China launched its first Tibetan-language search engine this week, called Yongzin. It aims to be a “unified portal for all major Tibetan-language websites in China,” according to the state news agency Xinhua.

Yongzin means “master” or “teacher” in Tibetan. It is the world’s first search engine solely in the Tibetan language, and also the one and only choice for China’s seven million Tibetan people, unless they use a VPN to jump China’s Great Firewall. Chinese search engines like Baidu and Sogou don’t search in Tibetan, while Google, which does, has been blocked in China for years.

Yongzin features sections for news, images, videos, and music just like Google, and even has a logo with similar colors and designs to Google’s, which was quickly noticed.

The search engine is a product of a state-funded project which began in April 2013 and cost 57 million yuan ($8.7 million). Of the some 150 developers, more than 80% are ethnic Tibetans. It is expected to eventually gain 2 million users in China, Xinhua said.

The Chinese government wants the service to act as a propaganda tool too. In the future, Yongzin will provide data for the government to guide public opinion across Tibet, and monitor information in Tibetan online for “information security” purposes, Tselo, who’s in charge of Yongzin’s development, told state media (link in Chinese) at Monday’s (Aug. 22) launch event.

Quartz contacted several Tibetan speakers and asked them to put Yongzin to the test. Perhaps not surprisingly, search results vary widely between Google and Yongzin.

Searching “Free Tibet” in Tibetan on Yongzin brings up a 2014 People’s Daily article about “illegal publications” related to Tibet and Xinjiang independence as the top result, a researcher from London-based NGO Tibet Watch who wished to remain anonymous, said. The same search on Google shows results about several Tibetan advocacy groups.

A search for “the Dalai Lama” in Tibetan on Yongzin doesn’t show the Tibetan spiritual leader-in-excile’s official website, the researcher noted. The same search on Google brings it up in the first five search results. “None of the top results [on Yongzin] are particularly relevant,” the researcher said.

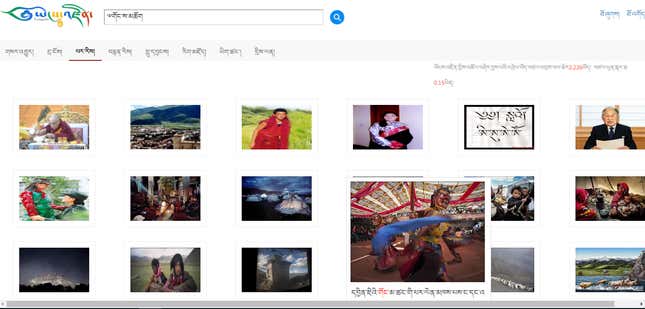

The same search using the “Images” tab on Yongzin shows only one photo of the Dalai lama from a defunct site among 20 images. Google Images shows an infinite number of photos of the Dalai Lama, the researcher noted.

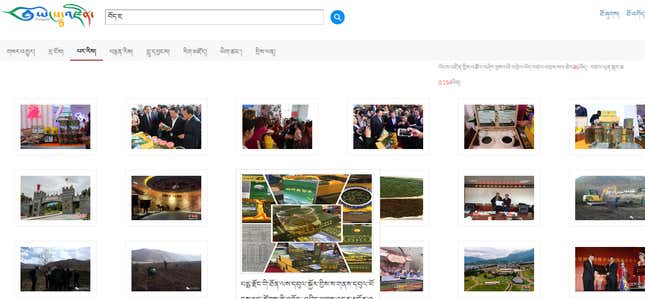

Even more innocuous terms like “Tibetan tea” appear to be censored. Searching for the term on Yongzin’s image search yields mostly photos of Chinese officials drinking tea.

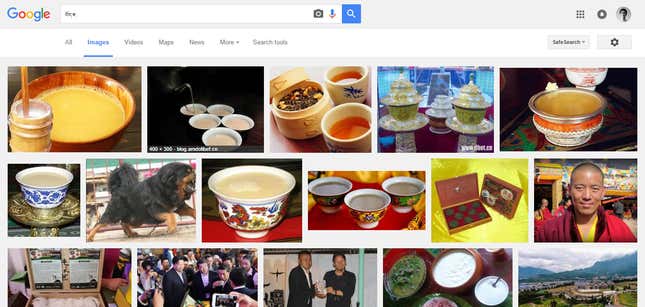

On Google, however, it brings up photos of actual tea from Tibet.

Tibetan advocates say China continues to tighten control over the ethnic Tibetan people inside the country, including their embrace of Tibetan. In March, a Tibetan entrepreneur was charged with inciting separatism for advocating bilingual education in schools across China’s Tibetan regions.

“The main political effect of this initiative is that it allows China’s government to position itself as a defender of Tibetan culture and heritage,” Alistair Currie, a spokesperson with London-based advocacy group Free Tibet said. “However, as with everything in Tibet, language is tainted with political connotations, and Beijing wants to control any development rather than allow it to flourish uncontrolled.”

There is a growing number of blogs, websites, and social media in Tibetan originating from Tibet, Currie said, but none of it is accessible through the new search engine.