Learning that you have cancer is shocking. During treatment, the last thing you want to consider is having cancer ever again.

But for many of us who’ve been diagnosed, especially at a young age, it’s a prospect we must confront.

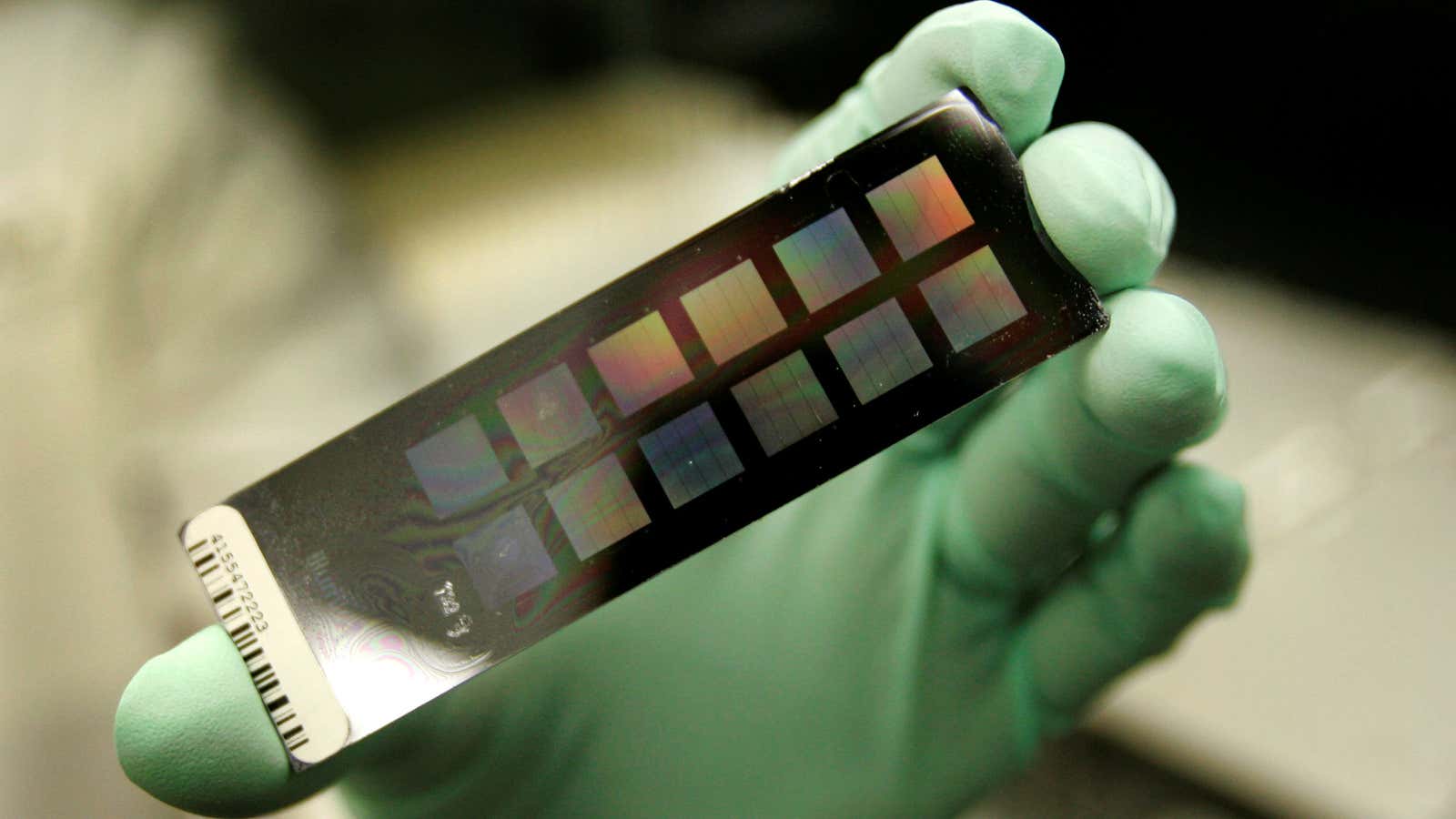

When I was diagnosed with breast cancer two years ago at age 31, genetic testing was part of an initial battery of tests. If I was a carrier of the BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation, it would mean that a double mastectomy was without a doubt my course of treatment. Having those mutations predisposes women to developing breast cancer at a young age, as well as in both breasts. Despite what many people think, breast cancer is typically not hereditary, but mutations like these account for many of the familial cases. Only an estimated 7% of breast cancers are caused by mutations of this gene.

But here’s the rub: carrying the BRCA gene mutations put your likelihood of developing ovarian cancer up to 40% (the probability is higher with BRCA1 than BRCA2). Many of my friends who have the mutation have been advised to have their ovaries removed by the age of 40 as a preventative measure. In some cases, BRCA mutations are also linked to a higher likelihood of pancreatic cancer and melanoma.

I tested negative for BRCA, but there are other genetic mutations related to breast cancer: p53, ATM, PALB, and CHEK2.

My insurance required that I receive genetic counseling with my testing. The genetic testing company advised that I be tested for p53, or Li-Fraumeni syndrome, which is a rare disorder linked to breast cancer, sarcoma, and leukemia.

This, I found terrifying. I could barely wrap my head around the fact that I had one cancer let alone the prospect of having another.

I tested negative for p53.

When I met with a woman who was diagnosed with breast cancer in her thirties, she encouraged me to get my entire panel of genetic testing done as she had. I couldn’t think of anything worse than finding out that I had a higher likelihood for developing another cancer. And my oncologist wasn’t advising it. A recent study in the American Journal of Human Genetics found that testing beyond breast or ovarian cancer-specific genes has no clinical benefit. For patients with mutations in the ATM or CHEK2 genes, there are not yet guidelines on what kind of care to provide.

More information doesn’t necessarily mean more knowledge. As I went through treatment, I learned about the risks of chemotherapy: I could feel nauseous or, in a decade, I might develop leukemia; from radiation, I could experience skin discoloration or get heart disease. I was at risk for a range of side effects from the minor to the catastrophic, and the doctors had no idea who would experience what. They also couldn’t tell me why I developed cancer in the first place or whether it would return.

Being treated for cancer is an exercise in learning how little doctors know about cancer.

Recently, Quartz reporter Katherine Foley interviewed Lisa Sanders, a doctor of internal medicine who served as inspiration for the TV show House. Sanders said:

We like to give the impression that if you have questions, we have answers. But actually, there’s a lot of wiggle room in that. … If you put on one plate all the stuff we know, and on another all the stuff we know we don’t know … I think it’s about equal. And I think everyone in medicine recognizes that there’s a huge dollop of stuff we have no idea about.

Just this year I found out that friend of a friend had developed a second breast cancer in the opposite breast. She discovered that she had a mutation in the ATM gene. I asked my doctor if I should be tested for it. Or what about colon cancer, which my maternal grandfather had in the 1960s?

She told me not to worry about it, and I won’t. Tests and probabilities are abstract; they can’t prepare you for the trauma of a life-threatening illness. The only antidote I know is to live.