Each person’s performance is monitored, and they are given constant feedback about whether or not they are performing their job quickly enough. Their bosses can even send them text messages via their handheld computers, urging them to speed up. “You’re sort of like a robot, but in human form,” one manager at Amazon’s warehouse told the Financial Times. “It’s human automation, if you like.”

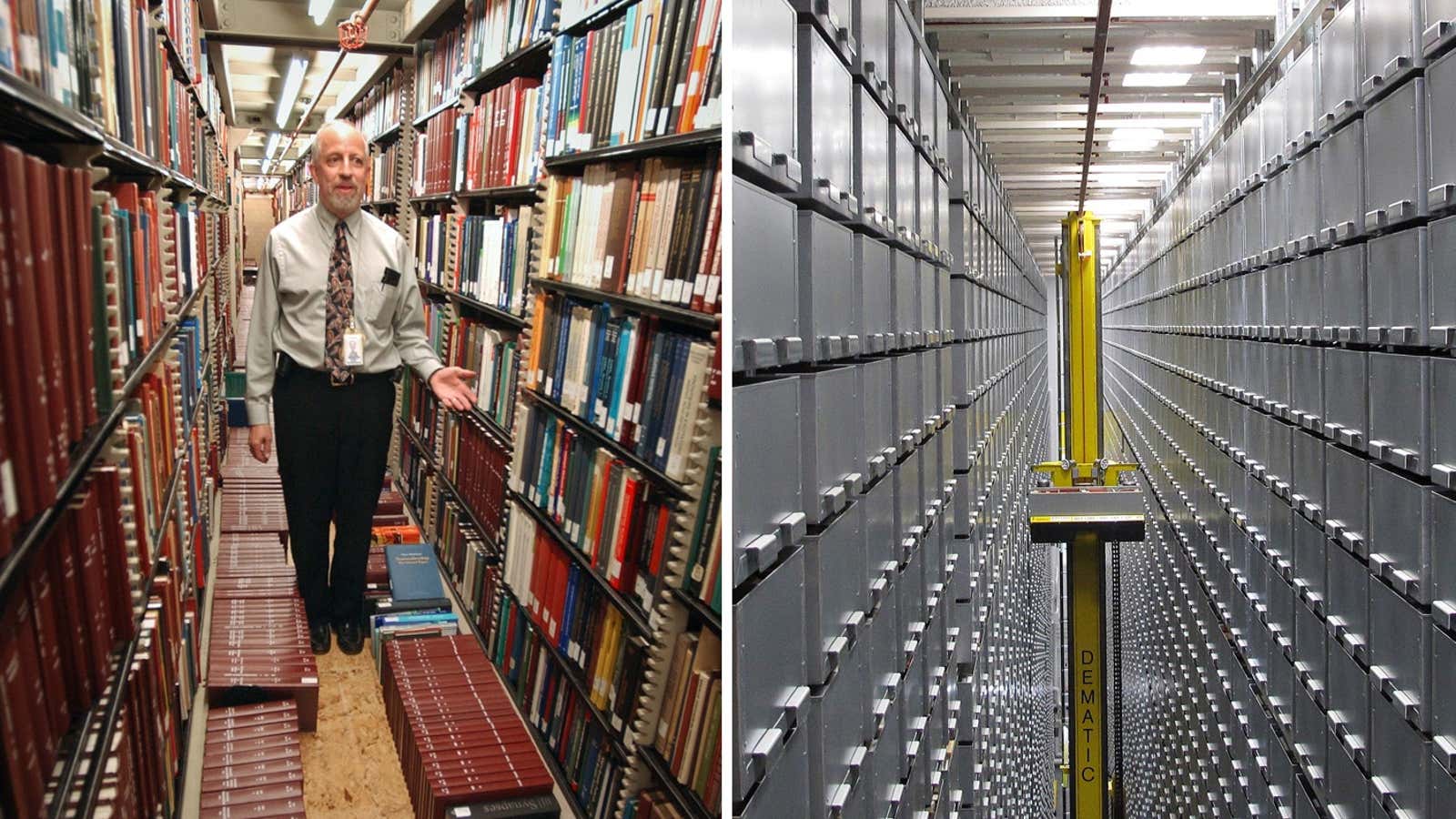

And yet despite this already high level of automation, Amazon is already working on how to eliminate the humans in its warehouses all together. In March 2009, Amazon acquired Kiva Systems, a warehouse robotics and automation company. In partnership with a company called Quiet Logistics, Kiva’s combination of mobile shelving and robots has already automated a warehouse in Andover, Massachusetts. Here’s a video showing how Kiva’s robots, which look like oversize Roombas, can store, retrieve and sort goods with minimal involvement from humans.

This time it’s faster

History is littered with technological transitions. Many of them seemed at the time to threaten mass unemployment of one type of worker or another, whether it was buggy whip makers or, more recently, travel agents. But here’s what’s different about information-processing jobs: The takeover by technology is happening much faster.

From 2000 to 2007, in the years leading up to the great recession, GDP and productivity in the US grew faster than at any point since the 1960s, but job creation did not keep pace. Brynjolfsson thinks he knows why: More and more people were doing work aided by software. And during the great recession, employment growth didn’t just slow. As we saw above, in both manufacturing and information processing, the economy shed jobs, even as employment in the service sector and professional fields remained flat.

Especially in the past ten years, economists have seen a reversal of what they call “the great compression“—that period from the second world war through the 1970s when, in the US at least, more people were crowded into the ranks of the middle class than ever before. There are many reasons why the economy has reversed this “compression,” transforming into an “hourglass economy” with many fewer workers in the middle class and more at either the high or the low end of the income spectrum. But whatever those forces, they are clearly being exacerbated by technological change.

The hourglass represents an income distribution that has been more nearly the norm for most of the history of the US. That it’s coming back should worry anyone who believes that a healthy middle class is an inevitable outcome of economic progress, a mainstay of democracy and a healthy society, or a driver of further economic development. Indeed, some have argued that as technology aids the gutting of the middle class, it destroys the very market required to sustain it—that we’ll see “less of the type of innovation we associate with Steve Jobs, and more of the type you would find at Goldman Sachs.”

Is any job safe?

Recently I sat down with the team at Betterment, a tech startup to which people have already handed over $150 million in assets. For many, that money represents a significant chunk of their savings and retirement accounts. Betterment is the sort of company that, if it does well, will someday be a canonical example of the principle that “software eats everything.” It’s an attempt replace the kind of job you might think is still beyond the reach of an algorithm: personal financial advice.

The legal field has been transformed by software too. For example, it replaced paralegals in the previously labor-intensive process of sifting through documents during the discovery phase of a lawsuit.

No one, it seems, is more aware of this phenomenon than the technologists themselves. In an interview with Pando Daily, Josh Kopelman, a venture capitalist with First Round Capital, said that even his industry is going to be eaten by software. “In fifteen years, will VCs make as much money as they do now?” he was asked. “They probably shouldn’t,” was his response.

Survival of the fittest—and the richest

Barring a civilization-ending event, technology is not going to move backward. More and more of our world will be controlled by software. It’s already become so ubiquitous that, argues one of my colleagues, it’s now ridiculous to call some firms as “tech” companies when all companies depend on it so much.

So how do we deal with this trend? The possible solutions to the problems of disruption by thinking machines are beyond the scope of this piece. As I’ve mentioned in other pieces published at Quartz, there are plenty of optimists ready to declare that the rise of the machines will ultimately enable higher standards of living, or at least forms of unemployment as foreign to us as “big data scientist” would be to a scribe of the 17th century.

But that’s only as long as you’re one of the ones telling machines what to do, not being told by them. And that will require self-teaching, creativity, entrepreneurialism and other traits that may or may not be latent in children, as well as retraining adults who aspire to middle class living. For now, sadly, your safest bet is to be a technologist and/or own capital, and use all this automation to grab a bigger-than-ever share of a pie that continues to expand.