Germany will finally apologize for its other genocide. In a landmark admission of historical guilt, chancellor Angela Merkel said her country will formally recognize and apologize for the systematic murder of Namibia’s Herero people more than a century ago.

Germany’s federal government is in talks with the Namibian government to finalize a common language and policy around the hitherto almost ignored mass killing, the chancellor’s office said this week according to AFP. Still, Merkel’s government was clear that there would be no reparations, but rather targeted development projects.

“On the question of whether there could be reparations or legal consequences, there are none. The apology does not come with any consequences on how we deal with the history and portray it,” Sawsan Chebli, Merkel’s spokeswoman, told reporters.

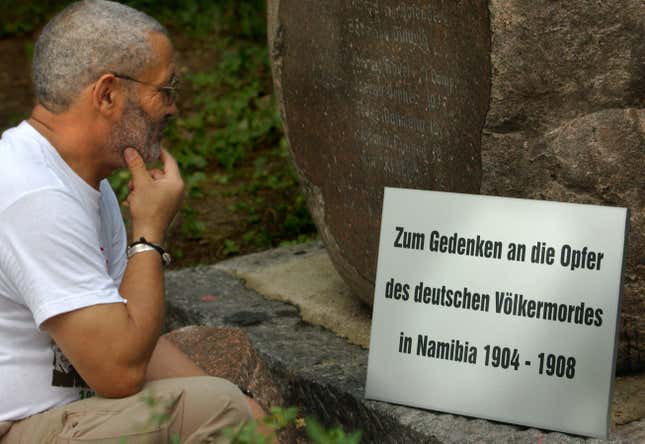

The genocide is widely viewed as the first of the twentieth century, perpetrated from 1904 to 1907, but is rarely recognized. Historians believe that the atrocities perpetrated by the German troops became a precursor for those perpetrated during the Holocaust. The parallels between Germany’s two genocides are chillingly similar: the extermination order for the sake of expansion, forced labor in concentration camps and scientific experiments on prisoners.

Within three years, German troops oversaw the extermination of 85% of the Herero population, expropriated their land and seized their source of wealth, their cattle. Today, the once powerful Herero make up about 10% of Namibia’s population and live in some of the country’s most underdeveloped regions, struggling with high youth unemployment.

A former German minister first apologized to the Namibians twelve years ago. A hundred years after the systematic killing of the Namibian tribes began, Germany’s then development minister Heidemarie Wieczorek-Zeul travelled to Namibia in 2004 and acknowledged the atrocities committed were in fact genocide. It would take another decade before genocide would enter Germany’s policy towards Namibia.

A century before, another German official was sent to Africa to suppress local revolt against German colonialism. General Lothar von Trotha arrived in what was then South-West Africa to quell a rebellion by the Herero and Nama ethnic groups. The Herero were until then one of the region’s wealthiest tribes, their cattle roaming over a third of Namibia’s vast countryside. Until van Trotha’s arrival, they had managed to keep German colonial expansion at bay.

“The Herero people will have to leave the country. If the people refuse I will force them with cannons to do so. Within the German boundaries, every Herero, with or without firearms, with or without cattle, will be shot. I won’t accommodate women and children anymore. I shall drive them back to their people or I shall give the order to shoot at them,” van Trotha ordered.

The Herero faced the German onslaught with little more than spears, bows and a few rifles. Those who weren’t killed were driven into the desert. There, German troops sealed off the perimeter, poisoned their wells and bayoneted anyone who tried to escape dehydration, known as “march into death” for the Herero.

Those who survived the desert were herded into concentration camps and were forced to dig up Herero graves to retrieve the skulls of their dead relatives. Women were forced to skin and boil the skulls, which were used in German experiments to prove Aryan superiority and African inferiority. Of the more than 80,000 Herero population, only 15,000 survived.

Those skulls were returned in 2004, according to a report then by the Associated Press. The pain of an unacknowledged atrocity was still fresh, with tears and anger as the remains of their ancestors were brought home. Today, Namibia is a fast developing country, with a sound economic policy diversifying from diamonds and other commodities to renewable energy and tourism. Still, many of the country’s historical pains must still be dealt with.