When you purchase a book from a bookstore your rights to that particular stack of paper are pretty intuitive. It becomes your personal property, not much different from a t-shirt, a diamond ring, or anything else you might carry around. You can sell your book, lend it to a friend, or toss it in the fireplace. In short, unless you’re making a copy, you can do whatever you want without asking for permission from the book’s creator.

Those intuitions about ownership fall apart when we talk about our digital things. Some of the differences are obvious: You can’t line up your ebooks on a shelf, scribble notes in the margins, or lose them under your bed. But if you are like most consumers you are probably unaware of the more subtle ways that your digital books—and movies, games, and other media purchases—are different from physical copies. That’s because your rights to those digital things are filtered through a maze of intellectual property law and limited by the fine print that you agree to when you buy them.

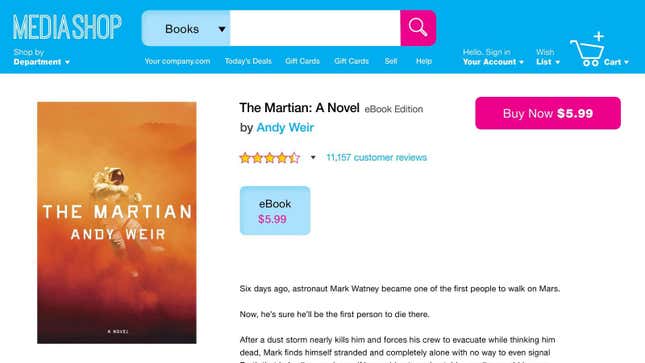

To measure the gap between what consumers believe and what rights they actually get, two legal scholars, Aaron Perzanowski and Chris Jay Hoofnagle, created a fake ecommerce site called “Media Shop”. The authors studied the behavior of hundreds of online shoppers and published their findings in a paper called “What We Buy When We Buy Now”(pdf). Before I tell you what they learned, I’ll give you a chance to test your knowledge by answering similar questions to ones they posed.

Consider the following screenshot, which offers an ebook of The Martian, and then answer the questions below.

Giving up on ownership

When you purchase an ebook you must agree to the Terms of Service (TOS) that tell you what you can do with it. TOS are essentially very one-sided contracts written by the company selling the digital goods. Often they include provisions that shield the business from liability and even prevent the consumer from going to court if they feel ripped off. Typically a consumer’s only choice is to accept them as they are, or to decline to use the service entirely. An overwhelming majority of internet users agree to them without reading them. In one experiment 98% of users failed to notice a clause requiring them to give up their first-born as payment.

Using contracts to make an end-run around property law predates the web. When the first wave of digital goods—software—began to appear in the 1970’s, businesses devised standardized End-User License Agreements (EULAs) as a legal hack to prevent users from copying their products. Unlike other kinds of property, software could be copied instantly with almost no effort. Rather than wait around for courts to figure out how to protect their business model, companies stopped selling software altogether and instead began to license it. Licensing contracts provided software businesses with a tool to control what the buyer did with their software, without the overhead of negotiating terms with each customer.

Since then the world of digital goods has exploded. We now routinely license books, movies, music, and games in addition to software. Decades have passed since the first software licenses were stuck onto floppy disks, but the actual law remains largely the same. Licensing agreements have been supplemented by far more pervasive TOS contracts, which extend similar protections to websites and other services. Consumer protections have, if anything, gotten weaker. People who were once owners have been transformed into mere users.

At the same time, software itself has penetrated every part of our lives. It has become an essential component of many things we are used to thinking of as physical objects. As Perzanowski and co-author Jason Schultz put it in their forthcoming book, The End of Ownership, “Your car is a computer with wheels; a plane is a computer with wings; your watch, your child’s toys, even your pacemaker are all computers at their core.” You may own your car but the software required to drive it is more like a song you listen to while driving, it’s only licensed to you.

Tractors, vibrators, and other new frontiers

As the things we buy—and create—are increasingly digital, the question of what we actually own is bubbling up in unexpected places.

Owners of John Deere tractors discovered that they can’t legally fix their own equipment, because according to the company, the buyer only acquires “an implied license for the life of the vehicle to operate the vehicle.” Those terms prevent third-party mechanics from using diagnostic software to determine why the tractor is broken, effectively making it impossible to repair. As a result, no matter how capable a farmer’s local mechanic might be, he has no choice but to take his tractor to John Deere’s own, often much more expensive, certified mechanics.

Contracts designed to protect software often also grant the company the right to do things that seem to invite abuse. For example, in 2009 Amazon remotely deleted copies of George Orwell’s 1984 from customers’ Kindle readers. If doing this had required them to physically enter each customer’s house, it would have clearly been a crime, but under the Kindle Store terms of service their action was entirely legal. In similar fashion, video game companies have knowingly broken certain games.

For a more provocative example, consider the case of WeVibe, the vibrator made for long-distance couples and meant to be triggered remotely. Earlier this year, at the Def Con hacker conference, presenters demonstrated that the device was streaming data about its usage back to the manufacturer. The TOS for the device make this data collection legal, but it’s unlikely any of its users would approve of the company spying on their intimate moments. If buyers of the device owned the software, they could perhaps modify it to prevent this tracking, but, of course, they didn’t and the contract forbids tampering with it. (The company’s suggestion was to put the device in airplane mode—hardly a satisfying fix for a device that’s entire purpose is to be controlled remotely.)

These new contracts govern an ever larger slice of our lives—from how we read to how much privacy we get when we’re having sex. By proxy, the companies creating these products are deciding what we are and are not allowed to do. Nancy Kim, a law professor at California Western, refers to internet giants such as Google and Facebook as “quasi-governmental actors” for their ability to regulate every aspect of our lives, up to and including our freedom to speak. (Facebook is, after all, not a public space.) She describes terms of service contracts as a form of “private legislation,” which “reorder or delete rights otherwise available to consumers.”

Does anyone really care?

Despite tremendous erosion of property rights, most consumers transitioning to digital media have so far avoided the pain of losing anything they really cared about. Few have had a favorite ebook deleted or been embroiled in a legal argument over their digital inheritance.

The attitudes of young adults make ownership seem positively passé. Rates of homeownership are down, the “sharing economy” is up, and everything that can be streamed will be streamed. Perzanowski, an admitted pessimist, believes it is “…a real possibility that we are in the midst of a much deeper cultural shift away from ownership.”

However, it may also be that most people simply haven’t yet realized that they’ve given anything up. Such confusion is at least in part explainable by businesses continued use of words that imply ownership, such as “buy.” When Perzanowski and Hoofnagle’s tested a version of the Media Shop that replaced the “Buy now” button with a “License now” button study participants more accurately understood their rights. Additionally, about half of all shoppers were willing to pay more to acquire a digital copy that explicitly came with traditional ownership rights, such as the right to resell.

Scholars such as Perzanowski argue that the ideal solution is a restoration of property rights for digital goods. However, any legal fix would present significant technical, economic, and political challenges. A huge part of the global economy is now based on licensing intangible things. Unwinding that could take decades. The lobbying efforts against it would undoubtedly be overwhelming.

Courts could make a more immediate impact by simply refusing to enforce the worst parts of these contracts. The legal “doctrine of unconscionability” allows judges to throw out parts of a contract that are entirely one-sided. Unfortunately, courts have so far chosen to treat terms of service agreements the same way they treat traditional, negotiated contracts. Under that rubric, the bar to find something “unconscionable” is incredibly high, especially in cases where no money changed hands.

If consumers could be motivated to care, then the most plausible mechanism for reform may be a sort of 21st century consumer rights movement. In the last century public outcry led to regulatory reforms providing greater protection from manipulative financial terms, unsafe manufacturing processes, and other abuses. A modern equivalent could watchdog the worst abuses of software contracts and work to restore important legal protections, such as the right to modify the software in our devices so they can be repaired or repurposed.

Before anything like that can happen millions of users will have to, at a bare minimum, acknowledge that huge swaths of their lives are legally controlled by contracts they have never even read.