I remember the first time Harry Potter almost died, in a graveyard surrounded by a ring of Death Eaters. I remember when he almost died again, in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, after failing to defend himself against Voldemort’s killing curse. And I remember when Harry Potter truly died—at least figuratively—as the train to Hogwarts chugged away on the final page of the series’ final book, Harry and Ginny Weasley’s two sons on board.

Given the extreme success of Harry Potter, however, it’s not exactly surprising that the narrative didn’t really end with our protagonist’s progeny heading off into the sunset. At the end of 2007, Rowling released The Tales of the Beetle the Bard, the real-life version of a storybook that appears in the Potter series. And on Sunday, nearly 20 years after the first Potter book hit shelves, she returned with Harry Potter and the Cursed Child—Parts I and II, a stage play written by Jack Thorne based on a new story by Thorne, Rowling, and John Tiffany.

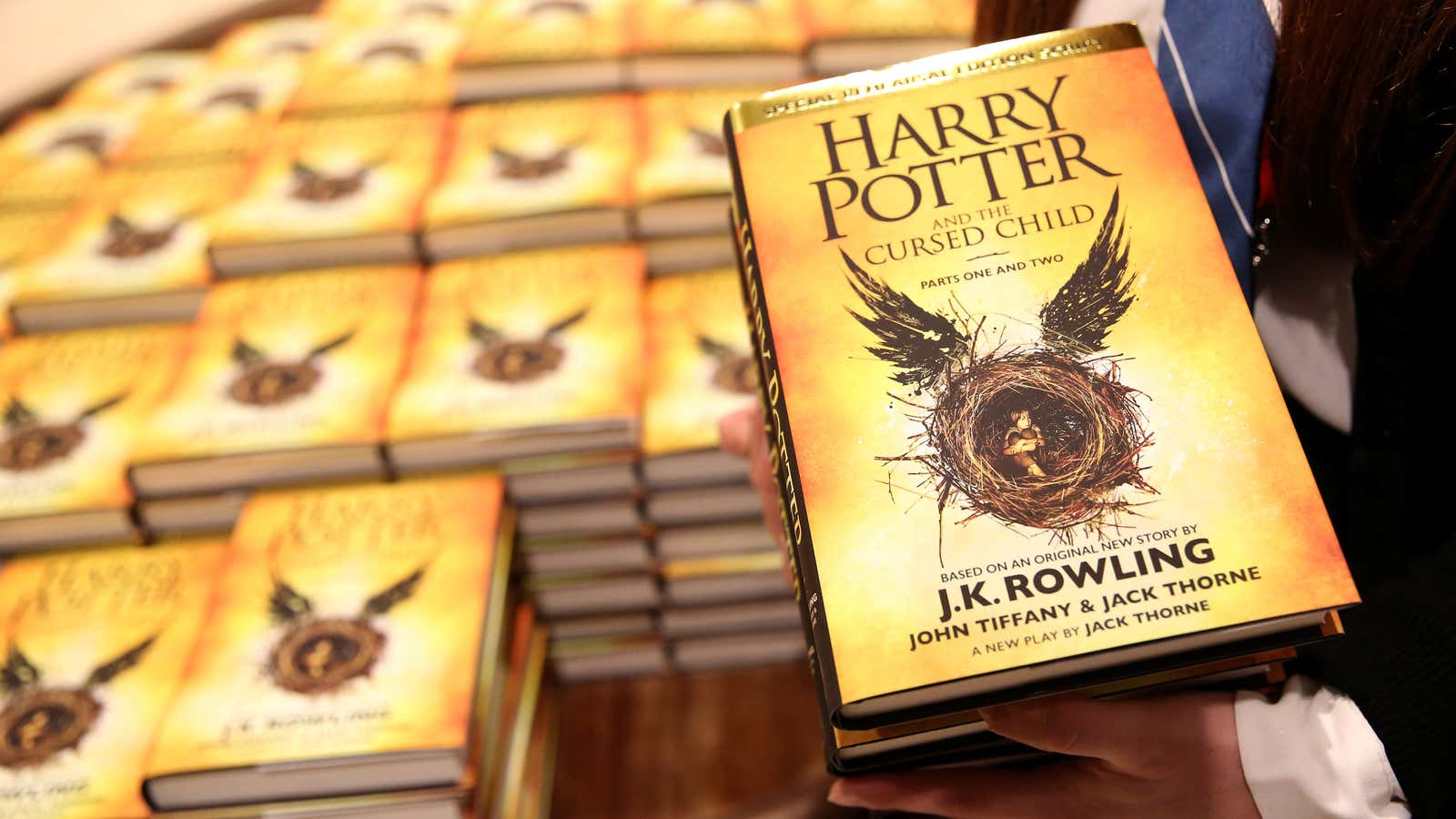

Already, Cursed Child is big—Potter big. As in the old days, fans lined up at bookstores before midnight on Saturday (July 30), and the book is already the top seller on Amazon. Yet despite having enjoyed some 15,000 pages of Potter books and 20 hours of Potter movies, I myself have no intention of reading Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, parts I or II.

This kind of resistance is out of character for me. When Deathly Hallows was released in 2007, I grieved like every other Potter fan. When the final movie was released four years later, I mourned the loss all over again. After all, the books had in some ways served as the defining cultural touchstone of my adolescence and young adulthood. I can still remember reading the early ones in my childhood bedroom, sneaking pages of the Half-Blood Prince at my college internship, and devouring Deathly Hallows the same day it was released, about two months after I’d moved into my first adult apartment.

As someone whose love of reading was informed by a childhood affair with books, JK Rowling was one of many authors to teach me that reading doesn’t have to be for school and doesn’t have to be hard. Together with the authors of The Babysitter’s Club, Goosebumps, and Are You There God? It’s Me Margaret, Rowling proved that reading can be an escape unto itself, a window into a world where goblins run banks or monsters live under kitchen sinks.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m sure the latest addition to the Potter oeuvre is fine; perhaps it’s even great. But there’s something about current cultural trends that suggests an unwillingness—on consumers’ part? On media executives’ part?—to move on. (For more evidence one need look no further than Hollywood, where Spiderman, Batman, and Superman have been dominating at the box office for decades, and Star Wars has become more brand than actual narrative.) Our collective inability to stop clamoring for more iterations of the same story suggests, either directly or indirectly, that everything popular and new is best made from something popular and old—sometimes not even that old.

At first glance, it seems possible (joy!) to blame this on millennials. The capabilities and import of technology have grown so exponentially in the average millennial lifetime that many young people seem to feel prematurely nostalgic.

“There is such an information overload that it has compressed their sense of time,” said Jamie Gutfreund, CMO at marketing agency Deep Focus, in an interview with Digiday. “Initially #tbt started off as a throwback to your childhood, but now, it’s throwback to last week.” Gutfreund calls the phenomenon ”early-onset nostalgia.”

This isn’t just marketing, but psychology. The country’s largest generation is still dealing with the after-effects of an economic recession, and the current effects of a highly partisan election cycle. Thinking about Pogs and Tamagotchis is a nice reprieve, and by that logic, Harry Potter is something of a safe space. But this tendency to use past success as an arbiter of merit is counterintuitive to cultural innovation.

Listen, I know it can be scary to let go. Admitting that you’ll never read another Harry Potter book is like accepting the end of a relationship. It might seem like you’ll never find another book series you’ll love this much. In moments of desperation, you may even go backwards, spending a lonely Sunday with an old favorite: maybe Prisoner of Azkaban or Goblet of Fire.

But for all the great things Rowling did for reading—and I would argue she did a lot—her most important contribution has been to change the stigma around young adult fiction. Since the Harry Potter books, YA has risen to a new level of prominence and respectability. There are more books, of greater variety, and many of them are being bought by adults. Which means there’s no better time to try something different.

Different doesn’t have to mean obscure, or even brand new. So just to get you started, here are five YA series worth a read:

The Hunger Games (3 books), by Suzanne Collins

Many people have seen these movies, but the Hunger Games is at its strongest as a book series. As engrossing as Potter, the trilogy also offers just-as-valuable life lessons about following your heart, knowing yourself, and avoiding bloodthirsty teenagers in good-versus-evil battle royales. And despite the popularity of the Jennifer Lawrence-lead film adaptions, Collins hasn’t even hinted at writing more.

Gone (6 books), by Michael Grant

Even though these books aren’t fantastically written, and contain elements of dubious supernaturalism, the Gone series—which kicks off with all of the adults in a particular town spontaneously disappearing—is a modern-day Lord of the Flies, complete with power-hungry toddlers and nuclear conspiracy theories.

The Magicians (3 books), by Lev Grossman

This trilogy isn’t technically young adult—it features cursing, drinking, and a bit of sex—but it hews so closely to the Harry Potter formula that I would be remiss to exclude it. Main character Quentin Coldwater is just a regular nerd dreaming of a bigger life when he finds himself suddenly thrust into a secret entrance exam for Brakebills, a hidden magic school in upstate New York.

Divergent (3 books), by Veronica Roth

The Divergent series has already been made into (woefully subpar) movies, but the books do a far better job of outlining Roth’s intellectual and moral questions, chiefly: What happens when you try dividing society into “factions” based on personality traits? (Sensing a theme? While not all young adult series are dystopian, it’s certainly common. See also: vampires.)

The Inheritance Cycle (4 books) by Christopher Paolini

If you’re done with Potter but in the mood for more mystical creatures, look into this trilogy by Christopher Paolini (who was just 14 when he started writing the first one). The books chronicle the adventures of Eragon, a boy who comes upon a blue stone in the forest that ultimately proves to be a dragon egg. Finders keepers.