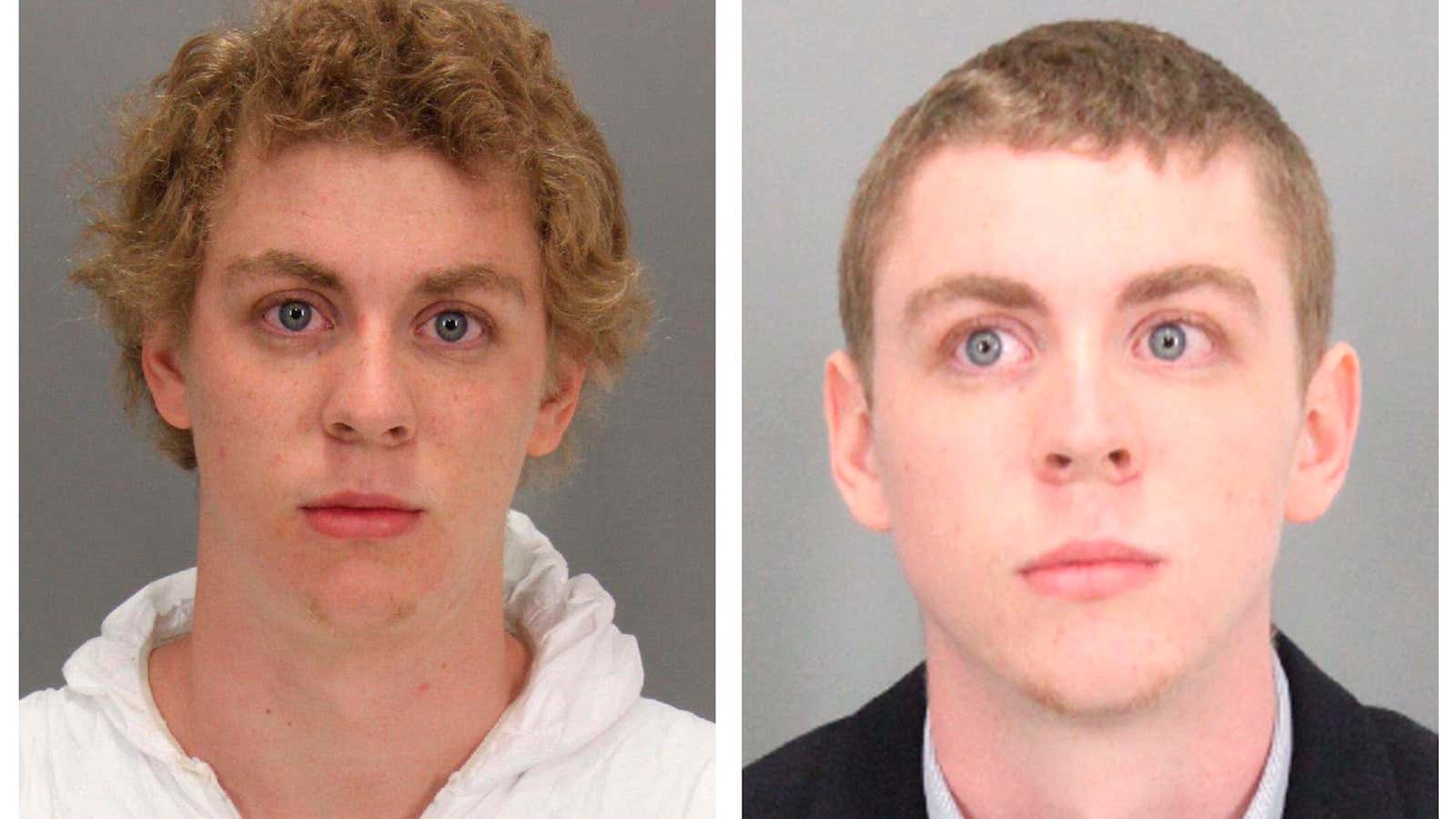

“He is a lifetime sex registrant. That doesn’t expire. Just like what he did to me doesn’t expire, doesn’t just go away after a set number of years.” In a statement released to Buzzfeed, the victim of rapist Brock Turner found a small sliver of justice in the fact that Turner, a former Stanford student, would have to register as a sex offender for the rest of his life, just as she would have to live with the effects of the assault for the rest of hers.

Turner was only sentenced to six months in jail; the leniency of the sentence has led to an effort to recall the judge. Being placed on a list seems like a small punishment in comparison to a prison term. But sex offender registries were never meant to be a punishment—and since they were introduced in the mid-1990s, they have proven to be both ineffective and often unjust.

The original goal of registries was not to provide restitution, but to protect communities. Reading the victim’s statement, it’s easy to see why sex offender registries seem like a reasonable and necessary response to crimes like Turner’s. Following a party, Turner dragged the victim behind a dumpster and penetrated her with his fingers. He was only stopped when two Swedish students physically chased him away, and then captured him. In response to his conviction, he has blamed a culture of drinking and partying on campus, rather than taking responsibility for his own violence.

Given the horrific nature of his actions, and his effort to shift blame, some might argue there’s a risk he could victimize others. Placing him on the sex offender registry, in theory, should warn communities of a potential threat. As one recent pro-registry editorial argued, “the rights of the victims, and the protection thereof, outweigh any perceived infringement of the rights of the criminals.”

The truth, though, is that there’s very little evidence that sex offender registries increase safety in any material way. A 2014 study conducted by Purdue University economics professor Jillian B. Carr of people on the North Carolina sex offender registry found that being on the registry had no effect on recidivism. That’s consistent with a 2007 report by Human Rights Watch, which looked at various studies and concluded that sex offender registries did little to prevent sexual violence.

The registry is also used to restrict residency requirements. Typically sex offenders are prevented from living within a set distance of schools or other places where children gather. Again, there is little evidence that these policies prevent recidivism or protect communities.

But there is concern that residency requirements may lead to a greater chance of recidivism or crime. After California instituted strict residency requirements in 2006, the number of homeless paroled offenders increased from 88 to nearly 2000 in five years. (Residency requirements in California were somewhat loosened in 2015.)

In Miami between 2006 and 2010, sex offenders were forced into a small colony under a bridge, because residency requirements effectively make the rest of the cities off limits. People without homes or support structures are more, not less likely to reoffend.

Some of those on sex offender registries were never a danger to begin with. Brock Turner committed a horrible crime, and there are people like him on sex offender registries who are guilty of rape and sexual assault. However, according to research by Human Rights Watch, offender registries also can include people arrested for public urination, streaking, or solicitation. In many cases, young people in consensual relationships—a 17-year-old convicted of intercourse with a 15-year-old boyfriend or girlfriend—end up on registries as well.

Politics can end up in the mix as well. “Sodomy was illegal in your and my lifetimes,” Erica Meiners, a professor in the college of education at Northeastern University who has researched sex offender registry issues, says. “Gay people or men who had sex with other men who are still targeted for things like lewd and lascivious behavior or public sex, can also be found on registries.”

Meiners pointed out that the preventative intent of registries, is based on a common misconception about sexual violence: the myth of stranger danger. “Registries really operate on this idea that these are the bad people, and if we have a scarlet letter on the bad people we’re going to be able to prevent or reduce child sexual violence,” she says. But the truth is that less than a third of sexual violence is committed by strangers. Most victims know their assailant.

Indeed, belief that you can find the bad people, isolate them, and keep everyone else safe, is a driving force behind criminal justice policies generally—and is part of why addressing mass incarceration in the United States remains so difficult. Discussions about ending mass incarceration generally focus on nonviolent drug crimes. But the truth is, as Fordham Law professor John Pfaff has written, those convicted of drug crimes still serve short sentences. In state prisons, which house the bulk of prisoners in the United States, the majority of prisoners are serving time for violent crimes, not drug offenses.

Politicians rarely discuss the need to reduce terms for violent offenders, however. Instead, violent offenders are seen as having given up their right to freedom—potentially forever—with no possibility of reform. Sex offender registries follow the same logic. Sex offenders are always a threat, and always deserving of punishment and stigma.

The damage sex offenders do, as Turner’s victim said, can last forever. But sex offender registries do little to prevent future crimes, and very little, as Turner’s victim’s letter also demonstrates, to provide a sense of justice and restitution for victims.

The quickest solution to the failures of registries is simply to get rid of them. Only a handful of countries in the world have them, so it’s not as if the United States would be embarking on an unprecedented or dangerous policy if it eliminated them. Addressing sexual violence effectively, however, is a much more difficult problem. “If we really want to stop the next Brock Turner,” Erica Meiners says, “we need different kinds of conversations about consent, different kinds of conversations about masculinity, what it means to be a man, how we think about heterosexuality. We know that having Brock Turner on the registry isn’t going to solve the problem.”