Exactly like climate change keeps bringing more droughts and floods, the way news is consumed on social will lead to greater instability and accidents—and collateral damage to democracy.

For news, this is the perfect storm. It combines the triumph of superficiality over depth and substance, the acceleration of the news cycle, the decline of media that used to provide necessary checks and balance and, for good measure, the spectacular economic imbalance between new and old media players.

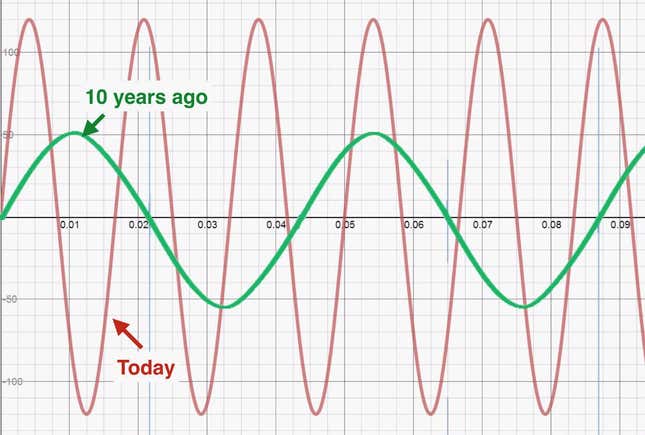

If the evolution of the news cycle could be summed up in one graph, it would look like the sinusoid below. The amplitude reflects intensity (how we champion or we tear down people or causes, and the wavelength represents the news cycle’s time span or density:

The green line shows a relatively slow cycle. For news, ten or 15 years ago the main accelerator was live television. That was it. The rest of the journalistic crowd was free to dig deeper, to take the time to put things in perspective and provide informed analysis. Legacy media enjoyed a large audience in print and online. Even digital newcomers such as Salon (1995), Slate (1996) or, later, Politico (2007) practiced a fairly classic kind of journalism that unfolded in a longish cycle. Investigation still meant something—whether it covered public interest issues, fed the democratic debate, or held elected officials accountable. It was not unusual to see a news organization spend $50,000 or $150,000 to fund an “enterprise journalism” project. For the good, rather than the worse, media were in control of the news cycle’s sinusoid—both amplitude and wavelength.

The red curve tells a different story. Combining mobile access with the social tsunami, news consumption habits are now very different. The news cycle has become faster, denser, and with a greater amplitude. Today, we love and hate at a much faster pace than ever before, and with more intensity. As the media time span is compressed, the wavelength is shorter, with a greater amplitude. More pinnacles and more pillories fit in a much shorter time span.

The Brexit accident and the rise of Donald Trump provide the perfect illustration of this fundamental alteration of the news cycle.

Media that once could take their time to do their job suddenly had to deal with a new breed of competitors. Scores of new media outlets—lighter, more agile, and many profusely funded—were changing the game by operating under their own directive: the obsessive search for more clicks. That quest resulted in pernicious side-effects, including the drive to produce large quantities of shallow, superficial pieces. News was aimed at being snacked, not read.

Two factors made things even worse. The first was the reaction of legacy media, which was too slow to take the full measure of the situation. They failed in multiple ways: they didn’t invest sufficiently and quickly enough in critical technologies; they didn’t listen to their young readers; they couldn’t create new products; and were unable to reduce their costs in order to fight competitors who had the advantage of starting from a blank slate.

More importantly, they failed at reforming their internal culture (see this previous Monday Note).

That being said, no drastic measure could have prevented shifts in the fundamentals of news consumption. As an example, see how losses threaten the print sector when its ad spending gradually adjusts to the actual time spent by readers (unfortunately, it’s not the other way around—more money poured into ads doesn’t result in readers spending more time).

As new digital players joined the fray, loaded with venture capital money and a license to incur whatever losses were necessary to capture market share and achieve dominance, legacy media found themselves on their heels. Economically unable to preserve the integrity of their key assets—the ones that used to make the difference between commodity and value-added news—they lost their ability to fortify their element of differentiation: their editorial quality.

Over the last ten years, newsrooms in the United States have lost about 40% of their workforce. (Incidentally, this unprecedented depletion came to benefit the whole communication sphere: corporations became content producers, media needed professionally made branded content, and all them hired former writers and editors en masse.)

Then we had three converging factors: a growing audience gap (users, time spent) between old and new players; a shift in the news format that favors short, commoditized, click-bait oriented pieces of information powered by social; and the rise of mobile that further accelerated the format shift.

In conclusion, legacy media lost on both ends: They no longer have the resources to provide effective checks and balances, and they lost the audience battle anyway.

Truth and lies about video

Today, the upcoming dominance of video is the talk of the town. Allow me a grain of skepticism.

First, glowing promises for video consumption come from actors with a strong economic agenda: Facebook; internet providers and network suppliers such as Verizon, or Cisco; and producers of video-oriented apps like Periscope, Facebook (again), or YouTube. Each of these players has a vested interest in inflating numbers, either because they can charge more, or because they will sell more gear or bandwidth.

Second, there are two kinds of videos: the ones designed for social use such as NowThis (two billion video views per month on Facebook) and AJ+ (four billion), and longer formats seen on YouTube or on legacy media.

As for Facebook, the stunning “video-streamed” numbers must be taken with great caution: Facebook tends to vastly overestimate the view counts for videos that, in fact, play automatically—meaning they are not requested by users. In addition, the social network acts as a copyright terminator with more than 70% of its most popular segments being, in fact, stolen. Therefore, while YouTube might be a true enabler for video producers, Facebook is more into the business of recycling stolen items. (For more on Facebook practices, read this compelling piece by YouTube producer Hank Green.)

When it comes to news, the death of text has been greatly exaggerated.

The recent Digital News Report published by the Reuters Institute highlights an interesting view (emphasis mine):

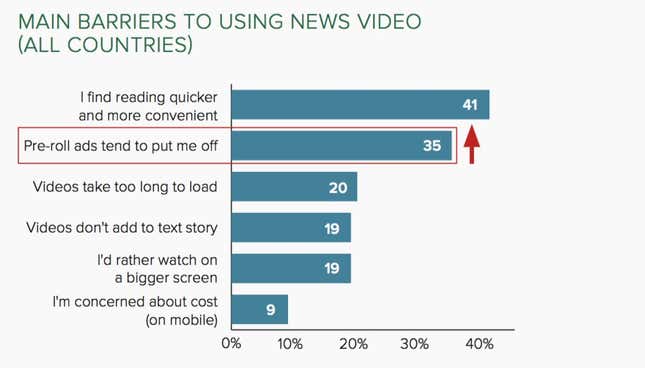

Across our entire sample [from 26 countries], the vast majority (78%) say they only read news in text or occasionally watch news video that looks interesting. Just one in twenty (5%) say they mostly watch rather than read news online. When pressed, the main reason people give for not using more video is that they find text quicker and more convenient (41%). Around a fifth (19%) say that videos often don’t add anything to what is already in the text story.

When asked in the survey: “You said that you don’t usually watch news videos online. Why not?” respondents give the following reasons:

It is therefore fair to say that the rise of video will: (a) mostly be driven by, and benefit social media and, (b) mostly promote very short formats: closer to 30 seconds than one minute.

As a consequence, media organizations that used to provide quality-oriented information are losing the race for digital advertising dollars.

As recent earnings show, we see great established media outlets such as The New York Times or The Guardian reporting actual declines in their digital advertising revenue while, at the same time:

- Digital ad spending is expected to grow by 12% this year (PwC), and

- Facebook and Google are raking in 85 cents for every dollar spent in digital advertising in the US market, with Q2–16 worldwide year-on-year growth of respectively.

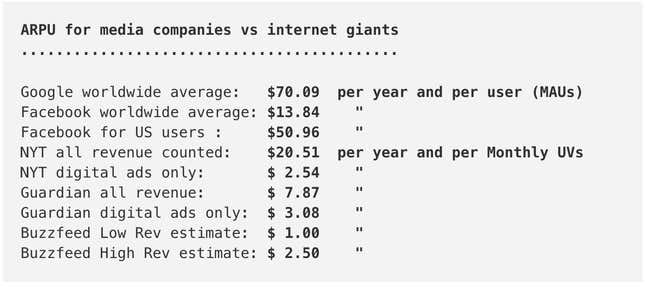

Let’s now consider two other metrics: the respective ARPUs (Average Revenue per User) and the VaPU (Valuation per user) (original Google Sheet is here):

To put it another way, when it come to digital ad revenue, Google makes 27 times more than The New York Times or Buzzfeed under its best 2016 revenue hypothesis of $500 million. As for the Guardian, Google makes 22 times more. Note that The New York Times gets its real ARPU from its 1.4 million digital subscribers who bring individually about $160 each year—that’s the virtue of paying subscribers in case anyone doubts it.

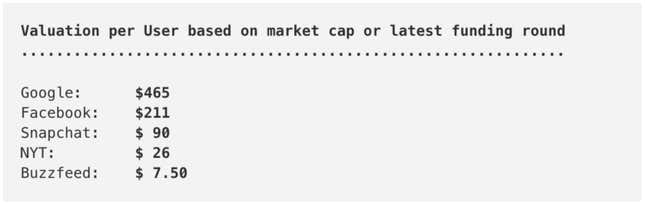

When looking at the valuation of each company’s users (again, based on MAUs and UVs—Monthly Active Users and monthly Unique Visitors):

Each of Google’s 1.17 billion MAUs are valued at 2.2 times Facebook’s, 18 times the Times’, five times Snapchat’s (with a staggering $18 billion valuation), and 62 times Buzzfeed’s, with a more “reasonable” $1.5 billion valuation.

For the news industry, this huge economic gap carries two likely consequences: internet giants and digital native news outlets will have tremendous financial firepower to do whatever it takes in terms of marketing or their ability to go further into the general information segment (cf. Snapchat), and the network effect will apply even further when advertising dollars dry up for what will be increasingly seen as niche media.

More broadly: Except for the old, educated, and affluent segment of the population, the vast majority will be informed by a rapid-fire of superficial and shallow contents spat by the social firehose. Expect more Brexit hurricanes and Trump floods in the future.