Whaling was a big business in the 19th century, but, thankfully for the whales, it’s now more or less a historical footnote.

A pair of Harvard Business School professors thinks there’s still value, though, in teaching students about the defunct industry that peaked in 1858. Thales Teixeira and David Bell recently authored a case—the standard HBS teaching tool, which lays out a business problem for a class to discuss—that centers on who owns the rights to a whale’s oil after multiple ships harpoon the animal.

The issues the case presents, Teixeira says, has direct bearing on the online advertising industry, where it’s often hard to know which ad to credit when consumers make a purchase.

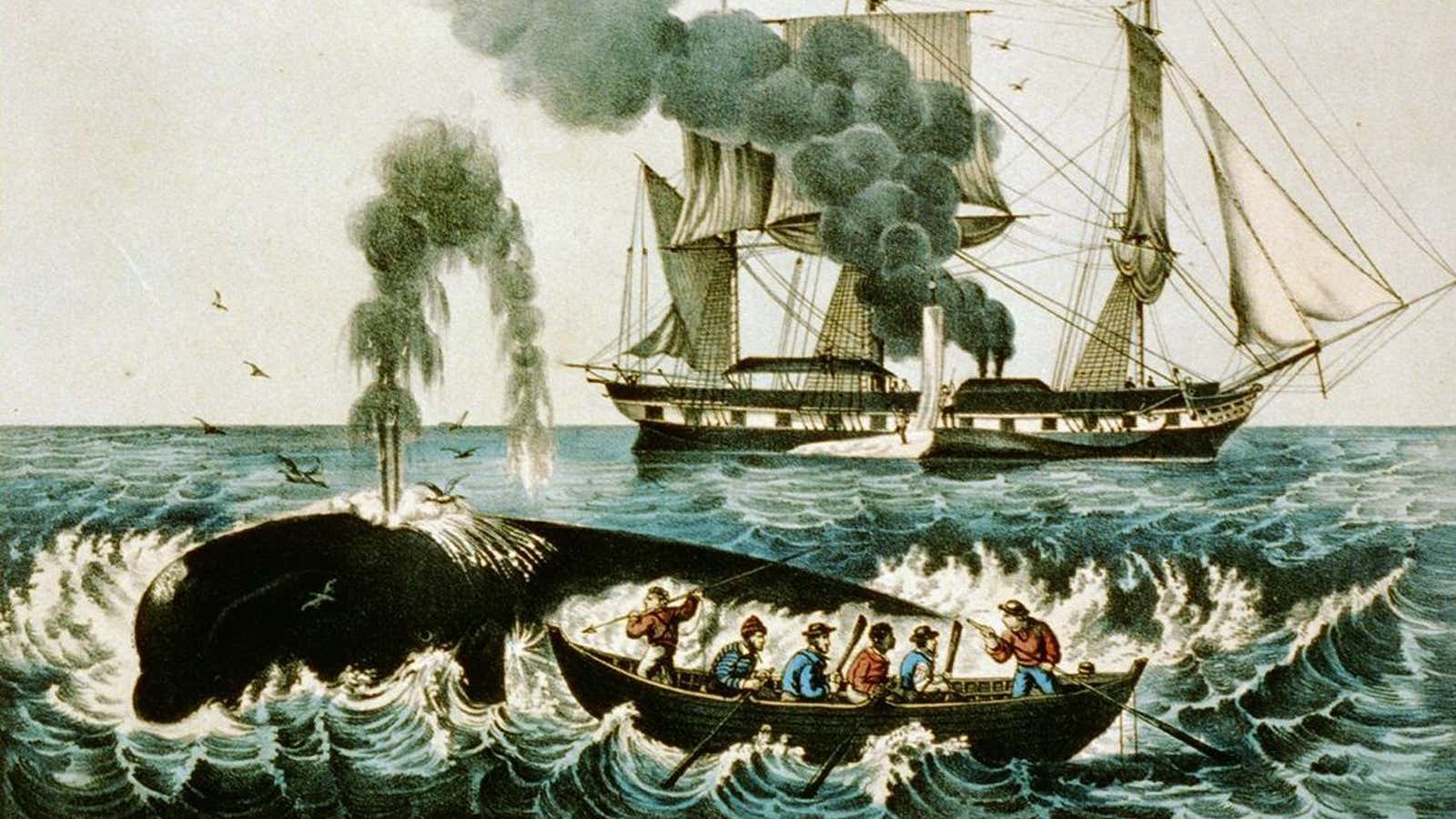

The whaling case lays out a scenario set in October 1823, when the crew of the whaling ship Atletico sights and harpoons a sperm whale. Sperm whales, prized for producing an oil that didn’t give a harsh odor when burned, were famously difficult to hunt. The safe practice was to follow the wounded animal until it was tired enough to be killed without putting up much of a fight. But the Atletico lost track of its prize, and two days later, the whale was spotted and harpooned again by the Botafogo. That ship, too, eventually lost track of the whale.

It was a third ship, the Corinthian, that found the exhausted animal. The crew harvested the blubber and ambergris, earning $11,580, equivalent to $245,000 in today’s dollars.

Once the other captains of the other ships found out their labors had profited the crew of the Corinthian, they protested, and took the case to a Nantucket judge. The rules governing ownership of harpooned whales were complex—Herman Melville devoted an entire chapter of Moby-Dick to them. The Harvard students were given an extensive briefing to help them reach a decision.

Online advertising isn’t as violent as whaling, but the attribution problems can be as complex. If a shopper learns about a product from an ad on one site, but makes a purchase based on one seen on another, which site should get credit? It’s particular a problem in mobile advertising, where shoppers are exposed to ads, but less likely to make major purchases on their phones. To address the attribution question, Facebook launched Offline Actions as part of its ad technology business. It claims to help advertisers connect offline sales to online advertising.

The stakes are significant for sellers of goods and services who need to decide where to promote their products, and for the media companies that live and die on their ad budgets. With digital advertising expected to reach $77 billion next year, surpassing the amount spent on TV, knowing which channels work and which don’t is no small issue. If it takes a lesson in whaling to help find the solution, so be it.