If prime minister Shinzo Abe’s effort to jolt the economy back into action works, Japan will owe a real debt of gratitude to… Ben Bernanke.

The chairman of the Federal Reserve makes monetary policy for the US, of course, not Japan. But the new governor of the Bank of Japan (BoJ), Haruhiko Kuroda, was channeling the spirit of Bernanke when he announced bold new efforts today to ease financial conditions and generate inflation in a larger-than-expected round of bond purchases.

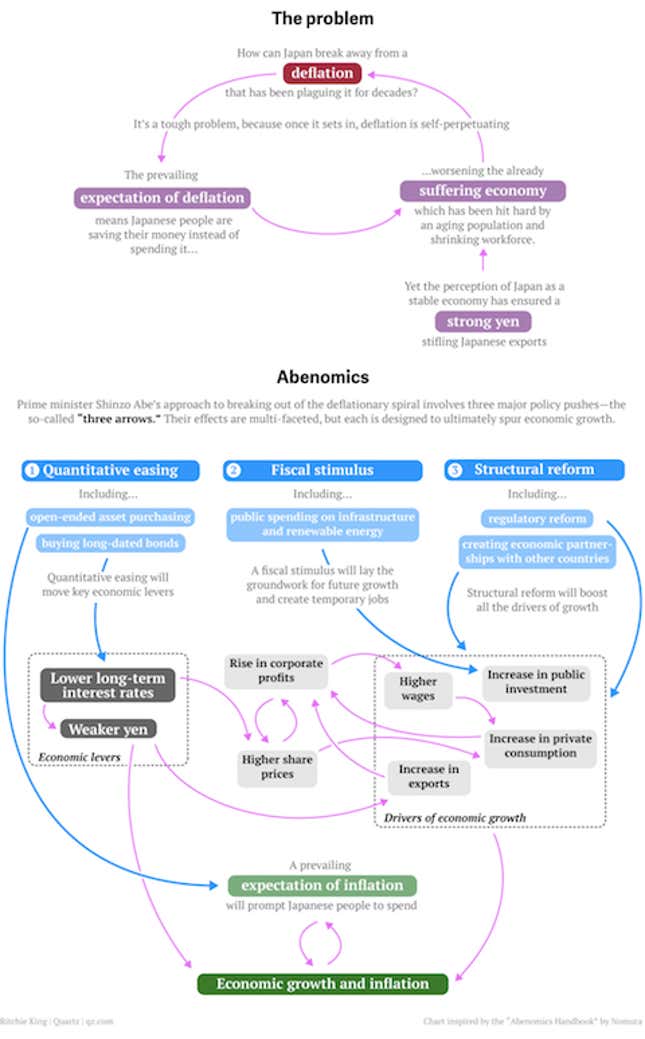

The BoJ will buy the bonds with freshly printed money, a method of lowering interest rates known as quantitative easing. This is a major component of Abe’s three-pronged approach to re-energizing Japan, which has become known as Abenomics.

It’s also been a hallmark of the Bernanke Fed since the financial crisis hit. In normal times, central banks just raise or lower target interest rates in order to loosen or tighten the credit spigot. After the crisis, the Fed dropped interest rates almost to zero, which is sort of like flooring the US economic engine’s gas pedal. Yet instead of roaring ahead, the US economy continued to putter forward listlessly.

Bernanke could have thrown up his hands, saying, “I’m stepping all the way on the pedal. Guess there’s nothing else we can do.” But he didn’t. The Fed engineered a slew of programs aimed at getting the engine going.

The Bernanke Fed’s ability to improvise would have impressed Dizzy Gillespie. There were, of course, the various rounds of money creation. The first quantitative easing (QE) program arrived during the worst of the financial crisis. Then there was a second, QE2, in 2010. Then the Fed unveiled a QE-like program known as Operation Twist, which was later expanded and ultimately smushed into QE3, a commitment to keep buying securities until the economy improves.

But there have also been bold experiments with the Fed’s considerable bully pulpit. Bernanke introduced an explicit inflation target to replace a vague commitment to “price stability”; public economic forecasts from members of the Fed’s all-important Federal Open Market Committee; and a press conference after monetary decisions. Any one of which would have been a big move for any previous leader of the notoriously risk-averse institution.

There are risks to such experimentation, of course. Some doubt that the Federal Reserve will be able to head off future inflation, if it emerges. Others say the US economy’s continuing frailness shows Bernanke’s approach has failed.

And that’s fair enough. It’s difficult to argue that any individual Fed effort has achieved much. Even so, the US economy is clearly far better off than Europe’s or the UK’s, which also suffered shocks during the financial crisis. Neither the European Central Bank nor the Bank of England responded with anything like the vigor of Bernanke’s Fed.

A license to be creative

Compared to the BoJ, though, the British and European central banks have been practically hyperactive. More than two decades after Japan’s real-estate crash and subsequent banking crisis, the BoJ has made little progress on beating back deflation. (As an aside, deflation—persistent falling prices—may sound good if you’re sick of prices always going up. But it acts as a huge headwind to economic growth, because it prompts people to repeatedly delay spending in the hopes of paying less.)

As a result, GDP growth has generally hovered somewhere between negative and anemic. And yet under its recently departed governor Masaaki Shirakawa—who helmed the BoJ for nearly five years—the bank took little aggressive action to turn things around. ”Incremental steps of the kind we’ve seen so far weren’t going to get us out of deflation,” Kuroda said Thursday, in announcing the bank’s new push.

Before Bernanke’s era at the Fed, such an aggressive effort by the BoJ would have been seen as pushing the edge of monetary probity. But the Bernanke Fed’s willingness to push the envelope has opened up a whole new area for central banks to operate in. And that could offer Japan the opportunity to slough off its economic slumber in a way the markets can understand. Case in point: This quote a market observer offered the Australian Financial Review:

“Previously the Bank of Japan was a real impediment to exiting deflation because they didn’t think that they could fix it,” [WestPac senior economist Huw] McKay said. ”So they were actually a stumbling block to creativity. You need to get creative under these circumstances. Ben Bernanke is very creative.”