On the internet, everyone is within shouting distance. When you WhatsApp, Slack, or email your friends or colleagues, you probably don’t think much about the path your message follows as it wends its way from your phone to theirs.

But even if you did care, it would be almost impossible for you to figure it out.

The internet is made up of many different networks, controlled by many different kinds of companies. Each of those networks makes decisions about where to send messages independently of all the rest. They are connected, loosely, by a system called the Border Gateway Protocol, which is sort of like a telephone directory that allows one network to find another one.

The independence of each individual network operator is what has allowed the internet to spread organically around the world. It requires very little coordination to set up an new internet outpost in an underserved area. However, this center-less system also means that users of the internet have no control over which particular networks handle their data or where they are physically located. Sometimes, your data travels to surprising places—including to countries with dubious privacy laws or a history of cybercrime.

A single message crossing the internet might pass through as many as 40 computers and spread through a dozen different networks. All of those computers could be located in one country or they could be spread across the globe. The connections between them are often made one by one: Each network operator tries to establish connections that ensure its users have the fastest possible routes to the rest of the world. Sometimes this involves payment, but others simply trade—each company agrees to pass the other’s data along. Rarely does the home country of the network operators enter into those agreements.

Over the past decade privacy and security concerns have pushed many countries to seek greater control in how the internet operates within their borders. EU countries, frustrated that so much of their citizens’ data is stored abroad, in countries with very different privacy expectations, have passed laws requiring all companies offering services to EU citizens to follow strict rules when storing data outside the EU. However, as Edward Snowden revealed, information traveling across the internet is at risk of being intercepted by the US National Security Agency, even if it only passes through US networks on its way somewhere else.

It seems like there should be a simple fix: If you don’t want your data to go to a certain country, then don’t send it there. However, the autonomous nature of the internet makes it difficult for businesses and nearly impossible for individuals to control where their data travels. Each network that touches a message is generally oblivious of the full path it takes. As a result, even if countries were to pass laws to, for instance, keep traffic out of the US, they would be impossible to enforce.

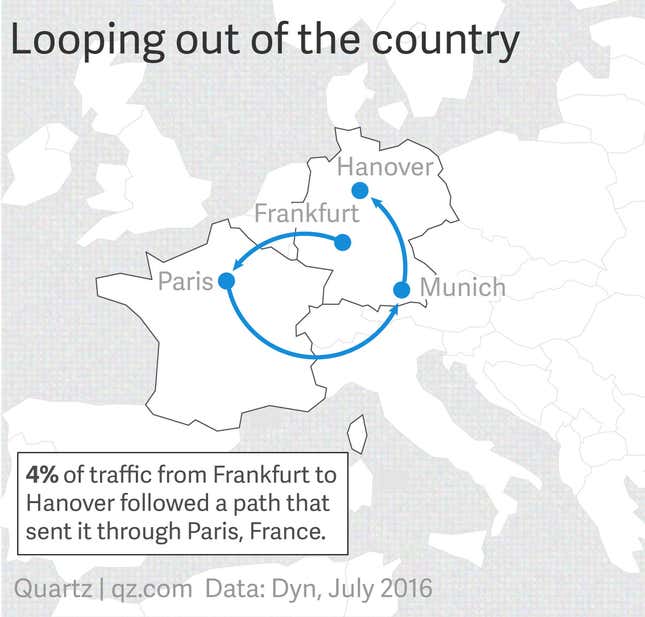

Even seemingly trivial routes can be surprisingly complicated. According to Dave Allen, a vice president at internet monitoring firm Dyn, who provided data for this story, messages that begin and end in the same country often ”boomerang” out into a third country. This might be something as innocuous as an email, or it could be a local bank transaction.

Internet routing can also be intentionally abused. Cybercriminals have been known to sometimes publish fake routes in the BGP in order to hijack traffic meant for a legitimate service. Network operators that fail to spot the fakes can end up sending messages to entirely the wrong place. A savvy hijacker will take what she wants and then forward those messages on to their original destination, leaving the user unaware anything has gone wrong.

Even in the absence of sophisticated cyber-criminals, the internet’s phone book is vulnerable to mishaps. In 2004, an error by a Turkish ISP essentially routed the entire public internet through Turkey. A similar mistake in 2008 sent all of YouTube’s traffic to Pakistan. In a situation like this, Google has few options for an immediate fix. It has to wait for networks that adopted the bad route to realize their mistake and correct it.

Short of re-architecting the entire internet to use more secure protocols, the only defense available to internet companies is careful monitoring. Companies such as Dyn use a huge number of internet observatories to measure where traffic is routed—and when it goes to unexpected places. In the event traffic does go somewhere unwanted, companies may need to move to an entirely different service provider in order to avoid that path. Encryption also plays an important role, but you probably don’t want your traffic being siphoned off by a hostile surveillance state, even if it is encrypted. Encryption could always be broken.

Re-architecting the internet is not quite not as far-fetched as it sounds. In fact, the Internet Engineering Task Force, which governs internet technology, adopts new standards on a fairly regular basis. A draft proposal for securing the BGP has been under revision since 2011 (a far cry from the “three napkins” it took to create the BGP originally). The trick, of course, is making a change to the core technology of the internet without breaking anything—even for network operators that fail to implement it promptly.

In the meantime, for internet users, there is literally nothing to do but wait.