Kevin MacRitchie surveyed the inferno spreading across Diavata refugee camp. From his vantage point on the roof, where he had been fixing a satellite dish, he could see a column of thick black smoke twisting toward the sky above two rows of incinerated tents. While Greek army and police helped battle the fire, a protest had erupted at the front gate, by Syrian refugees frustrated with conditions in the camp and the asylum backlog that was keeping them there.

That meant MacRitchie was now alone. His teammate, David Tagliani, had run out to drive their equipment van into the camp, and in the meantime, the angry mass had blocked the entrance. Yet when they recognized Tagliani behind the wheel, the protestors stopped. “Wifi,” they called to each other, “wifi.” And they cleared a path to let the van pass.

The police, army and refugees could agree on at least one thing, it seemed. They all dreaded a day without internet.

* * *

MacRitchie is the director of connectivity for NetHope, an NGO first created in 2001 to improve the use of technology by the humanitarian sector. Back in April, UNHCR, the UN’s refugee agency, had asked NetHope to install wifi internet access in seven priority camps in northern Greece. (Disclosure: I was volunteering for NetHope at the time and published some posts on its blog.) The first team worked at a breakneck pace, at times getting internet live within hours, even in remote camps with scarcely a power line in sight. Fifteen-hour work days were routine.

Their work was rewarded with bigger calls for help. NetHope is now coming to mainland Greece for two weeks a month. (In between deployments, MacRitchie is a Michigan buffalo rancher who moonlights as a mounted sheriff; he has the badge tattooed on one arm.) The June team would service or connect wifi at a staggering 21 campsites across Northern Greece, all in the space of 14 days.

Early on a recent morning I sat with MacRitchie and Matt Altman, NetHope’s lead systems architect, on loan from Cisco, as they pored over a map of 43 Greek refugee camps managed by the UNHCR. Then they loaded up the vans. Altman took the wheel in a rental packed floor-to-ceiling with boxed routers, folding ladders, coils upon coils of cable, crimpers, a working 4G wifi hotspot, and the odd bottle of Pepsi. It looked a bit as though the Cable Guy had commandeered the Scooby Doo Mystery Machine.

* * *

UNHCR has been setting up refugee camps around the world for six decades, but only recently has it begun stressing the importance of internet connectivity. “Refugees need wifi,” UNHCR camp manager Marie Beniot told me back in April, on opening day at Lagadikia camp. Among the first questions asked by the Syrian families unpacking their suitcases in Lagadikia was “when will we get wifi?”

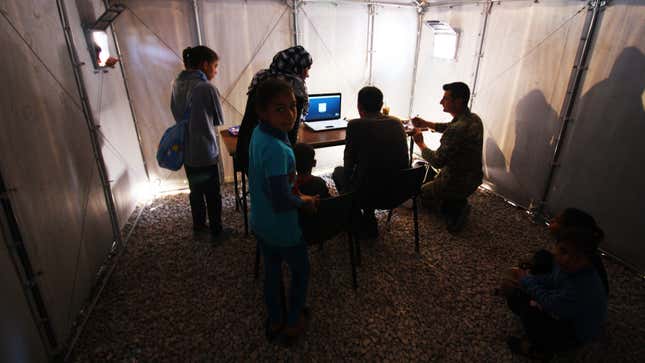

Their need is far from frivolous. The only way for refugees in remote camps to book appointments with the Greek asylum office is via a Skype line, open one hour per day for each language. People also use the web to contact friends and family who have been separated by closing borders or left behind in home countries. Facebook groups spring up to help people find jobs and places to live. WhatsApp and Facebook are the top two services accessed from camp networks.

Wifi is essential because few refugee families can afford a data plan. Many say they have all but exhausted their money and worry about conserving it for an indefinite stay in Greece. The average stay in a refugee camp globally is 17 years.

But the provision of wifi has often been haphazard. In past humanitarian emergencies, assorted government agencies, NGOs and private groups have descended on a disaster zone, deploying disjointed communications networks. At best, this has led to duplicated efforts and wasted money. At worst, signals have interfered with one another, adding to the chaos. It’s as if fifty separate cargo planes flew in to an earthquake zone to hand out fifty types of sandwiches.

Then the big players put their heads together. Why not coordinate the deployment of communications technologies in an emergency, the same way that the World Food Program coordinates food aid? They called in NetHope. Today, it is a consortium of 49 NGO members, including the Red Cross, Save the Children and Oxfam, and three dozen financial backers from Microsoft to USAID. Since its founding, NetHope has responded to disasters from the Southeast Asian tsunami to the Ebola outbreak in West Africa.

In 2015, the UNHCR asked it to set up wifi hotspots up and down the Balkan migration route, where over one million migrants were traveling from Lesbos through Macedonia to northern Europe. Then, in March of this year, the borders closed. Macedonia shut its doors to migrants, and the EU began deporting new arrivals back to Turkey. Refugees trapped in Greece were directed to camps built in former military outposts and abandoned buildings. UNHCR turned its attention toward supporting them for the long haul.

* * *

The toughest part of the installs is getting permission. To set foot inside a government-run camp, groups need authorization from the Greek army and police force, the interior ministry, and UNHCR. Even with all the right seals, stamps and letters, NetHope was frequently denied access in the beginning. Then word spread among officers that some of them could get wifi on the job if NetHope was allowed to work. The gates began to swing open more easily.

Power in the camps is also a constant problem. At Sinatex, a former factory that now houses 600 refugees from the shuttered Idomeni squatter camp, there was plenty of power around the perimeter of the factory building. Unfortunately, some Syrian men were busy ripping out and splicing the wires in order to run private lines into their families’ tents. MacRitchie, unfazed, told the team to place a sticker on every wire connecting the wifi access points with the following words in Arabic: “if you remove this, the internet will go down.” The hope was that even in a refugee camp, no one wanted to be that guy.

Occasionally, NetHope has channeled refugees’ ingenuity toward a higher purpose. In Lagadikia, it had hired a Syrian electrical engineer to build 30 charging stations. In other camps, men looking for a break in the monotony have been eager to help, even if just to hold the ladder.

* * *

Refugee-camp wifi is a lot like in-flight wifi, and with the same list of downers: No porn, violence or malware, no video streaming, and a ceiling on bandwidth per user. This is all for good reason, Altman explained. “Signal loss means that even a 20MB DSL line will serve us 2-4MB,” roughly the same as airplanes. “If you divide that by one hundred users at a time, you’ll see why we cap at 128KB of data per user. We don’t want a single person hogging all the bandwidth.”

Most refugees at Sinatex were just happy to be connected. Men and women approached the NetHope team to give a thumbs up and “Wifi, thank you.” One Syrian couple looked dismayed: “No YouTube.” Knowing that the factory would likely be their home for years, it was hard to fault them.

Not all camps are created equal. Cherso camp is plagued with problems, beginning with its location on a remote, snake-infested hill. At times, strong winds tear down power lines and equipment; at others, refugees’ hands do the tearing. At least once, the military or police has simply shut off the wifi.

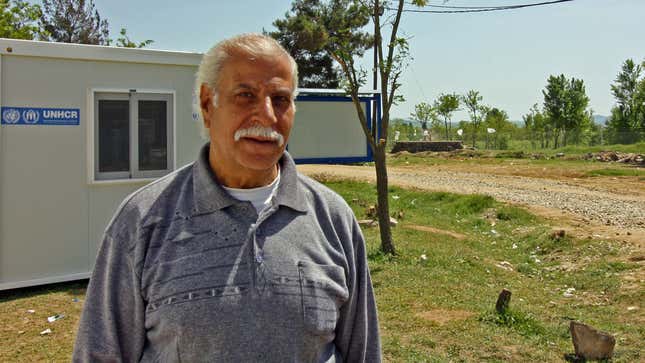

Recently, NetHope rolled into Cherso to find that someone had shredded the tent covering their charging station. (I wondered if the canvas where someone had scrawled “KURDISTAN” was destroyed first.) Plenty of people were counting on an internet connection. A 74-year-old Syrian named Atallah Taba told me he used NetHope’s wifi to Skype with his daughter in Germany for the first time in two years. Then he said after the calls he often went to his tent to cry.

Diavata camp is a different universe. Within days of the fire in April, there was hardly a trace of the accident. Instead of tightening their control over the camp, the UNHCR and Greek government authorities had expanded new privileges for refugees. First, they rigged up a Skype booth, letting refugees use the army major’s personal laptop to dial the asylum office. Later they extended the hours so that people could dial family members, too. People in Diavata seemed to be getting along fine. “We love the major,” a young Syrian man gushed.

“In Haiti, they held up signs that said ‘I am hungry,’” Isaac Kwamy, NetHope’s director of emergency response, told me. “Here, they hold up their phone to say, ‘we need wifi.’ We need to tell the world that access to information is aid.”