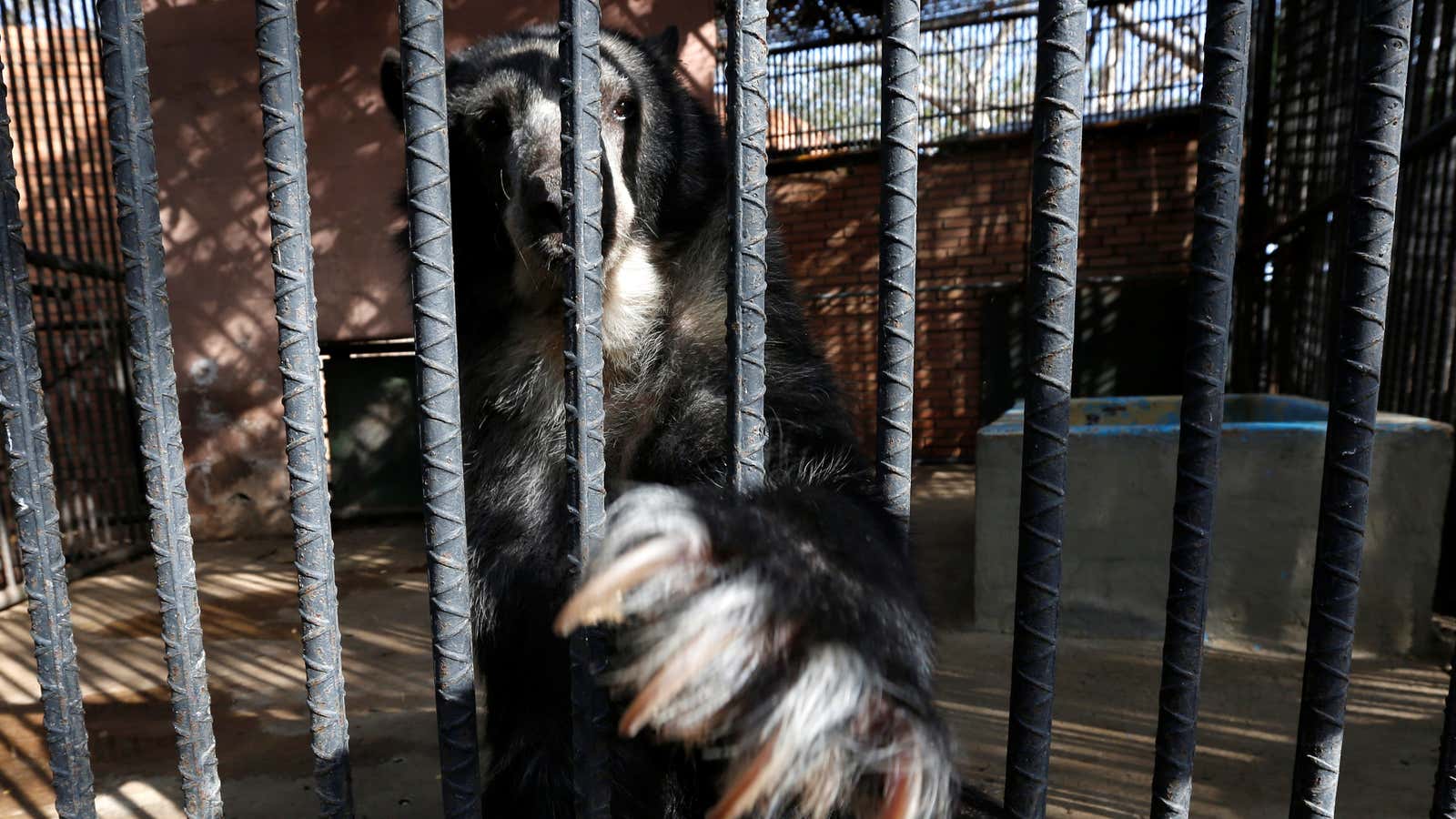

It’s a tough time to be a living thing in Venezuela, whether human or animal. Some 50 birds, rabbits, Vietnamese pigs and tapirs perished of hunger over the past six months at a Caracas zoo, Reuters reported. At another, carnivores such as lions and tigers are being fed mangoes and pumpkins to replace overpriced meat. At yet a third zoo, in northwest Venezuela, bears are making do with just half of their required calories.

It’s yet another dystopian postcard from today’s Venezuela. The country is hobbled by years of polices that have decimated its economy, but reversing them requires adopting painful emergency measures. The government, which is desperately trying to hold on to power, has so far avoided them. Meanwhile, the servings on Venezuelans’ plates are getting paltrier. How long before they’re empty?

“The situation hasn’t improved and won’t improve in coming months because the government refuses to change its policies,” says Alejandro Gutiérrez, an expert in agriculture and food economics. “It will get worse.”

Where did all the food go?

Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro has blamed food producers (link in Spanish) and black-market dealers (Spanish) for Venezuela’s bare supermarket shelves. According to his theory, both are hoarding supplies for their own profit.

That explanation fails to address the reality that even before the current food crisis, local food production fell well short of what Venezuelans needed. The predominantly urban country—rural dwellers make up only 11% of the population, even lower than their 18% share in the US—has long relied on food imports, particularly of protein-heavy products such as meat and milk.

Hugo Chávez, Maduro’s predecessor, vowed to achieve food sovereignty. But the country’s food trade balance didn’t change much after he was elected in 1998. In fact, halfway into his tenure, Venezuela was importing more protein than before he took office.

That wasn’t an issue when Venezuela was dollar rich, thanks to the astronomical rise of oil prices during the Chávez years. Back then, it could buy whatever its people needed abroad. But now that oil is much cheaper, Venezuela’s foreign exchange reserves have dwindled. And the country is using the bulk of what remains to avoid defaulting on international debts rather than on replenishing its food pantry. Imports are way down.

Self-inflicted calamity

Venezuela’s diminished foreign exchange reserves are exposing the disastrous state of disarray of the country’s food industry.

Over the years, a series of Chavista polices, whose purported goals were to increase local food production and make it affordable for the poorest, have largely achieved the opposite, according to a study (Spanish) by Gutiérrez, a professor at University of the Andes in Venezuela.

Expropriations of industrial farms scared other growers from investing in land and equipment, and so did price controls that made their operations less profitable, says Gutiérrez. Even those wanting to expand plantings, or even just maintain them, have a hard time buying what they need, from fertilizers to tractors. Government-imposed currency controls make it hard to obtain US dollars to do that.

Meanwhile, output at the farms taken over by the government has been poor due to lack of technical knowledge and corruption, says Gutiérrez, despite the hefty state subsidies they’ve received. Overall, food production has sunk considerably in recent years.

Gutierrez’s analysis of government statistics shows that for practically every crop (Spanish), the number of kilos produced per Venezuelan has shrunk in the past two to three years. The processed food manufacturing industry had been similarly pummeled. Its per capita output decreased by an annual 3.5% from 2008 to 2015, Gutiérrez’s study shows.

And it’s not just food production that’s been upended. While supplies dwindle, Chávez’s policies, continued by Maduro, have pumped up demand. The same price controls that dissuaded farmers from planting more are encouraging black market dealers to clean out supermarket shelves. Then they sell the groceries at many times the official price, not only worsening shortages at legal stores, but stoking Venezuela’s already staggering inflation.

All this has led to a consequence unmeasurable in economic terms: the humiliation of Venezuela’s people, says Gutiérrez.

Out of reach

A big portion of the population has to queue for hours for a chance to buy a couple of packages of harina pan, the flour used to make Venezuela’s traditional food, arepas, or a few liters of oil at official prices. It’s not because there is no other food on sale, but because they can’t afford to buy anything that’s not kept artificially cheap by government controls.

If you have money, you can still find some food at supermarkets—ketchup, chorizo,cookies, cheese—middle-class Venezuelans say. You can also get harder-to-find products delivered from neighboring Colombia to your doorstep if you can pay in dollars, says Raúl Gallegos, senior analyst at risk-assessment firm Control Risks who recently travelled to Venezuela to evaluate the food situation. But the majority of Venezuelans, 87% according to a recent survey (Spanish, pdf), are too poor to buy enough food. Last year, the number of homes living in poverty (Spanish) grew by 53%.

The country’s basic household goods basket cost 24 minimum-wage salaries (Spanish) in June, up from 22 (Spanish) just two months earlier, and that’s taking into account a 30% bump (Spanish) in minimum wages in May. That’ll likely get even worse: the IMF is predicting inflation will reach 720% in 2016 and continue its dramatic rise in the foreseeable future, hitting 4,600% by the end of 2021.

Unhealthy diet

The nutritional value of the average Venezuelan’s diet has already taken a nosedive, according to the Venezuelan Observatory of Health, a research center associated with the country’s central university. Carbohydrates account for 75% of what they eat; the center calls it a “survival diet.”

There have already been some cases of deaths by malnutrition, says Marianella Herrera, the observatory’s director.

Among the most vulnerable are young children and pregnant women. A flagging healthcare system meant maternal mortality rates were already on the rise before food became scarce, but they’ve recently shot up, according to official data compiled by two Venezuelan doctors shows. (The government has stopped publicly releasing many key statistics, but continues to keep them and share them with certain healthcare professionals.) Maternal morality in 2016 will almost certainly be the highest its been in 50 years, according to projections by Julio Castro Méndez and Rafael Tineo Figueroa.

Malnutrition, which makes women more vulnerable to childbirth complications, is a factor in the spike, says Herrera.

A mother’s poor diet can also affect the health of her baby. There are no recent statistics for child mortality rates, but anecdotal evidence suggests it’s a growing problem. (Like maternal mortality rates, they started climbing well before the current crisis.) At a maternity hospital in Caracas 166 newborn babies (Spanish) died in the first six months of 2016, almost double in all of last year, local media reported.

Like with maternal mortality rates, undernourishment can’t fully explain the apparent increase in neonatal mortality this year, particularly considering the state of healthcare in the country. Medicine and key supplements for pregnant women, such as folic acid, are much harder to find than food. But not having enough to eat does play a role, says Herrera.

Hollow revolution

It’s an embarrassing reversal for a country that just last year received an award (Spanish) from the Food and Agriculture Organization for reducing hunger. While the degree of progress achieved under Chávez is contested by his opponents, it’s also true that poor Venezuelans had more to eat (Spanish, pdf) during his regime, as his adherents say.

What they don’t point out is that it wasn’t his caudillo-style socialism that fed the people, but the windfall that fortuitously landed on his lap when oil prices shot up. Indeed, funds for some of his touted food programs come directly from PDVSA, Venezuela’s national oil company.

Yet, even though the petrodollars that underpinned Chávez’s state-heavy economic model have dried up, Maduro and his supporters continue to cling to it. In fact, last month Chavistas celebrated what would have been Chávez’s 62nd birthday (Spanish,) vowing to defend his social policies.

Among the planned events were street marches and a concert of traditional Venezuelan music, in honor of el comandante‘s love of the genre. What they really should do is go to the zoo.

Correction (Aug 8): A previous version of this item inaccurately identified the firm Raúl Gallegos works for as Global Risk Analysis. It’s called Control Risks.