With all due respect, Britain doesn’t really matter that much.

To be sure it’s upsetting to see the UK political establishment—both major parties—being torn asunder amid a significant turn inward for one of the world’s great democracies.

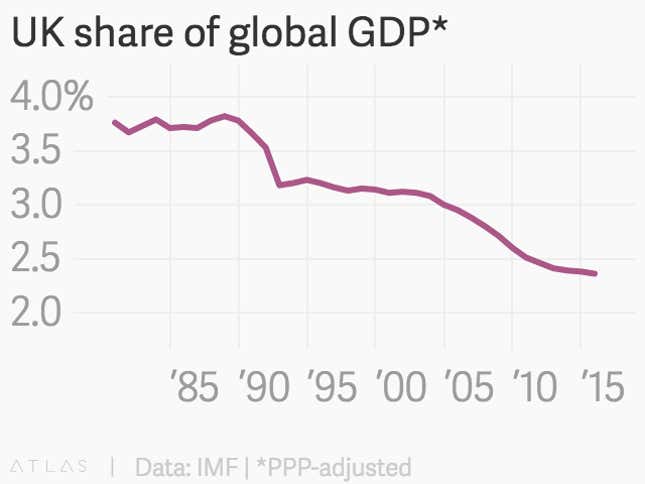

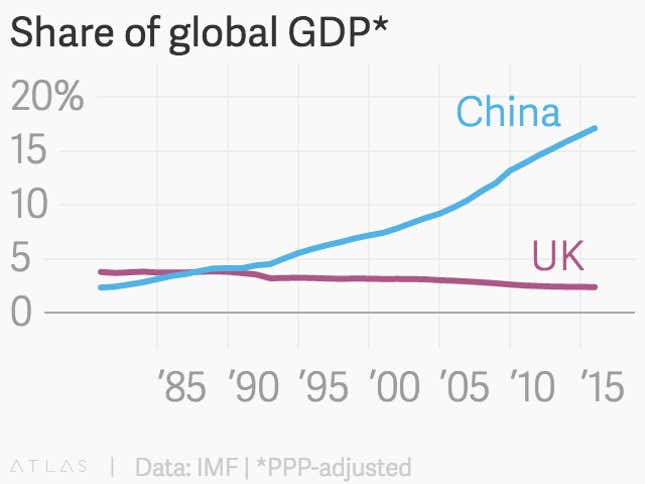

But when we’re talking about the future direction of the global economy, Britain has been playing a diminishing role for decades.

According to the IMF, the UK accounted for roughly 2.4% of global GDP in 2015, down from about 4% in the early 1980s. This means that the slowdown in the UK will barely nudge the world’s large economies at all. For example, Goldman Sachs economists now estimate that the spillover effects on the US economy from the Brexit vote will be a scant 0.1%.

No, if you’re looking for something to worry about, spin the globe and plant your pudgy finger on the People’s Republic of China, which continues to grapple with an economic slowdown that has significant implications for almost every country on earth.

Data released July 1 on the country’s all-important manufacturing sector show a deepening contraction there, with the June number falling to 48.6 from 49.2 in May. (Anything below 50 indicates contraction.)

If there’s any good news, the slowdown in China’s manufacturing activity seems to be offset to a certain degree by an uptick in services. This is a positive sign, as China must make an economic transition away from export-driven manufacturing if it wants to produce more sustainable growth. (There simply aren’t enough customers outside China for all the factories that have been built in the People’s Republic to keep busy.)

Chinese policymakers are trying to carry out this difficult transition in the incremental, tightly controlled, less-than-transparent way we’ve come to expect from the authoritarian regime. That approach stands in stark contrast to the abrupt, public, and democratic turn the United Kingdom took in the recent EU referendum.

But while they are much quieter, the changes in China remain vastly more important to the global economy as a whole.