When it comes to privacy controls, we may now have too much of a good thing. Smartphone owners must now make more than 100 privacy decisions about how how much data their apps can share on Apple’s iOs and Google’s Android operating systems. That number will only climb as privacy settings affect more of our devices and software.

The result is not more privacy. It’s confusion. “Most people although they care about privacy won’t spend huge amounts of time playing with those settings,” said computer science researcher Norman Sadeh at Carnegie Mellon University in an interview. “Doing the right thing in this space means, in principle, giving more control to users but it becomes unmanageable and underused. We’ve developed technology to assist users with these settings”

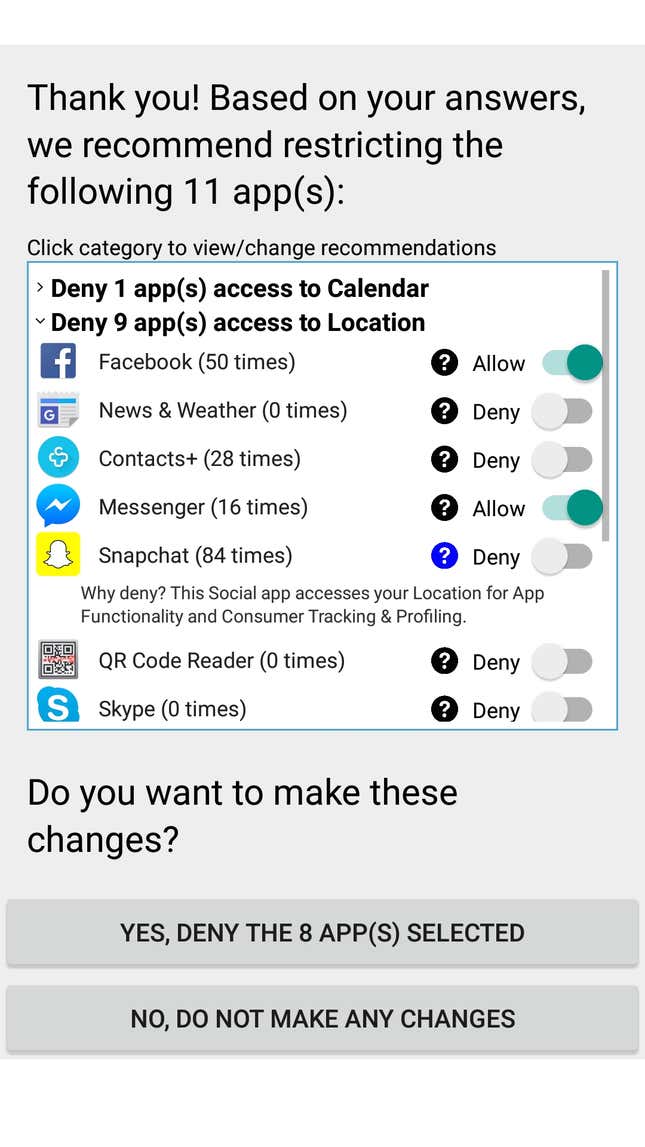

Tired of waiting for the tech giants to fix the problem, Norman Sadeh’s team at Carnegie Mellon University developed a personal privacy assistant app powered by machine learning. The app learns your preferences by asking a few key questions about privacy, and a machine learning algorithm uses this data to group users into distinct profiles. The app can then make recommendations and give users a single dashboard to manage their data and privacy settings.

The CMU team presented findings from a study with the app at the Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security in Denver this June. Users accepted 79% of the app’s privacy settings recommendations significantly reducing the time users needed to select the desired privacy controls (about 20% of the settings were entered by users, and only 5% were changed from the app’s recommendation). Participants were also generally permissive. Of the 3,559 app requests for data, users rejected only 19% in their privacy settings. The most likely to be rejected were requests for phone call histories (almost half), while camera access was most accepted (95% acceptance).

The key to solving the problem was obtaining accurate data on peoples’ preferences. Earlier research has shown smartphone users are typically unaware of the data apps collect (and uncomfortable once they find out). Drawing assumptions from people’s default settings for that reason doesn’t work. Instead, Sadeh elicited people’s preferences in an earlier study by creating “privacy nudges” (short messages such as “Your Location has been Shared 5,398 Times“) to prompt them to re-evaluate their privacy settings. More than half added additional restrictions.

Even though desire for privacy is strong, commercial demand is not. Privacy controls still rank as a “secondary task” for smartphone buyers, says Sadeh. People rarely spend much time or money on it. It needs to be easier for people to adopt it. The security-conscious Blackphone, marketed as “NSA-proof” by the Swiss privacy outfit Silent Circle and Spanish smartphone maker Geeksphone, only sold 6,000 units to distributors despite sales predictions of 250,000, reports The Guardian.

That makes privacy something that has to be solved by closing the distance between the users’s desire to safeguard their data and the complexity of doing so today. By using machine learning to simplify personal privacy settings, Sadeh believes “we can help overcome this gap,” he said.

The app will roll out on the Google Play store later this summer. At the moment, it’s available only to users who have “root access” to their smartphone’s Android operating system, the equivalent of a jailbroken iOS phone, so the app has access to phones’ permissions. The team will release a workaround later in the year, although an iOS version is not expected immediately. Sadeh, who says Apple and Google have legitimate concerns about exposing those permissions, expects the operating systems will eventually allow secure access to the controls to manage privacy settings.

Maybe people will start using them.