To transport wine and olive oil from Madrid to Yiwu, China, via the ambitious “One Belt, One Road” project, Spanish producers need to wrap bottles in thermal blankets to protect them from the cold of the Russian tundra—or else their products will freeze and explode.

“The train containers aren’t heated or refrigerated,” César Jiménez, from Kerry Logistics in Madrid, explained to Quartz.

Even then, the thermal blankets can only keep the temperature of products within 10 degrees Celsius of the outside cold or heat, Jiménez said. Because most of the cargo coming from Spain to China is food and beverages, which are sensitive to temperature changes, that means the rail line is only an option in the mild weather of spring and autumn.

And that’s providing the exporting companies can pay the €2,000 price per container—far more than what it costs to ship products by sea.

In November 2014, China expanded an old cargo train line that linked Germany to China to transport car components to Spain, creating a 13,000 km railway with the aim of increasing exports from China and bringing Spanish food to Chinese consumers. The trip takes 18 days, crossing France, Germany, Poland, Belarus, Russia, and Kazakhstan.

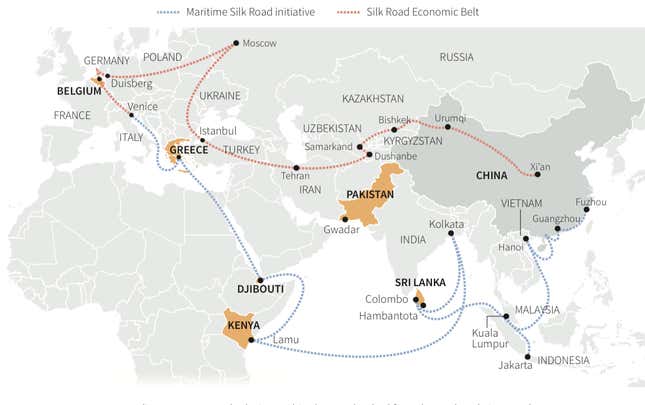

It is part of the massive “One Belt, One Road” commercial and military initiative launched by China in late 2013. OBOR, as it is known, includes a maritime route that would link Asia with East Africa and Europe through the Suez Canal; and an inland route following the old Silk Road that would cross Central Asia to Europe.

But Spanish producers aren’t embracing it. “It’s expensive—the train may be double the price—and it is not suitable for the extreme weather in summer or winter,” Jiménez said.

Only eight trains have traveled east from Madrid from the time the line started until March 2016, while 39 have arrived from China, according to Spanish newspaper El Pais. (Repeated calls to confirm these numbers made to Timex Industrial Investment in Yiwu, which manages the train, weren’t answered.) Spanish producers who are using the train told the paper it was because their products would get free advertising on Chinese state television if they did.

Spain’s experience highlights some of the on-the-ground flaws of the massive OBOR project, which China is relying on to help keep its economy growing, but has billed as a mutually beneficial development project. OBOR provides “wide and open avenues for us all,” one of the ruling Communist Party’s top officials said today (May 18) in Hong Kong.

Some analysts say one of the main reasons China launched the OBOR initiative is to try to find new markets for its domestic overproduction. The project will “build infrastructure in other countries to give Chinese steel and construction materials a commercial use,” explained Roland Vogt, a professor in the European Studies Program at the University of Hong Kong.

The overcapacity problem could be solved by closing down firms in China, but that would eliminate much-needed jobs.

Another major purpose of OBOR is geopolitical, said Chenggang Xu, a professor of economic development at the University of Hong Kong. “For example, some of the key sea routes are seen as controlled by the Americans. If there was a war and a blockade, China would have to rely on the trains,” he said.

China is financing several railway projects along Southeast Asia and Eastern Europe, including a high-speed train from Belgrade to Budapest built by a consortium led by the Chinese Railway Group, on the stipulation that these European countries use products and equipment made in China.

The problem is, there’s really no need to use trains to increase commerce between Europe and China. Sea cargo transportation is much cheaper, and companies already rely on it. More than 19,000 containers can be placed on a single cargo ship, and they only take 30 days from Europe to reach China.

The railway’s cost is only getting more prohibitive as sea shipping rates go down, thanks to an ongoing glut of shipping capacity.

In fact, shipping rates have fallen this year to historic lows, because of a glut of ships.

Yes, the railway is faster than a shipping container, but is also riskier because it goes through a few unstable countries and can be interrupted by extreme weather, terrorist attacks, and politics, Xu said. “The Russian government is not very happy about the Central Asian link,” he added. “In their view they should dominate Central Asia.”

China is trying to justify its domestic overproduction by creating the “One Belt, One Road,” and framing it as a business strategy that is also beneficial for other nations—but the actual benefit for some trading partners and the long-term global economy is still to be seen.