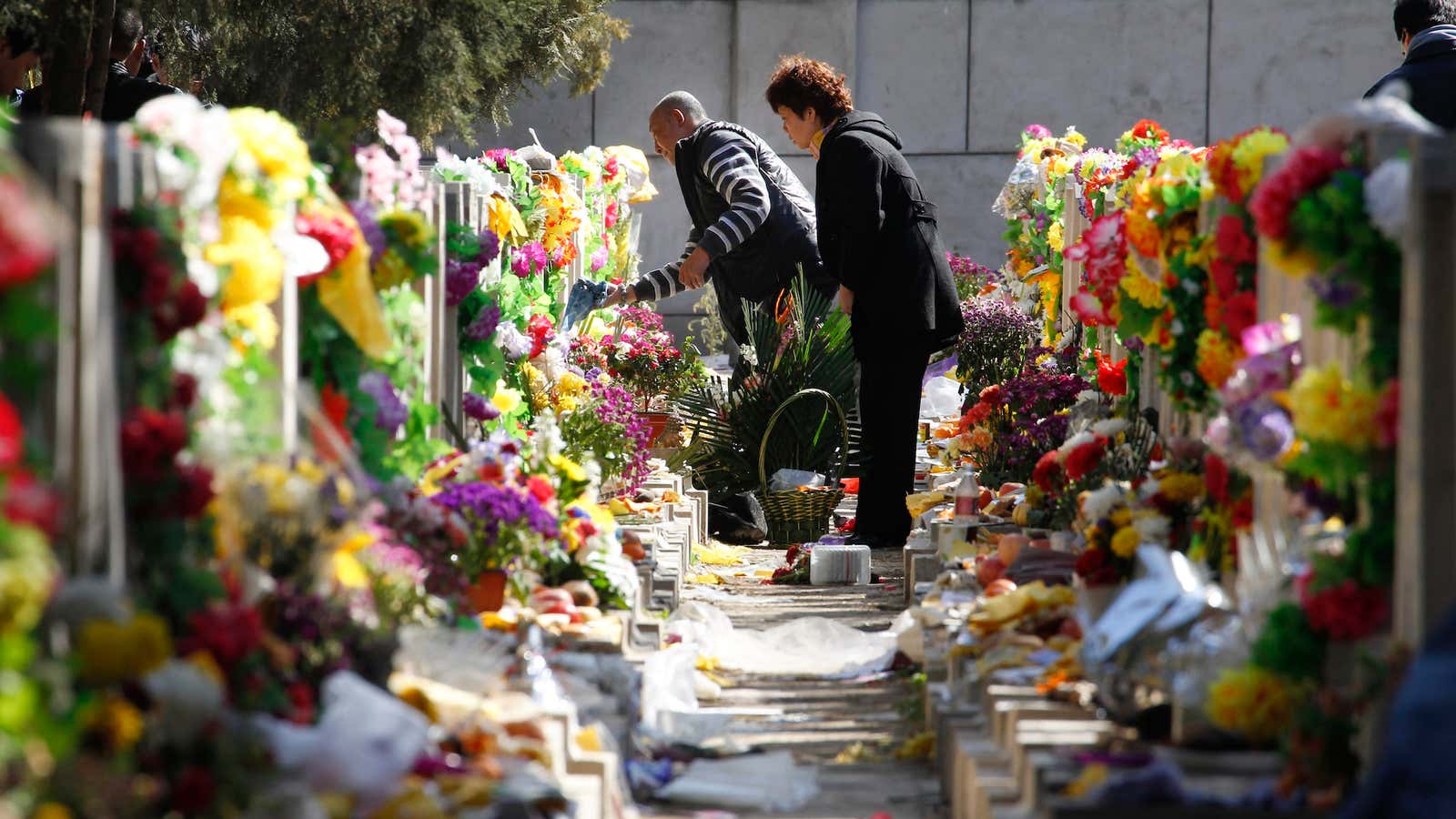

Qingming jie or Tomb Sweeping Day is a Chinese counterpart to Mexico’s Day of the Dead, when people honor their ancestors by visiting their graves and leaving them food and gifts to use in the afterlife. But Chinese city governments are using this more than 2,500-year-old tradition in a subtle campaign to overturn traditional burial customs, and thereby deal with a rather more earthly problem: There just isn’t enough space to bury people.

The festival falls on the 15th day after the spring equinox—this year, it’s on April 4. The product of a mix of ancestor worship and Confucian ideals of pre-Communist China, it was suppressed during the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s but reinstated in 2008 as a way to bolster a sense of Chinese national identity. (Confucianism, also formerly vilified, has been revived in much the same way.) And in yet another example of how China’s leaders try to erase or repurpose old traditions to fit a practical agenda, cities along China’s eastern coast are now using the Qingming holiday as a day for holding mass burials at sea.

With 9 million people to bury every year, and more of them in cities than ever before, space for cemeteries is at a premium, with the price of grave plots in some areas higher than that of apartments. (Authorities have had to clamp down on graveyard speculation.) Cities like Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Jiaxing in Zhejiang province are practically paying residents to forgo regular burials of their loved ones, often covering the cost of transportation, doing sea burials for free, and offering subsidies of up to 5,000 yuan ($800)

And those efforts are ramping up. Shanghai recently increased its subsidy to residents fivefold and added another ship to its sea burial fleet. The government in Guangzhou, an economic powerhouse in the south, said it aims to “deepen reform, save land, and change social traditions,” according to the China Daily.

The campaign could be successful. Given soaring prices for funeral plots, more people are willing to go for sea burials. In Shanghai, where one-square-meter (10 sq feet) funeral plots can cost up to 24,000 yuan, the number of seafaring burials is slowly but steadily increasing and makes up 1.5% of roughly 110,000 annual burials.

Moreover, depositing your loved one’s remains at sea is a good way to make sure they don’t get stolen. Rural families in the north, where growing numbers of men are ending up unmarried due to the country’s skewed sex ratio, often seek arranged marriages in the afterlife for deceased family members. These “ghost marriages” are feeding an industry of corpse stealing. Earlier this month, four men in Shanxi province were sentenced to jail for digging up and stealing female corpses that they sold for 24,000 yuan.

It’s not the first time the government has tried to change burial habits. Mao Zedong banned traditional burials and said all deceased had to be cremated. (Then again, Mao himself ended up being embalmed and interred in a mausoleum in Beijing.) The cremation policy was loosened somewhat in the 1980s. So far there’s no talk of mandating sea burials in the same way. In today’s somewhat freer China, gradual adoption is more likely.