Facebook’s newest app made it really easy for us to pretend to be high schoolers.

Last week, Facebook launched a new app, called Lifestage, which lets users publicly share information about their lives. It seems to be an odd amalgamation of Yik Yak, an anonymous college-focused social media app, and Snapchat, the popular messaging and photo sharing app.

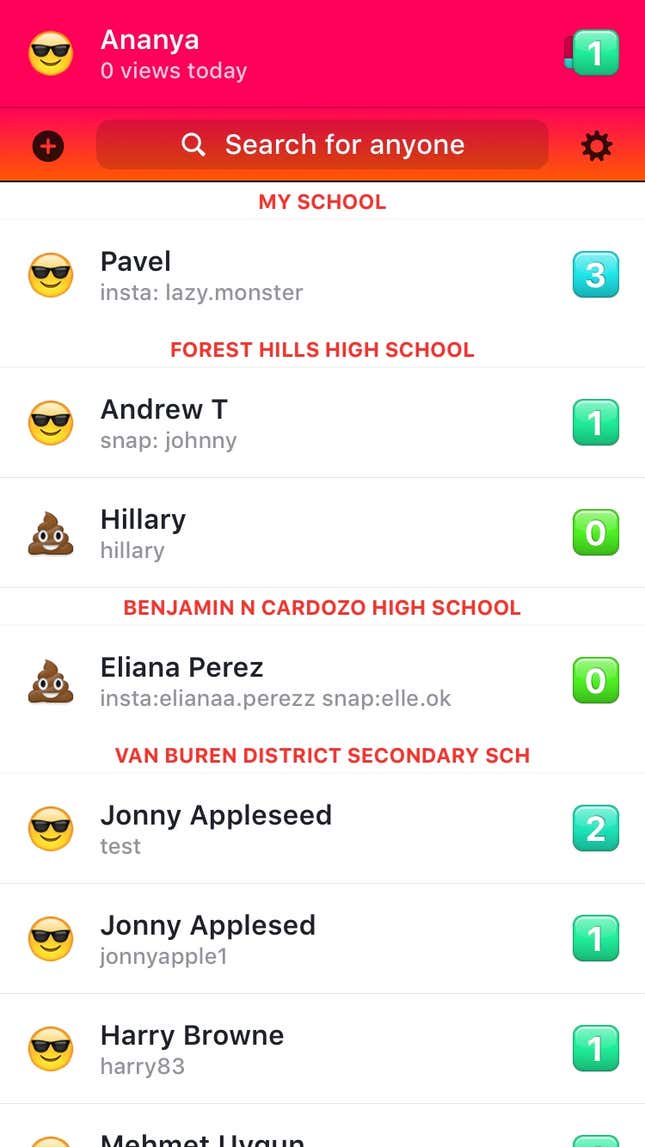

Focused on teens, Lifestage lets you only connect to your high school, and share videos of things you like, dislike, people, and reactions, as well as videos from school, home, food, and people. There’s no messaging on the app, so you can’t interact with anyone directly. But unlike with stories on Snapchat, everything shared on Lifestage can be viewed by anyone who says they attend a specific high school.

Lifestage may seem like an overt attempt by Facebook to attract more teens—a demographic it’s been searching to shore up for years, especially after Snapchat turned down a reported $3 billion to join Facebook in 2013—but there are also some worrying privacy concerns.

The authors of this post are 24 and 29 years old, respectively, which some would say is too old to be in high school. Yet, we easily signed up as 17-year-olds and joined the Brooklyn Technical High School and Manhattan Business Academy networks. Other colleagues joined other high schools just as easily. We could see videos posted by high school students, even from locations hundreds of miles away. We’re in Manhattan, but we saw videos from high schoolers in Miami and other schools across the US.

Beyond confirming your cell phone number, there is not much of a verification process with Lifestage: Anyone can lie about their age or school. In the early days of Facebook, you needed to provide a “.edu” email address to prove that you attended a specific high school or college. Now, anyone can say they attend any institution. If high schoolers—or anyone else—don’t want strangers seeing their photos, videos, and posts, they can set their Facebook profiles to private. On Lifestage, everything published to the app is public to anyone that joins the network. Lifestage also suggests its users include links to other social apps, such as Instagram and Snapchat.

We were merely testing the limitations of the app’s signup process, but someone with more malicious intentions could easily do the same thing we did. The app seems to acknowledge the issue. One of the screens during the signup page explains that ”Everything posted is public. Audience cannot be limited in any way. We can’t promise that anyone in a school actually goes to that school.” It’s just whether its younger users will heed that information, and realize that whatever personal, intimate moments that they would share on a service like Snapchat would be far more public if shared on Lifestage.

Questioning whether it considered that over-age users could lie about their age and use the app, a Facebook representative told Quartz:

We are releasing Lifestage to a limited number of high schools. Lifestage will not provide access to content from other people for users who list an age above 21. We encourage anyone using the app who experiences or witnesses any concerning activity to report it to us through the reporting options built into the app. We take these reports seriously. Unlike other places on the web, Lifestage is tied to a person’s phone number and only one account is allowed per phone number – this provides an additional level of protection and enforcement.

In February 2016, a BBC investigation showed pedophiles used Facebook to pass around lewd photos of children, through secret groups with explicit names, some even administered by convicted sex offenders. At the time, the UK’s children’s rights commissioner Anne Longfield told the BBC, “I’m shocked those don’t breach community standards, any parent or indeed child looking at those would know that they were not acceptable. I don’t think at the moment, given what we know about the vulnerability of so many children to predators, that [Facebook is] doing enough.”

Given Snapchat and Instagram’s popularity, it’s difficult to see why a teen would jump from those services for a product like this, and judging from the lack of content on the app, it doesn’t look like many are. Fast Company writes that Lifestage’s strategy seems to be a bet that teens want to show off all different aspects of their life to the public, like to Snapchat’s Stories section. But users can also send private messages on Snapchat, and any Stories content you post isn’t automatically broadcasted to every single Snapchat user. (You can submit a photo or video to a Snapchat-curated Live Story, which is available to everyone, but that’s not automatically selected.)

Yik Yak is also similar to Lifestage, in that both organize their users by which school they attend. But, Yik Yak is anonymous, nor does it ask for Instagram or Snapchat handle, like Lifestage does.

Many Facebook apps spring into life and die a quiet death in obscurity soon after, with Facebook suggesting that many of these apps are built and deployed to test out features that may well end up in one of its core products. Suffice to say, it’s difficult to see what part of Lifestage might end back up in Facebook.com.