Before there was Google, or Facebook, or YouTube, or even AOL, there was Tim.

Twenty-five years ago, on Aug. 6, 1991, someone asked a question on an internet forum. The response was the first public acknowledgement of the World Wide Web—the backbone on which all websites function, and the genesis of our modern internet culture and arguably the start of the digital communication revolution in which billions of people can now talk to each other, access any piece of information or order pretty much anything they want instantaneously.

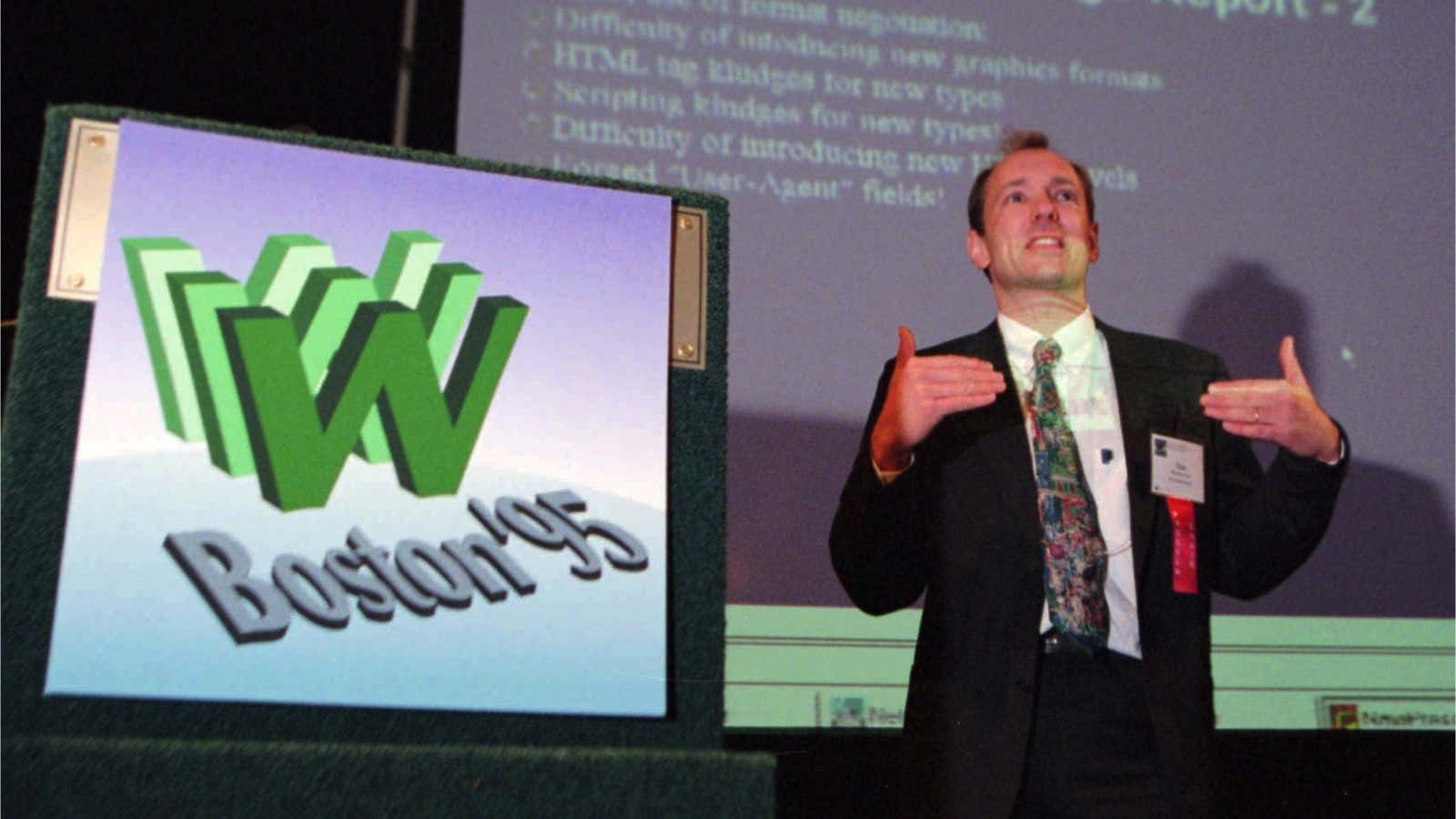

The first website, which was literally a website explaining what a website was, went online in November 1992. It was created by Tim Berners-Lee, at the time a researcher at CERN (the European Organization for Nuclear Research). But before the site went live, Berners-Lee brought up the project he was working on—hyperlinks, the technology that allows pieces of information to be linked to each other on the internet—on a Usenet page. Usenet was a pre-web forum when just a couple million people were on the internet; its archives have since been acquired by Google. If you want to find the first rumblings of the modern web online now, you have to trudge through some incompletely archived pages on Google Groups.

Berners-Lee was responding to a question someone asked about whether anyone knew anyone working on the concept of hyperlinks. As one of the people directly working on that exact topic he seemed perfectly situated to respond. Here’s what he said:

The WorldWideWeb (WWW) project aims to allow links to be made to any information anywhere. The address format includes an access method (=namespace), and for most name spaces a hostname and some sort of path.

We have a prototype hypertext editor for the NeXT, and a browser for line mode terminals which runs on almost anything. These can access files either locally, NFS mounted, or via anonymous FTP. They can also go out using a simple protocol (HTTP) to a server which interprets some other data and returns equivalent hypertext files. For example, we have a server running on our mainframe (http://cernvm.cern.ch/FIND in WWW syntax) which makes all the CERN computer center documentation available. The HTTP protocol allows for a keyword search on an index, which generates a list of matching documents as annother virtual hypertext document.

If you’re interested in using the code, mail me. It’s very prototype, but available by anonymous FTP from info.cern.ch. It’s copyright CERN but free distribution and use is not normally a problem.

The NeXTstep editor can also browse news. If you are using it to read this, then click on this: <http://info.cern.ch/hypertext/WWW/TheProject.html> to find out more about the project. We haven’t put the news access into the line mode browser yet.

We also have code for a hypertext server. You can use this to make files available (like anonymous FTP but faster because it only uses one connection). You can also hack it to take a hypertext address and generate a virtual hypertext document from any other data you have – database, live data etc. It’s just a question of generating plain text or SGML (ugh! but standard) mark-up on the fly. The browsers then parse it on the fly.

The WWW project was started to allow high energy physicists to share data, news, and documentation. We are very interested in spreading the web to other areas, and having gateway servers for other data. Collaborators welcome! I’ll post a short summary as a separate article.

Other than dated references to things like the NeXT computer system (the computer and company Steve Jobs developed after getting booted from Apple in 1985 before returning in 1997) and calling the web the “WorldWideWeb” as one word, what’s interesting here is how Berners-Lee envisioned the web being used. He saw it as a place that academics could share information, rather than a place that reality TV celebrities could worry about what phone to get next, or where multibillion-dollar corporations could spring up to categorize and sell advertising against all of its content.

Berners-Lee followed up with a little more information on how hyperlinking would actually work:

The WWW project merges the techniques of information retrieval and hypertext to make an easy but powerful global information system.

The project started with the philosophy that much academic information should be freely available to anyone. It aims to allow information sharing within internationally dispersed teams, and the dissemination of information by support groups.

Reader view

The WWW world consists of documents, and links. Indexes are special documents which, rather than being read, may be searched. The result of such a search is another (“virtual”) document containing links to the documents found. A simple protocol (“HTTP”) is used to allow a browser program to request a keyword search by a remote information server.

The web contains documents in many formats. Those documents which are hypertext, (real or virtual) contain links to other documents, or places within documents. All documents, whether real, virtual or indexes, look similar to the reader and are contained within the same addressing scheme.

To follow a link, a reader clicks with a mouse (or types in a number if he or she has no mouse). To search and index, a reader gives keywords (or other search criteria). These are the only operations necessary to access the entire world of data.

Information provider view

The WWW browsers can access many existing data systems via existing protocols (FTP, NNTP) or via HTTP and a gateway. In this way, the critical mass of data is quickly exceeded, and the increasing use of the system by readers and information suppliers encourage each other.

Making a web is as simple as writing a few SGML files which point to your existing data. Making it public involves running the FTP or HTTP daemon, and making at least one link into your web from another. In fact, any file available by anonymous FTP can be immediately linked into a web. The very small start-up effort is designed to allow small contributions. At the other end of the scale, large information providers may provide an HTTP server with full text or keyword indexing.

The WWW model gets over the frustrating incompatibilities of data format between suppliers and reader by allowing negotiation of format between a smart browser and a smart server. This should provide a basis for extension into multimedia, and allow those who share application standards to make full use of them across the web.

This summary does not describe the many exciting possibilities opened up by the WWW project, such as efficient document caching. the reduction of redundant out-of-date copies, and the use of knowledge daemons. There is more information in the online project documentation, including some background on hypertext and many technical notes.

Try it

A prototype (very alpha test) simple line mode browser is currently available in source form from node info.cern.ch [currently 128.141.201.74] as

/pub/WWW/WWWLineMode_0.9.tar.Z.

Also available is a hypertext editor for the NeXT using the NeXTStep graphical user interface, and a skeleton server daemon.

Documentation is readable using www (Plain text of the installation instructions is included in the tar file!). Document

http://info.cern.ch/hypertext/WWW/TheProject.html

is as good a place to start as any. Note these coordinates may change with later releases.

What started out as a way of connecting researchers, in much the same way that the internet itself started out as a way of connecting universities (and military facilities), has ballooned over the last 25 years into the most important communication tool since the Gutenberg press. Sadly, most scientific research papers are not freely available online, but at least I can easily tell you which type of cookie you are, or which fast-food chain best represents you.

So there’s that.