Since the formation of the European Union in 1991, it’s been an article of faith among its champions that the forces that gave it birth would move it in only one direction. “Progress towards an ever closer union” is enshrined in its founding language.

The logic of this path is unescapable: Separately, Europe is 50 or so picturesque tourist attractions. Together, the EU is a 500 million-person bloc capable of competing in a world of superpowers. The aftermath of the financial crisis, and especially the drama surrounding Greek debt, helped make the case for deeper integration. The euro zone, which includes 19 of the EU’s member states, issues its own currency and sets interest rates, but it and the union’s eight other members (excluding the UK) do not form a fiscal union, with the ability to set taxes and control spending at a pan-European level. To bring Greece and other struggling economies under control, it seemed clear the nations of Europe needed to give up more sovereignty to a central government that would enforce policy discipline.

But while seismic economic and political pressures are pushing Europe closer together, the powerful centrifugal forces of uncertainty and millennia of history and cultural identity are pulling it apart.

Britain has historically been an awkward fit in the EU. An island nation happy to keep an arm’s length distance from the tumult of the continent, the UK’s ties to Europe are rational, not emotional. The economic case for staying in the EU couldn’t persuade voters who didn’t feel its benefits, had no stake in the union’s future, and saw only reasons to fear it. For millions of voters driven by anxiety or outrage, Britain’s EU experiment with the “United States of Europe,” advocated by Churchill in 1946, has run its course.

Supporters of the EU fear Brexit is the first domino to tumble, leading to the unraveling of the union. But the UK is an unusual case in Europe. It’s been a coherent, defined nation in its present state for more than 300 years, and the concept of England arguably stretches back more than a 1,000, depending on whether you want to start with William the Conquerer or Alfred the Great.

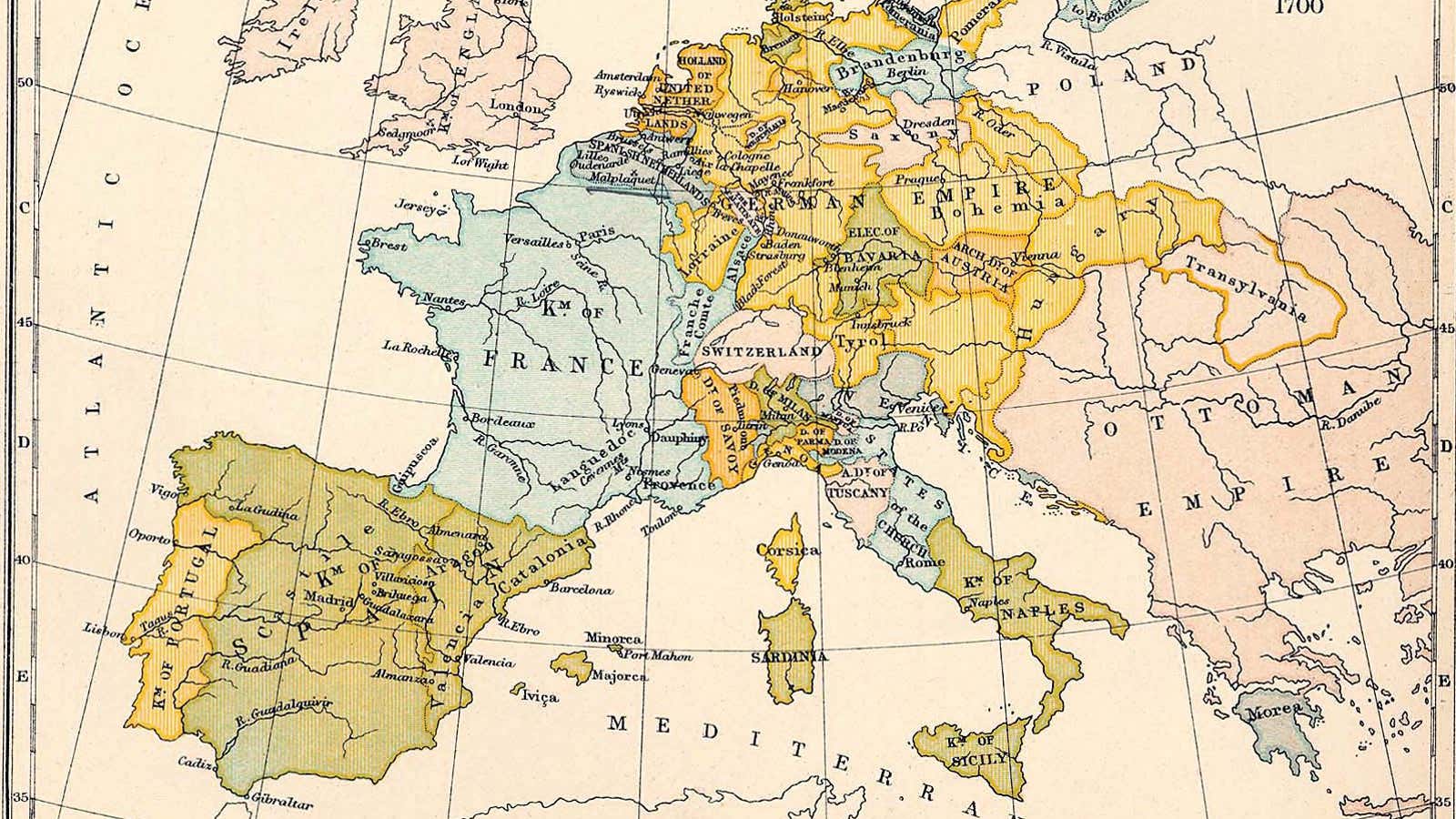

France, too, has an ancient history. But other European nations are more recent creations. Germany comes from a collection of princely states, once part of the Holy Roman Empire, that weren’t hammered together until 1871. The Kingdom of Italy was founded in 1861, assembled out of Sardinia, Lombardy, Sicily, and the Papal states. Spain is older, cohering under the Hapsburgs in 1516, but for centuries Catalonia and the Basque country have bridled under its rule. Belgium, founded in 1830, still acts like two separate nations.

For these and other younger or fractured countries, uniting as part of Europe is less wrenching. They’ve already had the experience of surrendering control to a larger entity and have more or less made their peace with it. For ethnic enclaves like Catalonia, a more united Europe, and a less united Spain, would offer the twin advantages of economic clout and local autonomy. Scotland saw a similar dynamic and voted to remain. From Slovenia to Luxembourg, membership even in a union as imperfect as the EU makes perfect sense.

Jacques Delors, one of the founders of the EU, made the case for further integration by saying, “Europe is like a bicycle, you either pedal or you fall.” But Brexit shows us that not all members were interested in riding toward the same finish line.