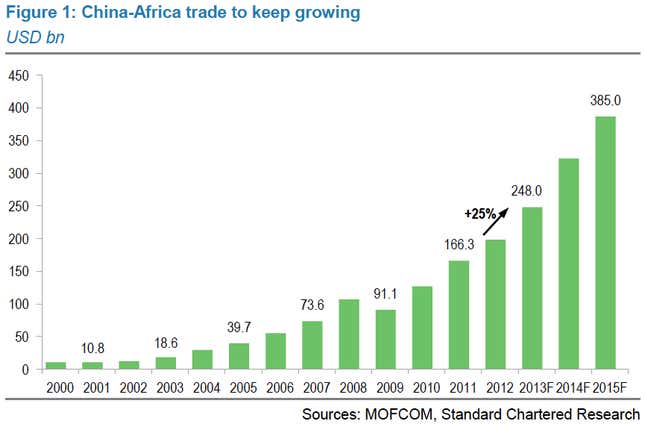

China’s economic relationship with Africa is growing at a breakneck pace. In 2012, the volume of trade—imports plus exports—reached $198.5 billion. Standard Chartered analyst Sarah Baynton-Glen estimates that trade volume could amount to $385 billion by 2015—nearly double its current level—if it continues to grow on its current trend.

By comparison, trade between the US and Africa amounted to $108.9 billion in 2012.

But the linkage between Africa and China goes deeper than just trade volume. Growth in Africa is a way for China to stake out its growing economic dominance—and the importance of the yuan (which goes by the code CNY) as a global currency. More and more trade between China and Africa is being settled in yuan, an important step towards establishing it as a reserve currency. Eventually, it seems that China will encourage more African corporations to issue corporate bonds settled in yuan and convince African central banks to hold it as a reserve currency to diversify their portfolio and as a symbol of their trade relationship.

This process is off to a promising start. Baynton-Glen cites a handful of notable developments: The Central Bank of Nigeria announced that it would hold up to 10% of its currency reserves in yuan in 2011. South Africa, Kenya, and Ghana—for whom China is an important trading partner—have also made murmurs about diversifying into the Chinese currency. This is something China wants; last year, People’s Bank of China Deputy Governor Li Dongrong predicted (“optimistically,” according to Beynton-Glen) that 20% of African central banks’ assets could be denominated in yuan by 2020. The analyst writes:

For African central banks, the reasons for increasing CNY in reserves are clear. Higher yields and expectations of CNY appreciation will help boost returns on FX reserves.

But perhaps even before that, Baynton-Glen predicts that some African companies—first in South Africa, then Nigeria, then other highly rated African countries—are likely to begin issuing what are commonly referred to as “dim sum” bonds, which are yuan-denominated bonds issued in Hong Kong, allowing foreigners to invest in them freely:

For African issuers looking to finance capital expenditure plans, issuing bonds denominated in the CNY provides access to a new investor base, enables expansion of existing financing channels, and offers a lower cost of financing than do bonds available from other international capital markets.

Whatever the first move, the love affair between China and Africa appears to be blossoming.