Fifty years ago today, on Sept. 8, 1966, Star Trek premiered on television. It was an era of great uncertainty. Americans believed that nuclear war with the Soviet Union could happen at any moment. A wave of protests had spread throughout the country, highlighting the deep inequality faced by black people and women in the US. Leaders like John F. Kennedy and Malcolm X had already been assassinated, and more still would be killed before the decade was done. The Vietnam War was escalating, fueled by a fear that communism would spread throughout Asia. This was not a hopeful time to be alive.

But Gene Roddenberry, the creator of Star Trek, was a man who knew how to find hope in the midst of dark times. Before writing for television, he had served as the Pan Am co-pilot of a doomed airplane. With both engines failing, Roddenberry left the cockpit to walk the cabin and reassure passengers that they were “going to be okay.” After escaping the crashed plane, he ran back into its fire to rescue as many people as possible. He didn’t believe in no-win scenarios. This spirit of optimism made Star Trek unlike any science fiction series that had ever come before—it showed us a bold way forward.

Other sci-fi series either played into the paranoia of the times or sought to ignore it completely. The Twilight Zone offered cautionary tales about the many ways in which humans might destroy ourselves, and how the end times were just the beginning of our misery. Meanwhile, Lost In Space offered an escape with stories that were heavy on comedy but light on substance.

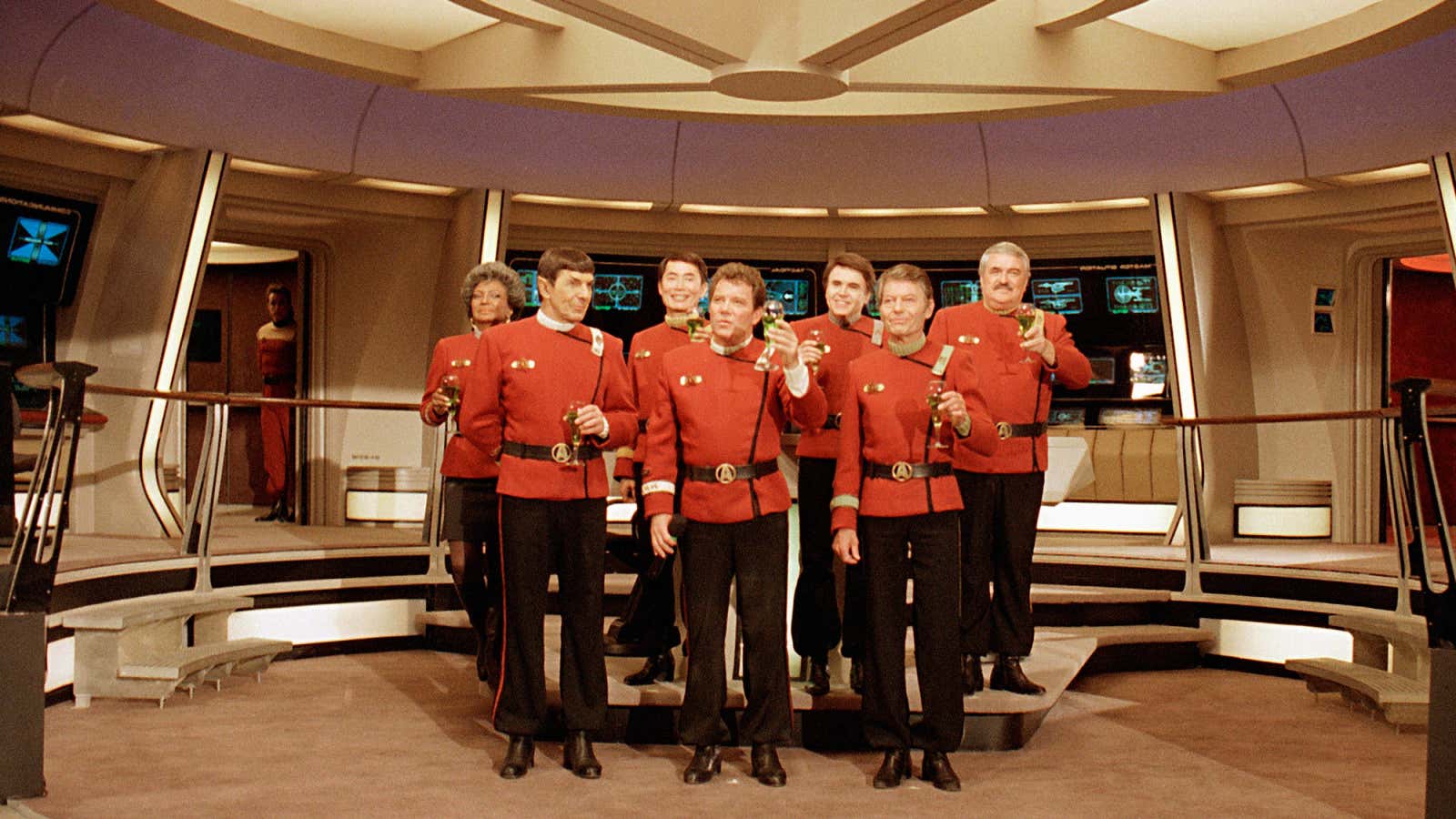

But Star Trek promised that the social unrest of the time could eventually lead to a better future. It envisioned an era where an American worked alongside a Russian, and a black woman was in a position of leadership. Humans had eliminated war and were united in a peaceful mission of exploration. These were radical ideas, especially when everything else on TV either reminded audiences that the world was tearing itself apart or sought to help them forget harsh realities.

While Star Trek was set in an utopian future, its stories were grounded in the real issues of the day. It wasn’t partisan, but it was deeply political. The Klingons and Romulans symbolized the Soviets and Chinese. This allowed Roddenberry and his team of writers, some of the best science-fiction authors of the time, to explore topics like the Cold War (“A Taste of Armageddon”) and discrimination (“The Devil in the Dark”). I wish I could add sexism to the list of issues on which Star Trek was ahead of its time. But beyond Uhura and Number One (from the rejected original pilot “The Cage”), most female Enterprise crew members tended to be reflections of 20th-century sexism rather than 23rd-century equality.

What was so brilliantly subversive about Star Trek was that it gave people a way to talk about social issues that they might otherwise avoid bringing up. We rarely speak up about politics when we believe that others don’t share our perspective. And when we do get pulled into politically heated discussions (think about your last awkward family dinner), the conversations mostly don’t go anywhere.

Psychology can help explain why this is. When we hear ideas that conflict with our beliefs, our minds fight that information in the same way our immune systems attack a virus. We’re wired to preserve the lens through which we view the world. This is why most conversations about politics don’t change our mind, but only strengthen our preexisting beliefs.

Star Trek, however, manages to bypass its audience’s political defenses because it presents real-world conflicts in ways that we find less threatening. Even today, bringing up the Vietnam War can be polarizing in conversation. But a story about the Federation and Klingons arming opposing tribes on the planet Neural (“A Private Little War”)? That sparks a real discussion, not a shouting match of partisan politics.

Sure, Star Trek doesn’t own the concept of political allegories. But it’s unique in its illustration of better ways to engage in political discussions.

Whenever Kirk was faced with a tough decision, for example, he brought his crew together to discuss the situation. His character never silenced dissent—one of the most dangerous things a leader can do. Instead, Kirk made it safe for everyone to share their perspectives, even those who disagreed with him.

When there was vigorous debate about a given issue, Kirk grounded the discussion in values everyone shared: the ethical treatment of sentient life, the protection of the crew, service to Starfleet, encouraging independence on alien planets, and the exploration of the unknown. Indeed, psychology shows that conversations that emphasize shared values can lead to real political persuasion. This isn’t easy to do. It means you have to listen to someone with whom you strongly disagree, understand what’s important to them, and find common ground. But if you’re willing to put in the effort, research shows it works.

Fifty years since Star Trek’s debut, the political landscape has changed. We live in a more polarized world. In the US, liberals and conservatives live in different regions, consume different media, dress in different styles, and eat different foods. As our politics and lifestyles have diverged, we’ve grown to dislike each other more, each believing that the other side is destroying America. We’re seeing similar trends in other democracies, with the United Kingdom voting for Bexit and a decline in centralist support throughout Europe.

The tragedy is that most of us care about the same things. We all want a strong economy, a safe and educated country, and healthy loved ones. But we can’t agree on how to move forward on these values. And it often seems there’s no hope that things will get better any time soon.

Perhaps this is why Star Trek has never lost its hold on the public imagination. It promises to help us cut through our polarization and the tribal psychology that keeps us apart. And so it’s fitting that a new iteration of the franchise, Star Trek: Discovery, is slated to premiere on CBS in January 2017. The series promises to take viewers back to the 23rd century, 10 years before the events of the original series, during a more unruly and less civil era. My hope is that the show will draw on its history of political allegory to start a dialogue about the biggest issues of the day—from global economic instability and climate change to mass shootings, systemic discrimination and terrorism. If Star Trek: Discovery can get us talking to one another, perhaps it can help us believe in a better future again.