Roald Dahl is remembered for his solitary, kind-hearted child heroes—Charlie, who visited a chocolate factory, and Sophie, who befriended a floppy-eared giant, among them—and their triumphs over bullying adults. But the beloved British children’s book author was also known for the distinctive language he used to create the vivid, often dark, worlds in which the characters lived.

To honor the centenary of his birth this month, the Oxford English Dictionary has updated its latest edition today (Sept. 12) with six new words connected to Dahl’s writing, and revisions to four other phrases popularized by Dahl’s evocative stories. In May, the Oxford University Press also published a Roald Dahl Dictionary complete with 8,000 words coined or popularized by the author.

There was linguistic method to Dahl’s mad use of language. “He was using very linguistic principles,” says Vineeta Gupta, head of children’s dictionaries at Oxford University Press. Dahl invented words based on old words, rhymes, malapropisms, and spoonerisms (swapping the first letters of words around, such as “catasterous disastrophe” from The BFG). Dahl also played with sound (“sizzle-pan” to refer to a frying pan in The BFG, for example).

Here are the new Dahlisms added to the OED, and the revised phrases, with notes on their origins.

New entries

Dahlesque

The characteristics of Dahl’s work—in the OED’s words, “eccentric plots, villainous or loathsome adult characters, and gruesome or black humour”—now have their own adjective. The term was first used in 1983 by the literary magazine Books Ireland.

Golden ticket

These refer to the tickets hidden in chocolate bars that granted access to Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964). The first golden ticket, however, was awarded to 18th century painter William Hogarth, giving him admission to the Vauxhall Gardens in London, in recognition of his paintings of the venue.

Human bean

This is a mispronunciation of “human being,” uttered by the giant in The BFG (1982): “We is having an interesting babblement about the taste of the human bean. The human bean is not a vegetable.” The first instance of the phrase is over a century older, having been used in an issue of the British satirical magazine Punch in 1842.

Oompa Loompa

The diminutive factory workers who played music and danced in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory were made more famous by the 1971 film adaption of the book, starring Gene Wilder. Gupta called the phrase “typical Dahlesque,” reflecting how the author played with sound to convey meaning.

Scrumdiddlyumptious

“Extremely scrumptious; excellent, splendid; (esp. of food) delicious.” Although the word was first found in The American Thesaurus of Slang in 1942, Dahl’s giant’s use of it planted it firmly in the minds of every child who read The BFG: “Every human bean is diddly and different. Some is scrumdiddlyumptious and some is uckyslush.”

Witching hour

Referred to in The BFG as ”a special moment in the middle of the night when every child and every grown-up was in a deep deep sleep, and all the dark things came out from hiding and had the world to themselves.” We can thank Shakespeare for this evocative phrase: according to the OED, “witching time” first appeared in Hamlet (1604).

Revised phrases

Frightsome

Another word from The BFG, meaning to cause fright. It was first used by the Scottish poet and army officer William Cleland in 1689, in which he refers to “walled cities [and] frightsome forts.”

Gremlin

The OED updated its definition of this term to reflect that Dahl’s 1943 novel, The Gremlins, helped popularize it. The phrase itself originates in Royal Air Force (RAF) slang from 1929, referring to a menial or lowly person. By 1942 it was being used by the RAF to describe mechanical glitches—Dahl’s novel itself centers around mythical creatures who sabotaged aircraft, the inspiration of which is said to have come from Dahl’s time as a fighter pilot during World War Two. Writing in a 1944 edition of its journal American Speech, the American Dialect Society explained that “the gremlin seems to be extending its sphere of operations, so that the term can be applied to almost anything that inexplicably goes wrong in human affairs.”

Scrumptious

The OED dates this word, originally an English dialect term for “stingy,” back to 1823. In Dahl’s James and the Giant Peach, published in 1961, the Centipede says: “I’ve eaten many strange and scrumptious dishes in my time.” Its shorter variant, “scrummy,” was first used in 1844.

Splendiferous

Remarkably fine; magnificent, splendid, according to the OED. In Dahl’s Danny, the Champion of the World (1975), Danny’s father refers to his own dad as a “magnificent and splendiferous poacher.” The state of being splendiferous is an equally superb word: splendiferousness.

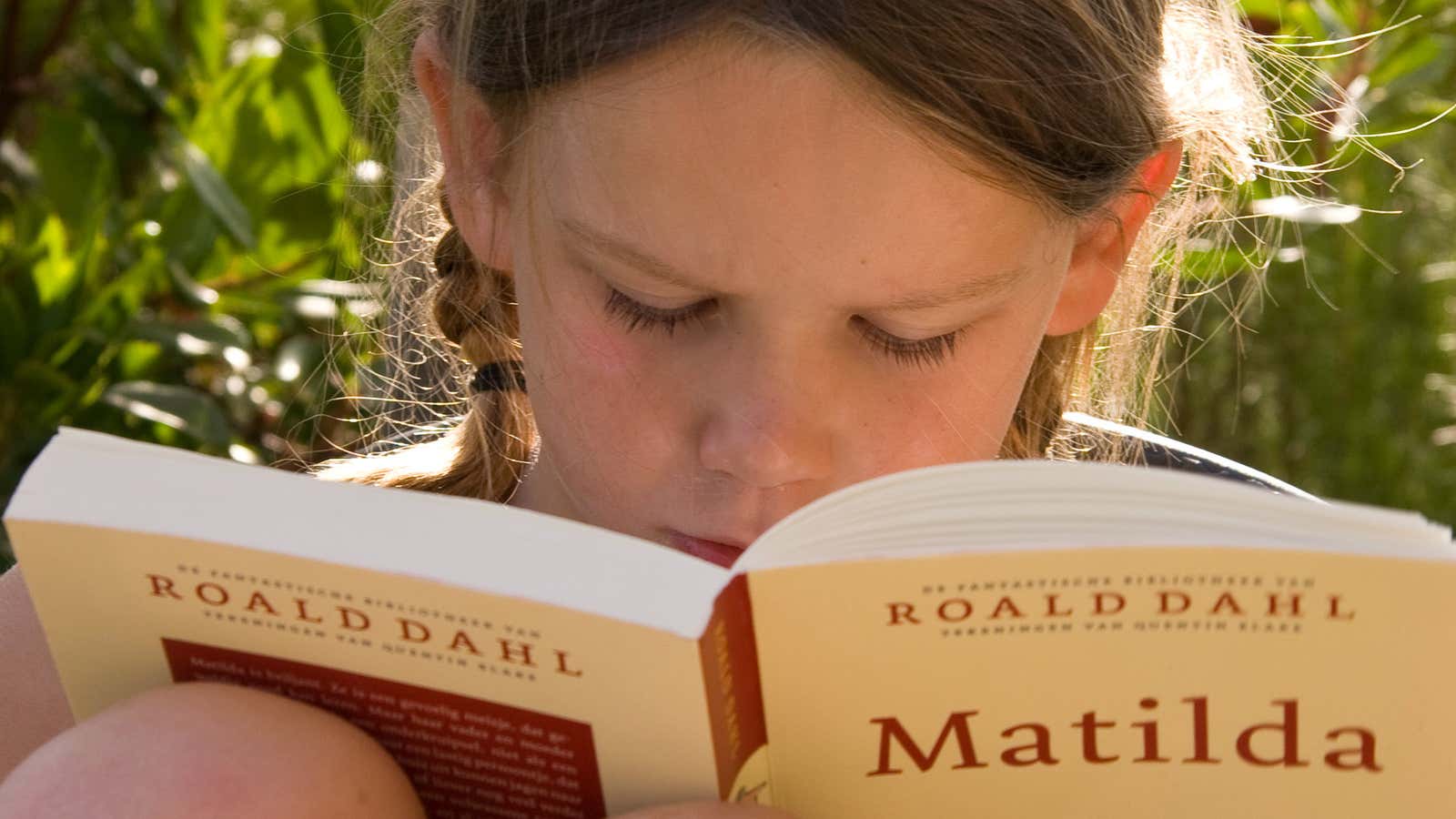

Image taken by Jan Willem van Wessel on Flickr. Used under a Creative Commons license (CC BY 2.0)