We take a closer look at the iPhone’s declining numbers, what caused them, and what they could mean for the product’s future.

Surprise, the iPhone tree won’t grow to the sky.

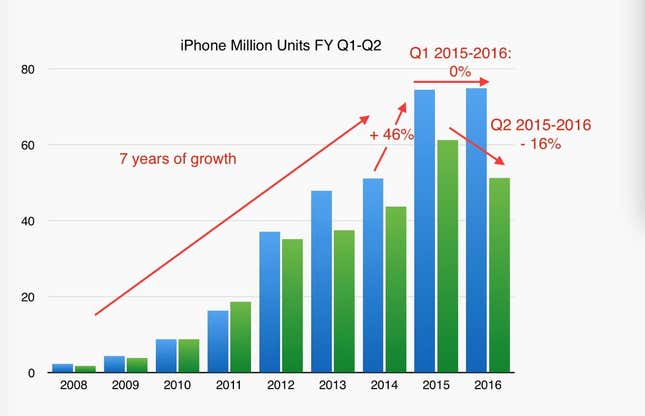

From 2.3 million units in the 2007 Holidays quarter to 74.5 million units seven years later, the iPhone experienced epoch-making growth. But then it stalled in the first quarter of (fiscal) 2016 (0%) and dipped brutally (-16%) in the following quarter:

(Confusingly, Apple’s fiscal year starts with the last quarter of the previous calendar year. Thus, Q1 Fiscal 2016 is actually the last quarter of 2015. Ah well…)

We can jump over the torrent of “I told you so”s and instead attempt to diagnose the ailment, and form a prognosis for the patient.

The first element of note is the anomalous 46% growth from Q1 2014 to Q1 2015. In absolute numbers, moving from 51 million to 74.5 million units challenges our intuitions about large quantities. Often and improperly referred to as “the law of large numbers,” experience tells us 100% growth is much easier increasing from 1 to 2 than from 40 million to 80 million. So, where did that 46% growth come from, on top of an already-very-large 51 million iPhone volume?

The simplest answer lies in an “Apple finally…” explanation: After letting Samsung and others take the lead in large screen smartphones (5.5” or larger phablets), Apple finally introduced its own large iPhone 6 Plus in Sept. 2014. Bottled-up demand manifested itself and led to a historic Christmas quarter (Q1 Fiscal 2015). Apple execs hastened to declare the numbers a “tough compare,” by which they meant that future results might pale in comparison and, indeed, when the Q1 2016 numbers were released, the pallor was conspicuous: zero year-to-year growth.

The “unbottling” of demand for large screens may explain the iPhone’s historic 46% rise in 2014, but it can’t be the entire reason for a complete stall a year later.

In general, I’m wary of multiple explanations, they often amount to an admission of failure in building a solid causal link. But in this case, I think we’re seeing a confluence of two factors.

First, the iPhone 6S vintage wasn’t different enough from the iPhone 6. Live Photos, Force Touch, and a faster processor are nice improvements, but not enough to motivate new buyers or trigger upgrades and generate growth.

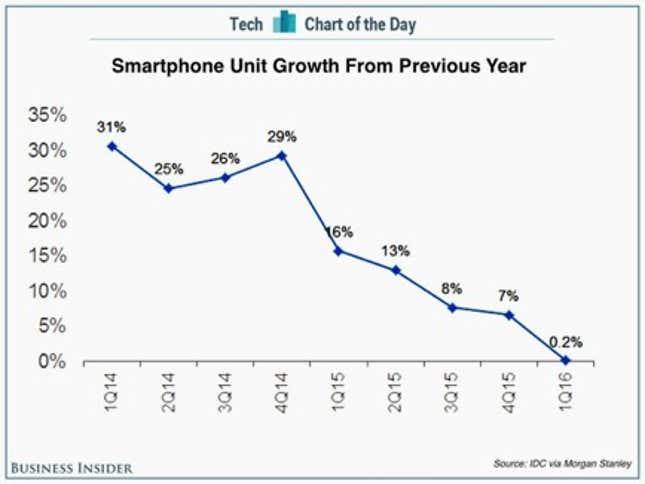

Second, the entire smartphone market—including China—seems to have stalled:

The market slowdown plus the lack of wow factor in the iPhone 6S might explain the 16% year-to-year decrease in Q2 Fiscal 2016 (which ended in March).

Is this the end of the era of Apple exceptionalism? In a no-growth or slow-growth market will the company’s star product fall prey to legions of inexpensive but increasingly capable Android devices? Does the iPhone—and the smartphone in general—so fully satisfy our needs that there’s no more pent up demand to unbottle? To put the question in more academic terms: Are smartphones already over-serving customers?

We’ve seen this in other industries: Devoid of meaningful new features and with no new vein of customers to tap, decadent versions of a once remarkable product devolve to cosmetic changes and laundry detergent-style “New And Improved!” marketing campaigns. This is one possible interpretation for announcements such as bendable phones and other gadgety variations.

Let’s assume for a moment that smartphones have reached full adulthood, that the market in the developed world is close to saturation, and that emerging markets can only support the dissemination of entry-level, sub-$50 Android devices. What does this mean for Apple?

The conventional wisdom is that low-end smartphones will grow in power and ultimately kill expensive luxury devices such as the iPhone. This is the Netbook argument from a decade ago: Low-cost, “standard” (meaning Windows) devices are going to lead the proprietary Macintosh to its preordained grave.

It never happened, of course. Cheap Netbooks were a safe and inexpensive way for newcomers to enter the market, but the Macintosh line prospered as an “aspirational” product. Consider your first car: No doubt it was purchased on the basis of limited financial resources while a more comfortable vehicle beckoned, awaiting your professional progress. Similarly, the Mac took market share away from Windows PCs as users graduated to higher levels of sophistication.

The same thing may happen with smartphones. The rise of rock-bottom priced smartphones could act as a gateway to the iPhone. Emerging markets will feed this growth with new, aspiring customers. As the middle classes grow in developing nations, the iPhone could become an affordable luxury, much as it has in the first world.

Furthermore, as the smartphone market matures and inevitably flattens, other aspects of a product’s ecosystem will become increasingly important. This is where Apple’s ever-improving Services offerings will continue to make a difference, particularly when compared to the company’s competitors whose reliance on an increasingly fragmented Android macrocosm isn’t likely to lead to a polished, reliable experience.

Just as important, perhaps the smartphone isn’t played out as a tech device—it might surprise us. In at least one smartphone use, photography, we’re likely to see continued efforts that aren’t mere cosmetic changes—improvements such as dual lenses, one for wide angle shots and another for distant subjects. As we now know, smartphones have not only taken over amateur photography and video, they’re making inroads in some professional uses, as well. The potential has barely been tapped.

The iPhone go-go years are probably behind us. We’re not likely to see 46% year-to-year growth again, but the iPhone will surely not go the way of the iPod. Apple’s “pocket computer” is more likely to follow the trajectory of the Macintosh: It will continue to take a significant but slowly growing share of the market, while pocketing a large share of the profits.

This post originally appeared at Monday Note.