Life as a Chinese government official isn’t what it used to be. Lavish, liquor-heavy banquets have been outlawed. It will soon be harder to get those handy military license plates, useful for avoiding hassle from traffic police. And these days, with China’s army of voracious and ever-watchful bloggers, every inappropriate smile, public temper tantrum, or luxury watch collection soon gets seen by the entire country.

The plight of the Chinese official isn’t an issue many rally behind. The thousands of men and women who help run the country in posts ranging from head of an industrial park to a minister, are vilified by the public for their wealth, elite connections, and privileged treatment. Officials are more often than not seen as part of China’s problems with government corruption and negligence.

And yet, it’s not easy being red and feeding from the iron rice bowl. Chinese officials, like political dissidents or regular citizens, also suffer under a party that is accountable chiefly to itself and a government that arbitrarily enforces laws.

In the last two weeks, two Chinese officials have mysteriously died after being detained by authorities under the party’s internal discipline system, shuanggui. The family of Jia Jiuxiang, vice president of a court in Henan province, said Jia turned up badly bruised at a local hospital after being detained for 11 days. He died on the morning of April 25.

A week ago, a Chinese official by the name of Yu Qiyi died after arriving in a local hospital in Zhejiang province beaten, with blood coming out of his nose and ears. Chinese state media said Yu had “suffered an accident” while being questioned by party discipline officials. In both cases, reports said the officials were being investigated for corruption, but no more details were given.

Jia and Yu are just two examples of many more officials subject to shuanggui, which translates roughly as “double regulation,“ a way of keeping cadres in check that is essentially a separate, opaque, judicial system just for party and government officials. This table from Dui Hua Human Rights Journal summarizes some other well-known cases:

What little is known about the process comes from select stories reported in Chinese media. An official is detained, usually without notice. In the case of Jia, he was picked up by authorities on his way home from a trip and managed to make one hurried phone call to his ex-wife, the last time they spoke before his death. Other officials’ deaths have been attributed to vague and strange causes like drinking boiled water or playing hide and seek.

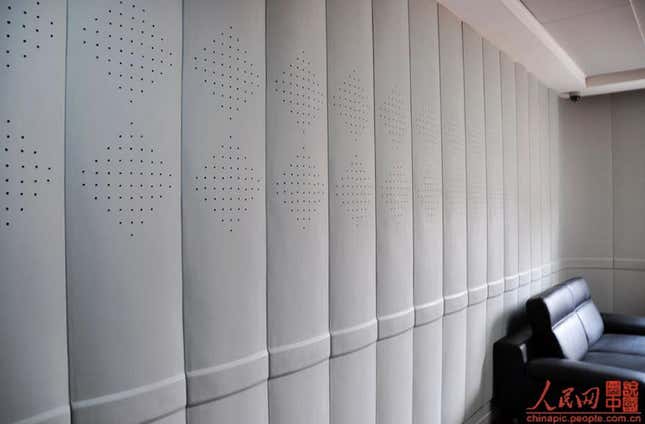

“The idea that the party essentially runs its own separate justice system, detached from the formal justice system, is a real concern,” Sophie Richardson, China director for Human Rights Watch, tells Quartz. Detainment can last for days or months—in some cases, officials have disappeared for years. Isolation, torture, and sleep deprivation are common interrogation techniques, experts say.

Officials in question usually lose their posts, careers never to be rehabilitated, and see all their property seized. High-profile cases are sometimes made into criminal cases to go through the regular justice system, but the verdict has already been determined. Suicide is common before that point.

Now, more officials may be at risk under an anti-corruption campaign launched by China’s new leader Xi Jinping. The party appointed one of its most well-respected officials, Wang Qishan, as head of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), which implements the shuanggui—a sign some have taken to mean a serious crackdown is underway. Authorities say they have investigated over 660,000 officials over the past five years.

Officials at levels higher than Yu and Jia, who can often be protected by other elites, don’t appear to be immune and in some ways they are more vulnerable. Former railway minister, in charge when a high speed train crash killed dozens in 2011, was charged for corruption and abuse of power earlier in April. Bo Xilai, fallen former powerful party secretary of Chongqing, hasn’t been seen in public since last year and has still not been tried in court.

Yet, the fact that the recent deaths of Yu and Jia were reported in national Chinese media may be a sign of a rising tide of opposition. ”It means that criticism is getting greater. They were under no obligation to report these deaths. This was a choice that someone made. The easiest thing to do would have been to cover up the whole thing,” Flora Sapio, an expert in Chinese law at Chinese University Hong Kong, tells Quartz.

Defenders of shuanggui, which dates back to the early days of the People’s Republic, say it’s akin to an internal audit of a company. Over the past decade, leaders have spoken more openly about the system and made efforts to institutionalize it with guidelines. In 2009, the head of the CCDI said in a press conference that shuanggui operates under stringent regulations that ban corporal punishment and mandate respect for “the dignity” of those investigated.

Still, shuanggui is shrouded in mystery. There are no available data for how many officials are disciplined through it or to what extent regulations are followed, according to Sapio. ”Officially, it can be used only on officials who serve at the county level and above, and only in what [the party] calls ‘important and complicated’ cases of corruption or official crime. The problem is, what is ‘important and complicated’?” she says.

The system is likely to stay as it is. Officials in opposition would have to prove an alternative discipline system is better or that shuanggui is not effective, Sapio says. Moreover, it is a way to discipline officials out of the public eye and keep scandal to a minimum. Drawing media attention to the recent grisly deaths may have simply been a call for the rights of officials to be respected, not to disband shuanggui. Given how many Chinese, ready pounce on chances to expose corrupt officials, see rough treatment of corrupt officials as rightful retribution, it’s hard to see China changing course soon.