Is it racist to hate Mexicans? Last week (June 3), MSNBC’s Mark Halperin insisted on Bloomberg’s With All Due Respect that it is not, because, in his opinion “Mexico is not a race.”

Halperin was responding to Donald Trump’s (who else) claims that judge Gonzalo Paul Curiel’s Mexican heritage made him unfit to preside over a court case involving allegations of fraud at Trump University. Trump claimed Curiel, who was born in the United States, was inherently opposed to Trump’s anti-immigration stance and therefore biased. Halperin reluctantly agreed that the attacks on Curiel were “racially tinged.” But, he insisted, “Mexico is not—Mexican is not a race.”

In the United States, racism is most often discussed in the context of prejudice against black people. As a result, people like Halperin often resist the application of the term “racism” to other communities. For example, when you talk about racism against Muslims, Twitter “eggs” will line up to inform you that Muslim is not a race. Muslim is a religion. Hating Muslims, therefore, cannot be racism.

These arguments are often willfully disingenuous. But they’re also based on a logical fallacy. The argument that Mexican is not a race assumes that race is a real thing. Humans, Halperin’s comments suggest, are coherently, authentically separable into groups on the basis of something that can recognizably be called “race.” Only when you criticize one of those “real” racial groups are you guilty of racism.

But in reality, those real racial groups don’t exist. Race is not a scientific designation. Eugenics, phrenology, The Bell Curve, and all the other pseudoscientific branches of race science have long since been debunked. Scientifically, humans are all one race just as we’re a single species. Genetic variation among, say, Asians, is significantly greater than genetic variation between Asians and Caucasians. For that matter, even straightforward observation can tell you that divisions by race are arbitrary. There are plenty of black people with lighter skin color than that of people the Census might officially consider white.

Racial divisions aren’t scientific; they’re ad hoc cultural groupings. And that means that race can actually be defined in a whole host of ways. Yes, you can organize people on the basis of their skin tone, if you want. You can also define race in terms of ethnicity, or nationality, or language, or religion.

Most often, race is defined using some overlapping subset of all of these methods. For hundreds of years the English have racialized the Irish on the basis of their ethnicity, their nationality, their Catholic religion, and their language—all of which were subsumed in a single racist vision of Irish people as subhuman. Adolph Hitler defined Jews through both religion and ethnicity; The fact that religion is not a race didn’t stop the Holocaust.. Genocide scholar Robert Cribb argues that even political groups or affiliations can be treated as racial identities—as communists were by Indonesian president Suharto and his troops during the 1965-66 Indonesian genocide.

The United States itself has a long history of conflating national and racial identities. “Irish,” “Italian,” “Chinese,” “Japanese,” “German,” and yes, “Mexican,” have all, at one time or another, been used as, or replaced with, racial slurs in America. When Trump slurs Mexicans, he’s using established racist categories.

But he’s also working to create racial categories. Trump, as a presidential candidate, has worked hard this election cycle to racialize, or re-racialize, groups that aren’t usually, or have largely ceased to be, the target of racist invective. Light-skinned Cuban Americans like Ted Cruz are not generally the target of racism—yet Trump used not-especially-coded attacks against his one-time rival, pillorying him as un-American and spinning wild conspiracy theories based on his Cuban identity. Racism against white Jews is strongly disavowed by both Democrats and Republicans—but when Trump supporters launched anti-Semitic attacks against a reporter Trump disliked, the candidate just shrugged.

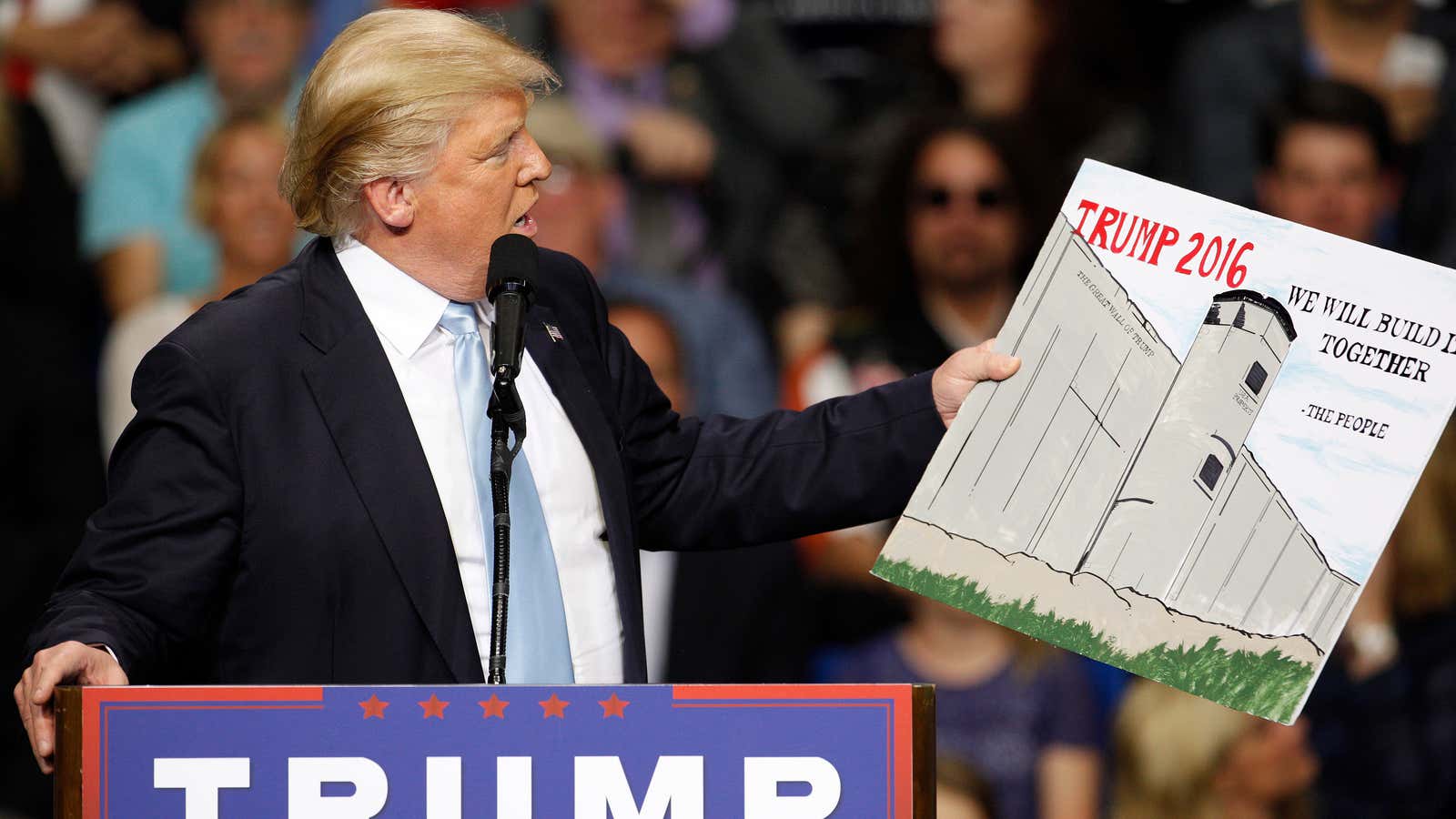

Racism doesn’t mean hatred of a particular race, because there is no such thing as a particular race of humans. Instead, racism is the process whereby a heterogeneous group of people is defined as a homogenous group in order to single them out for specific hate. When Trump points to people of Mexican descent and says that they are criminals and un-American, that they are biased and can’t be trusted, he is, deliberately working to turn Mexican into a race. He is saying, over and over, that Mexicans are different and lesser. His remarks are not just racially tinged. They are designed to stoke racism, and justify discrimination.

Throughout this election, Trump has sought to gain political advantage by defining himself, and his supporters, as virtuous Americans who have been pushed to the margins by those less virtuous and less American. Racism—which is flexible and adaptable precisely because race has no real referent—is his go-to strategy. Mexican isn’t a race, because there is no “race.” But that fact won’t stop fascists—or extremists from any ideology for that matter—from hating.