People don’t save enough money. In most OECD countries, household saving rates (Excel) are falling but the need to save has never been greater. The more uncertain the economy, the more savings you need to protect yourself from a period of job loss, a health scare, or smaller emergencies like car repair. You also need to save for retirement especially since life expectancy has increased, few people get an employer pension anymore, and state pensions are uncertain.

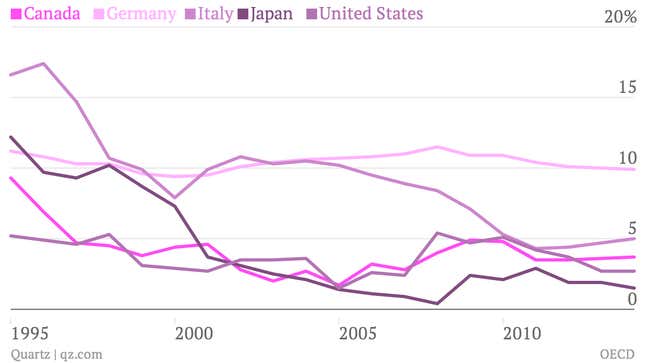

With the notable exceptions of core European countries: France, Germany, Sweden, Denmark and Norway, nearly every country’s saving rates have been falling. The saving rate went up a bit during the 2008 financial crisis, but it’s been falling back to trend since then. Despite the economic uncertainty and retirement need, the average household, in more than half of the 24 largest OECD countries, is saving less than 5% of its income.

There are different explanations for each country’s declining saving. Japan’s lower saving is often attributed to its aging population. Easy credit was often the cited reason in Anglo-Saxon countries. The saving rate normally varies with economic conditions. People tend to save more during recessions, in response to the economic uncertainty, but it’s remarkable that the trend spans many different countries and economic conditions. It seems there must be some common factor.

After the early 1980s through 2008, developed markets entered a period known as the Great Moderation, where recessions were relatively short and painless. This may have meant people didn’t feel like they had to save as much.

Another theory comes from new research by University of Chicago Booth School of Business economists Marianne Bertrand and Adair Morse. In America, they found a negative correlation between income inequality and saving. However, their theory may apply to all developed markets where income inequality widened in the last few decades (this includes Europe and Japan). Income inequality worsened in most developed markets because new technology increased the wage premium on high-skilled jobs. Bertrand and Morse found the increase in inequality accounts for a large part of the decline in saving. They speculate that middle-income Americans increased their consumption, even as their income stagnated, because they followed the consumption habits of higher income Americans, whose income did go up. New, conspicuous goods became available, which were meant for higher income consumers. But because these goods were appealing and associated with status, people of all income levels bought them, even if it meant going into debt and levering up on their housing.

Or it may also be that people have come to expect increased living standard over time even when real income doesn’t increase for most people.

The implications of a low-saving society are troubling. It means many people will not have enough for the retirement they want. It also means they are more vulnerable to economic shocks like job loss or disability, which may leave people more reliant on the state for support.

It also may have implications for policy. During the financial crisis people increased their saving rates, which resulted in lower demand for goods and services and made the recession worse. A common expansionary policy is to induce people to consume (and firms to invest) more by lowering interest rates, which reduces the return on saving. But when saving rates are already 2-3%, is that wise? In America, many people had debt going into the recession from years of consuming beyond their means. Following the crisis, credit tightened and the job outlook worsened, and people had little choice but to repair their balance sheets. Keeping interest rates low did not have the same effect it normally does. There’s only so much you can do to juice consumption when people are barely saving to begin with. A low-rate policy can even be self-defeating. If a large part of your population is nearing retirement and invested in low-risk assets, the low interest rates can have a wealth effect, which makes people feel poorer so they decrease their consumption.

Because a high saving rate is associated with recessions and low demand, it’s often considered a problem that needs to be fixed—so policy aims to expand credit and keep interest rates low. But there exists an optimal saving rate. It’s hard to say exactly where that is; it depends on the age of your population and how mature your market is. But for most countries, smaller than 5% is too low. In the long run, more saving leads to more growth. Saving fuels investment, which makes it possible for firms to expand and grow. Saving also empowers people to be more entrepreneurial—personal savings is often the source of seed funding for new entrepreneurs. A consumption-led growth policy may be appealing in the short term, but for many reasons policy should do more to reward rather than punish savers.