A successful space mission could alter the destiny of Rustenburg, a dusty mining district in South Africa.

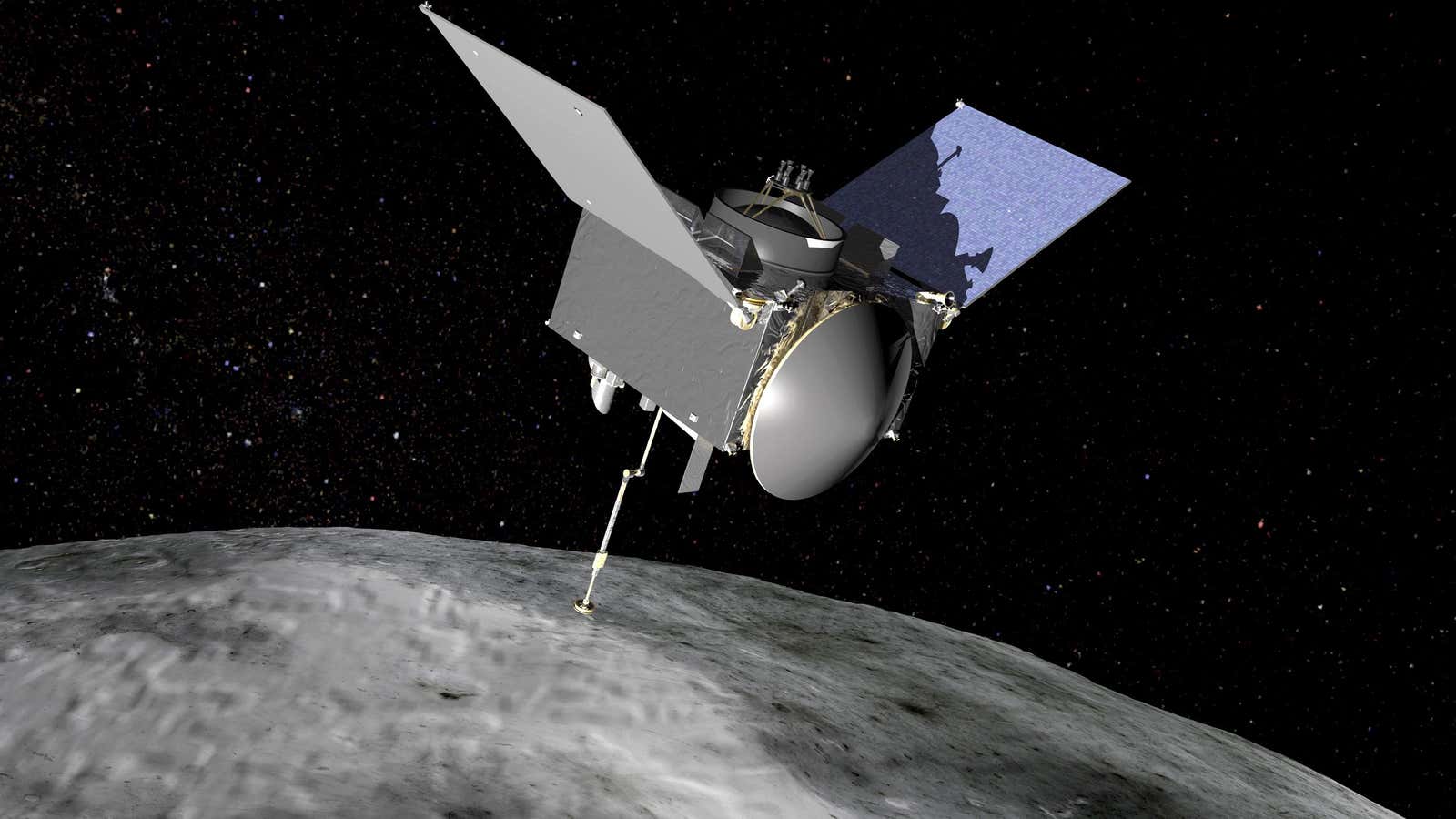

On Sept. 8, NASA launched the Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, Security-Regolith Explorer or OSIRIS-Rex. OSIRIS-Rex’s mission is to travel to the asteroid Bennu and return with a sample of “scientific treasure.” Among that treasure could be the potential to unlock thousands of tons of platinum, the main source of income for Rustenburg, and a significant revenue source for South Africa’s mining industry, the world’s number one platinum producer.

Thanks to studies of meteorites, we know that asteroids contain vast mineral wealth. OSIRIS-Rex is set to reach its destination in 2018 and will return a sample of between 60 grams to 2,000 grams (between 2 and 70 ounces) to earth. If the seven-year mission is a success, aspirant asteroid miners will be closer to dragging a platinum-rich asteroid closer to Earth, or mining it right there in zero-gravity. That could see Luxembourg could compete with South Africa, Russia and Zimbabwe, the world’s top platinum producers.

The small European nation announced earlier this year that it has partnered with asteroid mining company Deep Space Industries. By 2017, Deep Space Industries plans to launch it’s own small spacecraft on an experimental mission. Planetary Resources, another asteroid mining company that boasts the backing of Google co-founder Larry Page, has begun to test its probes in space.

A third mining company, Kepler Energy and Space Engineering, is keeping its strategy under wraps for now. Despite the exorbitant costs, asteroid prospectors are already popping up. In the meantime, NASA is also planning a robotic Asteroid Redirect Mission to drag asteroids closer to the earth, which could give companies and governments closer access, according to one forecaster.

Prospecting in space

But asteroid miners aren’t planning to compete with the earth market, says Charles Kieck, head of energy and precious metals at Afriforesight, a commodities research firm in Cape Town. Thanks to 3D printing, the aim is to use asteroid materials in space to produce equipment and spare parts for crafts going even further.

Space miners will first target water-rich asteroids for their hydrogen potential, then mineral-rich asteroids for their nickel and iron-ore. Platinum is a small by-product of their yield and has no use in space. But that means it poses a risk to the platinum resources below the earth’s surface, says Kieck.

“It’s not something that earth’s miners should have sleepless nights about at this stage,” he says, but it is important to start thinking about it. Mining is likely to start around 2030 on asteroids as small as 10 meters in diameters (nearly 33 feet) and could take 20 more years to target the larger, more lucrative asteroids. But just one of those could knock the Earth’s platinum industry off kilter.

An asteroid with a diameter of about 1000 meters (about 3280 feet) could yield about 100,000 tons of platinum, says Kieck. The earth produces a few hundred tons per year, on average. And even then, the main suppliers are struggling to keep up. South Africa produces more than two thirds of the world’s platinum, but the country’s mining sector has been racked by labor unrest and shaft closures. Even as mining experiences quarterly growth for the first time in recent years, Statistics South Africa says mining production has decreased by 5.4%, year-on-year in July 2016.

South Africa’s platinum industry is already crashing

South Africa’s 2016 output is expected to be down 6% from last year, according to the World Platinum Investment Council’s quarterly report (pdf) released on Sept. 8. The industry will take some time recover from the effects of high production costs, labor issues and shaft closures. Restarting halted supply, increasing existing production or even setting up new platinum production requires multiple years of investment, rather than the daily fluctuations of the dollar price or the weakening South African rand, the report said.

“Real cost increases due to labor costs—which account for over 50% of overall mining costs—continue and, together with low metal prices, they have driven the fall in capital investment across this industry. Sustaining current output is harder as a result,” said the council’s CEO Paul Wilson.

For the thousands of men forced to work underground and live above ground in impoverished conditions, being replaced by robots in space could have an advantage: the chance to break a generational human production line and pursue other ambitions. At worst, it could lead to more unemployment.

OSIRIS-Rex’s detachable capsule is set to only return to Earth in 2023, so South African mining magnates have some time. But South Africa has been reliant on mining as a main source of income since the 19th century, and even today, is struggling to diversify its economy. The NASA space mission doesn’t spell the death of the mining industry, but it is sending a signal that it’s time to evolve.