A mysterious star has attracted global attention since its strange properties came to light in October last year. The star showed an odd pattern of dimming that could not be explained by any known natural phenomenon. Among the hypotheses that has yet to be disproved: the star is surrounded by an alien megastructure.

Such extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, as the famous astronomer Carl Sagan put it. Ever since Tabetha Boyajian of Yale University found KIC 8462852, or Tabby’s star (named after her), professional scientists and amateur astronomers have been pointing their telescopes towards a small part of the night sky to collect more data.

A flurry of studies published over the past year show that the more data scientists collect, the stranger the star’s tale becomes. Every attempt to rule out the alien-megastructure hypothesis is met with more data that stops it from being discarded.

The sign that started it all

NASA launched the Kepler mission in 2009. Its aim was to search for planets by fixing its gaze at a tiny patch in the sky. When it spots a star’s light suddenly dim, it means that a planet has crossed between the star and the satellite. The amount of dimming is related to how big the planet is.

This is monotonous work. NASA created software to interpret the dimming—planets orbiting a star dim the light at regular intervals, so the agency’s software flagged these episodes to scientists to confirm the readings. A contingent at Yale, meanwhile, launched a website called Planet Hunters, where amateur astronomers, citizen scientists, and other enthusiasts could also access Kepler’s data, helping NASA identify more planets.

Though Kepler’s software helped identify more than 2,000 planets around more than 1,000 stars, there were things that it missed. The Planet Hunters site helped discover dozens more planets and interesting stars—most importantly, one of them was KIC 8462852, first flagged by citizen scientists in 2011.

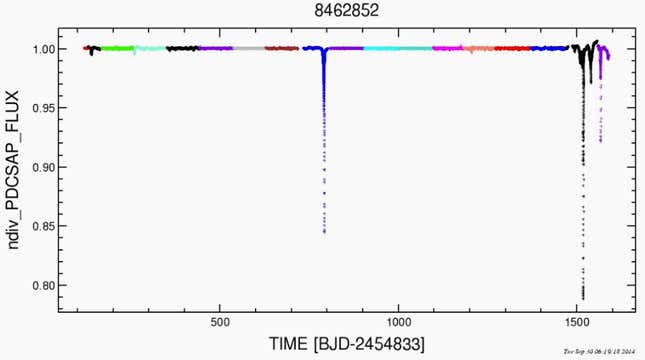

It was the chart above that caught amateur astronomers’ attention. The chart shows data collected over 1,500 days of observation (showed on the x-axis). Each dip on the y-axis is a dimming event. Although these dips would normally indicate the presence of a planet, the weird thing about KIC 8462852’s dimming is how big it is. At its largest, it shows the star dimming by more than 22%, which is 10 times bigger than the dimming observed by a Jupiter-sized planet crossing a similar-sized star. Thus, it seems likely that the dimming wasn’t caused by a planet, but something else.

Star wars

Boyajian and her colleagues shared these results with other astronomers. The title of their paper was “Where’s the flux?” and she dubbed it the WTF star. Soon, many more began investigating the mysterious star.

But no sooner was an hypothesis suggested as data was produced to shoot it down. As Quartz reported previously:

The hypotheses they eliminated: The star could be surrounded by cloud of dust… but it is too old to have such a planet-forming disk. A collision of planets could have caused the formation of a thick layer of debris… but such an event is too brief in cosmological timescales to be spotted by human telescopes. Finally, there could be a swarm of comets creating the shade… but calculations show the dimming is far too much to be explained by comets alone.

So was it aliens? The theory behind the hypothesis is simple. Again, as Quartz put it:

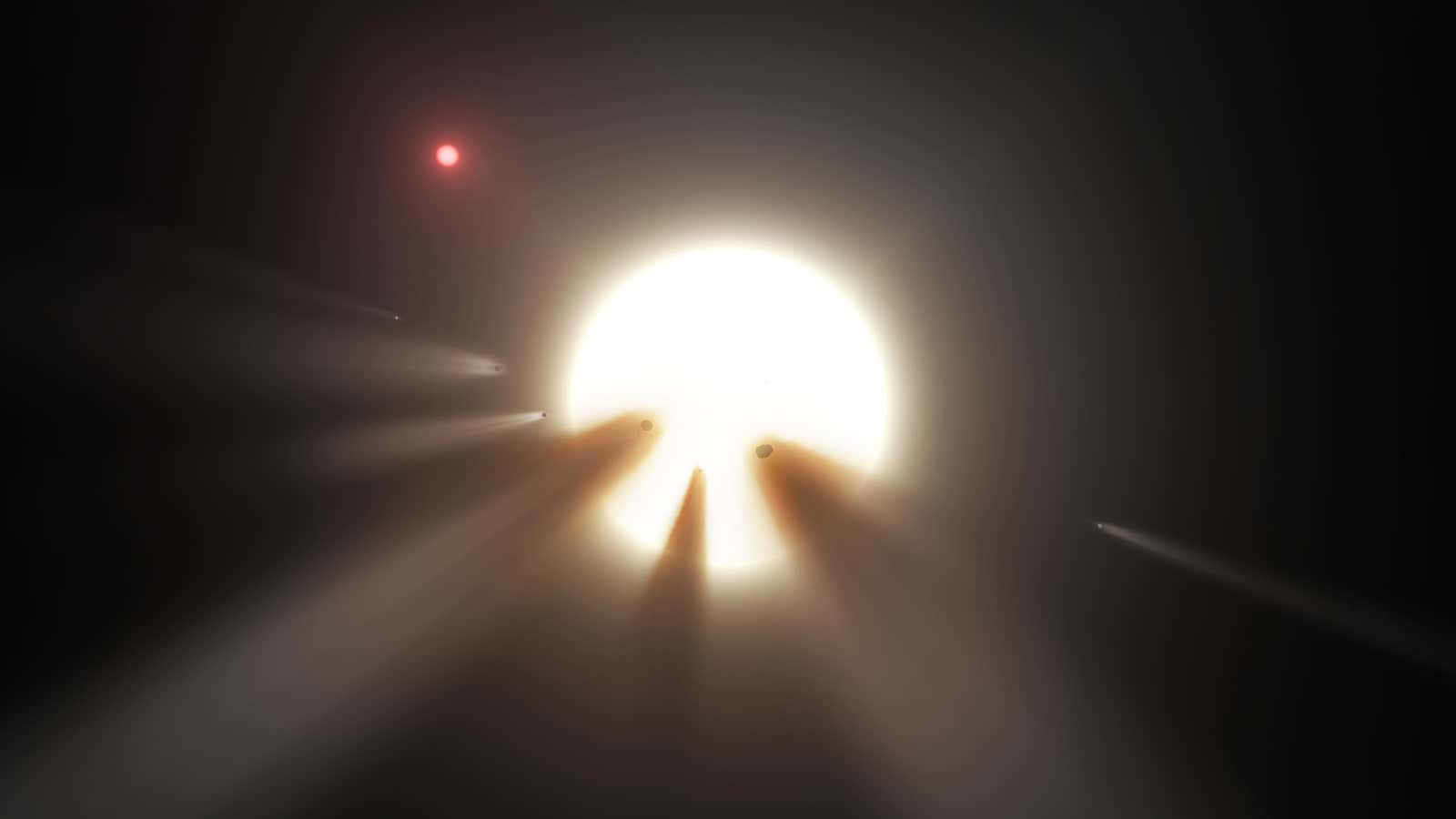

In the 1960s, renowned physicist Freeman Dyson argued that the energy demands of any intelligent race would, within a few millennia using advanced technology, outstrip whatever supply were available on the planet. In that case, the most effective way to start capturing more energy would be to build a solar-panel contraption to capture its star’s light. Such a structure would start small, but in theory eventually cover the whole star, in what is now called a “Dyson sphere.”

The SETI Institute has taken particular interest in the star. After all, SETI stands for Search for Extra-terrestrial Intelligence.

Last year, the institute paused its other searches and pointed their radio antennae towards Tabby’s star for two weeks. They hoped to detect a microwave signal that is thought to be the most likely sign of an intelligent civilization. After two weeks of intense staring, however, SETI scientists found nothing. This does not rule out alien life, but it means that SETI can’t spend more of its resources looking at a single star unless there is more compelling evidence to do so.

Brad Schaefer of Louisiana State University thought he had found it. Kepler looked at Tabby’s star only for a few years, but Schaefer knew that astronomers had been photographing that part of the sky for more than a century. Many of these photographic plates were digitized and available for analysis. When he looked at the data for Tabby’s star, he found that over the past century light output from the star itself had dimmed by nearly 20%.

Like with the Kepler data, there were no natural hypotheses to explain the long-term dimming of this particular star. But then, like before, other scientists came forward to poke holes in Schaefer’s analysis. They suggested that what Schaefer was observing was simply the result of the “hodge-podge nature of the photographic plates” used for the analysis.

Where are the aliens?

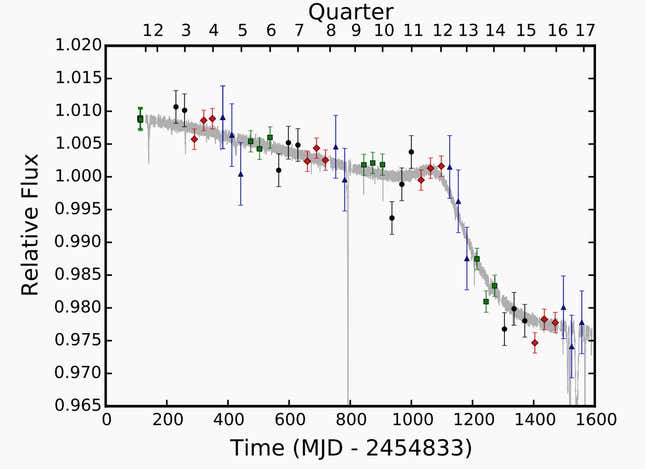

To Schaefer’s chagrin, many astronomers agree that his analysis might indeed be flawed. But a new analysis has fanned the flames on the controversy. Astronomers from California Institute of Technology and Carnegie Institute published a paper, which is yet to be reviewed, showing that, apart from the occasional dimming that Kepler observed, the long-term trend shows the star’s total light output is also declining rapidly, as suggested by Schaefer. The rate of decline over the Kepler observation period is in fact twice what Schaefer estimated over the past century, the paper suggests.

Could aliens have been building the Dyson sphere over that time? It’s possible. Schaefer’s analysis may be in doubt, but Kepler’s data is not. And, yet, we don’t have enough data to say whether the weird behavior of Tabby’s star is explained by alien megastructures or some other as-yet-unknown natural phenomenon.

Astronomers aren’t giving up on solving the mystery. In a recent Kickstarter campaign, the WTF team raised $100,000 to buy time on a private network of telescopes that will let them watch the star for at least two hours every night for a year. Expect more news, and intrigue, soon.