As the new school year starts in China, many colleges are welcoming not only students, but their parents too.

Universities across China are setting up tents and makeshift accommodations for parents staying overnight when they drop off their children at the start of the semester. Schools are debating whether the practice is undermining young people’s ability to be independent, but it has become increasingly common.

While the US’s “velcro parents” are known for having a hard time parting with their grown children as they head off to college, the situation in China is even more extreme. Most Chinese families only have one child, thanks to a government policy that dates back to 1979, and parents find saying goodbye to their only offspring especially tough. Making the situation even more fraught, many children entering universities in China are the first in their family to do so. So parents not only bring them to school and help them set up their dorm room, they bunk down overnight, or for several nights.

“We were very worried,” said 48-year-old Eve Zhang, who escorted Zhang Yan, her only child, to school. “So her father and I took ten days off and accompanied our daughter to Shanghai.” The family lives in Tianjin, 11 hours from Shanghai by car. Her daughter, she pointed out “has never lived in a dormitory” at any point in her 20 years. She and her husband spent two days helping Yan move in, and then toured around Shanghai for the rest of the time. “Not until we saw for ourselves that she was settled did we feel relieved,” Zhang added.

The practice of setting up so-called “tents of love” (link in Chinese) for parents to sleep in during this separation first started at Tianjin University four years ago. Other schools have followed suit since then, like Northwestern Polytechnic University and Guangdong’s Shantou University.

Shantou University set up 28 tents during the move-in period between Aug. 27 and Aug. 29 this year. Parents could stay in them free of charge.

“The two person ones are for couples,” said Lanner Lan from Shantou University’s student affairs division. Some parents even shared with complete strangers, “knowing that there were only limited numbers of tents,” she said. Hot water and shower facilities are provided in the gymnasium where these tents were placed.

“The tent is quite comfy with mats and air-conditioning, though without pillows,” said Huang Yiming, who slept in a tent at Shantou University with a stranger on Aug. 28th. “But for the kid, one night is fine.” His only child, Huang Zonghai, was admitted to the engineering school at the university.

“We couldn’t find an affordable and convenient hotel near the school because they were already fully booked, and there were dozens of other parents in a similar situation,” Huang explained. Making things worse, the seven hour bus ride from Guangzhou to Shantou on the move in day left him nauseous. He took two days off from the chemical factory where he works, without pay, to drop his son off.

Since then, “I call him every day to see how is everything going,” Huang said. “My son said he might be home during the National Day holiday in October.”

Tang, who only goes by one name, was pleased when his daughter was admitted into medical school at Shantou University last year. He escorted her on the 10 hour train ride from Guangxi Province to the university, after learning that the school provides free tents for parents of freshmen. “It’s a relief that I don’t have to find other accommodations, because I am a farmer,” he told (link in Chinese) Shantou University Youth, the university’s student press, last year.

Originally, Shantou University let parents stay in classrooms that contained chairs, tables and air-conditioners—but had no beds. They later upgraded to tents and mats “to make it more comfy,” said Lan.

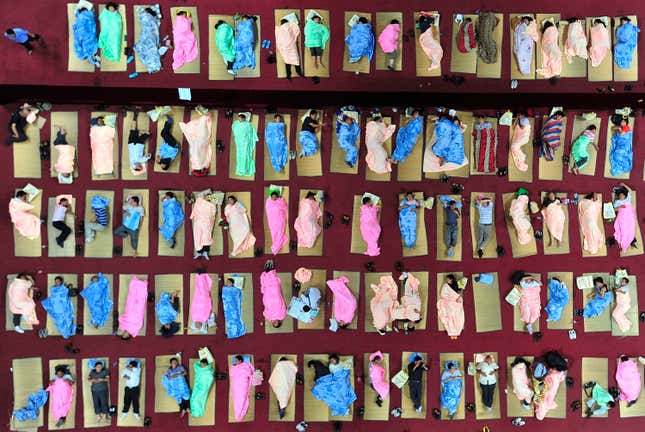

Other schools have set up giant sleeping rooms in gymnasiums and halls.

Many Chinese children say they appreciate their parents’ efforts.

Yvonne Wong, 22, the only child in her family, said her mother escorted her to South China Normal University in Guangzhou, where she enrolled as a freshman four years ago. Now, as she prepares to start a masters program in Hong Kong, she wishes her parents were by her side once again.

“There are too many things to carry and I need their help,” said Wong. Also, she added, “they might as well see how the university is. It’s something to be proud of.”

Often, incoming freshmen in China are accompanied by more than just their parents. Aunts, uncles, grandparents, and cousins come along as well. Last year, one student at Anhui University was accompanied by 14 family members. The school put the family picture on social media.

Software engineering major Liu Guoqiang has been helping freshmen register for classes for the past three years at Beijing Normal University’s branch in Zhuhai, a southern city. Kids joining the university are usually accompanied by anywhere from two to five family members, he said, with students coming from other provinces and cities more likely to have more family with them. “There was one time when the kid’s parents and grandparents from both parents’ side came—and they all helped cleaning the dormitory.”

After dropping their kids off, China’s one-child parents cope with their loneliness by staying in regular touch.

“I feel my heart is empty with my son gone,” said 50-year-old Hu, mother of Chen Tingtao, a student at Guangdong University of Foreign Studies in Guangzhou, capital of Guangdong Province. Chen’s parents, an uncle, an aunt, and a one-year-old baby all squeezed into a five-seat car with him to take him to school. Hu went to Chen’s dormitory three times to clean the room, help with unpacking, and get to know Chen’s roommates. “My son’s roommate is from Shenzhen (a southern city in Guangdong),” Hu said.

She has been texting Chen regularly over the past four days to ask whether he is eating well at school. But, she said, “we have to wait at least a semester” to see him.