This week, the world is mourning the loss of Muhammad Ali–a sports legend, global cultural icon, and, notably, a radical Muslim.

Today, the term “radical” has only negative connotations when used to describe Muslims. And yet, throughout his life, Ali consistently opposed militant Muslims whom he felt maligned and misrepresented the true teachings of Islam with their violent methods, from the perpetrators of the Iranian hostage crisis to the shooters behind the San Bernardino attacks. Despite his fierce opposition to the policies of the US government and his commitment to black liberation, Ali remained committed to the radical power of peaceful dissent. Defining a radical Muslim as someone who condones or carries out terrorism is not only narrow-minded, it has actually hurt our efforts to combat terror.

Ali, who died on June 3 after a 32-year battle with Parkinson’s, is being memorialized by many as the embodiment of patriotic dissent. And yet, today such dissent is becoming more difficult and more difficult—even dangerous. Consider the lynching charge leveled against a Black Lives Matter leader in California or New York governor Andrew Cuomo’s executive order effectively blacklisting pro-Palestinian advocates who support anti-Israel boycotts in his state.

When Ali refused to serve America as a Muslim conscientious objector during the Vietnam War, he was nearly imprisoned, lost his title, was banned from competing, and became one of the most hated figures in the country. And yet today, we look back on Ali’s radical commitment to peace as courageous, heroic, even quintessentially American. But why don’t we also consider Ali’s courage, his opposition to racism, his commitment to peace as Islamic?

While not necessarily reflective of the average textbook biography, Muhammad Ali represents an alternative, and, yes, radical strain of Islamic thought and social justice activism. His approach traces its roots to Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad rather than Egyptian political radical Sayyid Qutb, Osama bin Laden, or ISIL leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. Attracted to the Nation of Islam’s critique of white supremacy, as well as its theology of black liberation and black empowerment, the boxer announced his conversion and took the name Cassius X on February 26, 1964–the day after winning world heavyweight championship. Muslims in the Nation of Islam changed their “slave names” to “X” to mark their unknown heritage: the intellectual, spiritual, and familial genealogies lost in the ravages of slavery. The symbolic change also highlights the moral uplift of the Nation of Islam principles, which aims to help converts overcome everything from alcoholism to a life of crime.

At the time, his conversion was regarded with deep suspicion and indeed disgust by those who mischaracterized the Nation of Islam as a cult or even as a hate group. Recognizing the genius of the new convert, however, Elijah Muhammad gave him the new name Muhammad Ali.

Like Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali ultimately left the Nation of Islam and become a Sunni Muslim. But it would be a mistake to understand Ali’s religious evolution as a slow de-politicization or as a process of “transcending race.” After the death of Elijah Muhammad in 1975, the Nation of Islam leadership splintered. The majority of members followed Elijah’s son, W.D. Muhammad, who had long been advocating for a move towards Sunni Islam. A smaller group led by Louis Farrakhan remained committed to the original theology. Too often, Muhammad Ali’s conversion to Sunni Islam is used to suggest his views on race changed to become more palatable for white Americans.

While Parkinson’s may have quieted Ali, his commitment to social justice and black liberation has remained consistent over his lifetime, from the press conference in 1964 in which he announced, “I’m not an American; I’m a black man!” to his 2014 Tweet in support of Trayvon Martin and the Black Lives Matter movement.

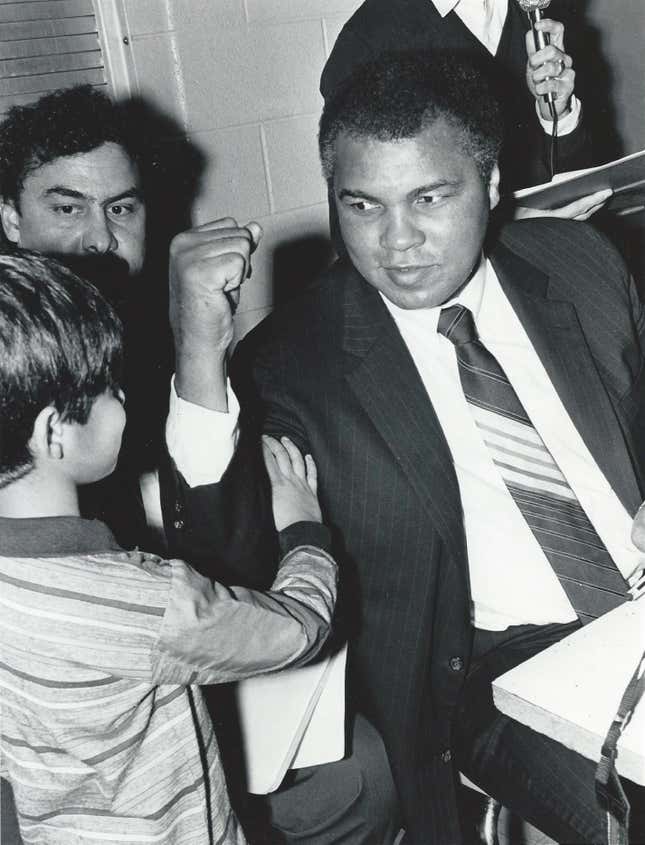

One of the extraordinary things about the People’s Champ is how accessible he was, even at his peak. When I was a kid, Ali visited our Sunday school in our Sunni Muslim community of Indian and Pakistani immigrants outside of Detroit, Michigan. Growing up, discussions of Ali’s fights and politics were treated with a reverence bordering on the religious. My little brother got in the autograph line so many times that Ali eventually recognized him and playfully let him feel his biceps, a moment captured by a local reporter. We chased the limo out of the parking lot. It paused for a moment in front of the dumpster so that Ali could greet an elderly black janitor who was there smoking, waiting patiently. Ali never forgot about those who might not have the privilege to wait in line for his autograph.

Decades later, I do not recall much from the dry Sunday school lessons. But Ali’s example, his courage and his generosity of spirit, still inspires me as a Muslim.

And so even as we mourn Ali this week, we should also celebrate him. Louisville, the city that once officially renounced him for his politics, now boasts a main street named after him. In a few days, he will be buried there, and the services will be officiated by a courageous and learned African American Sunni religious leader, Imam Zaid Shakir of Zaytuna College–a friend to the Ali family and a life-long social justice advocate in his own right. Ali’s legacy as a black radical is simultaneously political, liberating, and Islamic. We must not bury it.