Nearly a year after promising a long-overdue update to the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), the White House has set a new salary threshold that will make an additional 4.2 million American workers eligible for overtime pay.

Starting Dec. 1, employers with annual revenue above $500,000 must pay time and a half for extra hours put in by full-time, salaried employees making less than $47,476, or about $913 a week. That’s more than double the current $23,660 threshold, which was last updated over a decade ago, and it means that the percentage of salaried US workers eligible for overtime after 40 hours will jump from 7% to 35%, according to US labor secretary Thomas Perez. (In 1975, it was 62%.)

Businesses have one obvious reason to be wary: The Labor Department estimates the rule could yield an additional $12 billion in worker pay over the next decade, and pegs average employer costs at between $239.6 and $255.3 million per year.

But resistance may also have to do with the specter of overtime lawsuits.

The average wage for a US non-farm employee is $48,320, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, just $844 over the new threshold. That means many employers across many industries are staring down a six-month deadline to FLSA compliance.

Preparing for the new rule means assessing newly eligible employees and comparing the cost of their potential overtime to the potential loss of their “overtime” productivity, or to the cost of simply giving them a base salary above the threshold. It’s tedious but worthwhile due diligence: The number of FLSA cases filed in US district courts has already skyrocketed, to 8,781 in 2015 from 4,039 a decade earlier. Overall, the FLSA caseload has increased by more than 400% since 1996.

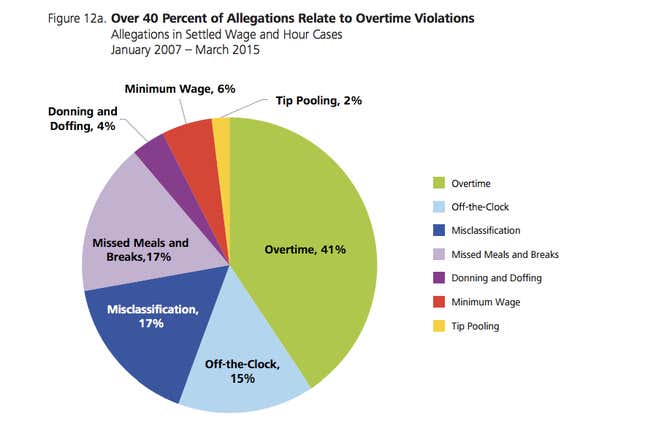

The average cost of settling a wage and hours case has actually fallen in recent years, to $5.3 million in 2014, according to NERA Economic Consulting. But that price tag is hardly insignificant, and employers have paid out an aggregate $3.6 billion to settle such cases since January 2007. A majority of those lawsuits relate to overtime. The industries most commonly affected are financial services/insurance, retail, and food and food services, which also are the industries most likely to be affected by the new FLSA threshold.

There is an argument to be made that a law enforcing the 40-hour workweek could be good for employees. A study published by the National Bureau of Economic Research in 2014 examined worker happiness in Japan and South Korea, each of which instituted a 40-hour workweek by imposing strict overtime regulations. Researchers found significant increases in “life satisfaction” in both countries after the overtime laws took effect.

But the worker happiness argument can seem a bit Pollyanna-ish when presented to a nation of workers still skittish from the financial crisis and recession. It may be that very anxiety around employment that has led an increasing number of workers to seek out information on their overtime rights, spurring an increase in FLSA cases. The latest announcement from the Obama administration only stands to boost that awareness.