Digital paintbrushes in Microsoft Paint or Adobe Photoshop work a lot like they do in real life: you pick a color and drag the brush along the canvas to apply paint. New research from Adobe and the University of California, Berkeley envisions the paintbrush as much more: a collaborative tool between human and machine.

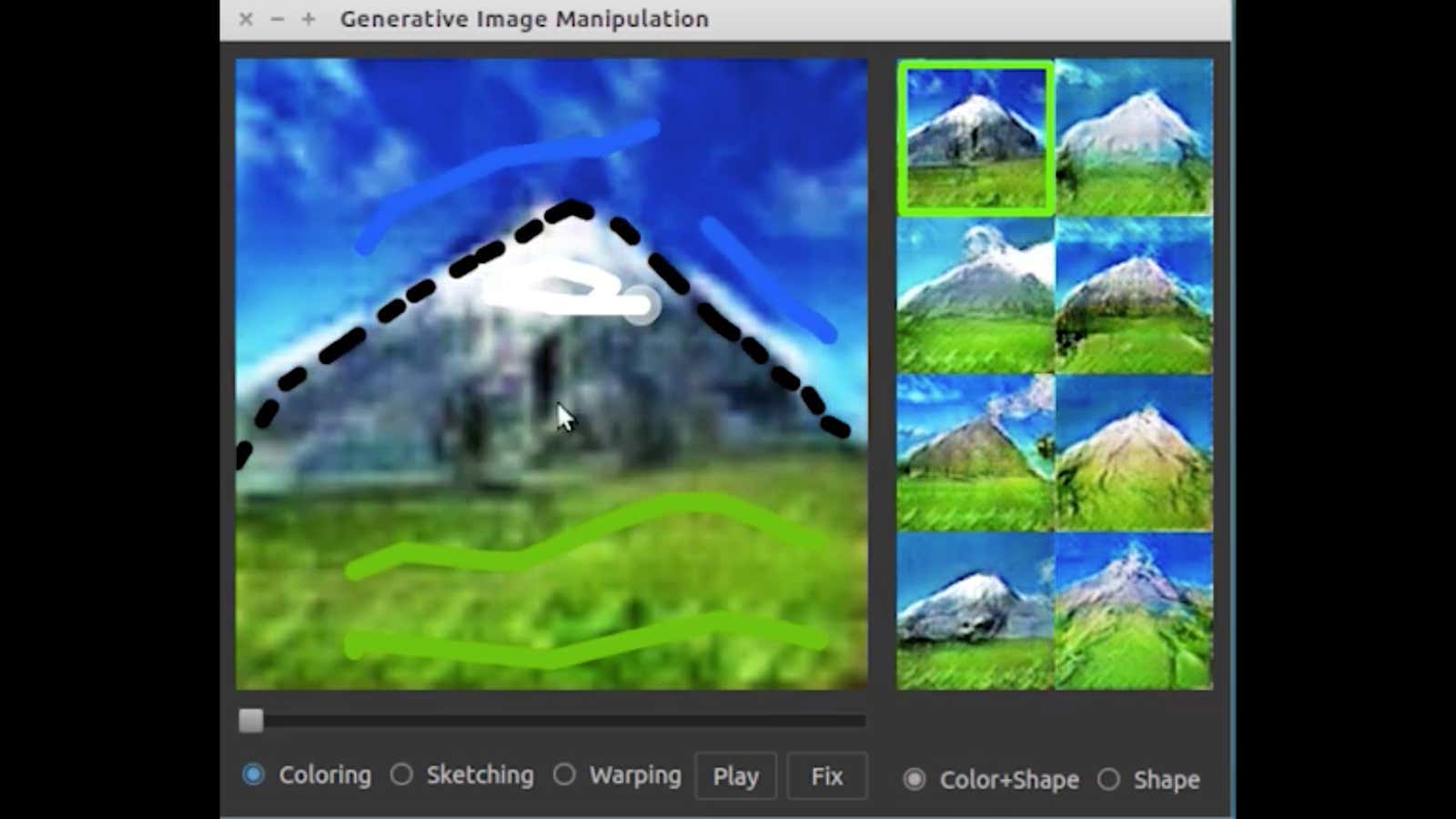

The software uses deep neural networks to learn the features of landscapes and architecture, like the appearance of grass or blue skies. As a human user moves the digital brush, the software automatically generates images inspired by the color and shape of the strokes. For example, when researchers testing the project made a blue brushstroke, the software painted a sky. It’s an example of the work being done in a field of AI research called “generative art,” discussed in a recent paper accepted by the 2016 European Conference on Computer Vision.

The same deep neural network used by the Berkeley-led team is also able to generate new kinds of shoes and handbags, using a reference image as a template. In one example, researchers were able to change the design of a shoe by drawing a different style and color on top of it.

Maybe that doesn’t sound impressive, but getting an AI to generate scenes and objects is a good barometer for how it understands our physical world. For an AI to create a new style of shoe, the algorithm needs to ingest thousands of examples of shoes. But even that’s not enough to get it to actually come up with something that is both new and makes logical sense.

AI systems work by finding similarities and patterns within the information they’re given, and through those commonalities in the data they form their concept of each item. When asked to generate a new idea, it’s usually easy to see how they came to it. For instance, in 2015 when Google researchers asked their AI to produce new images of dumbbells, most dumbbells had disembodied arms attached, because the two were so highly correlated.

The Adobe and UC Berkeley research is an advanced extension of that sort of work, tuned to understand the nuance of form and color. Drawing a dark-colored, upside-down V triggers the AI to conjure a mountain or church steeple, where it’s seen the shape and color before. A blue line above that becomes a fully-realized sky with various hues of blue, and a green line below becomes textured grass. These examples aren’t random, and the AI can’t paint things it hasn’t already seen. To make the landscape-generating tool, the team had the algorithm process more than 275,000 images of churches and landscapes. The software decides the fine details, making the process more collaborative than traditional art. If this were an orchestra, the human would be the conductor of machines rather than the composer of the piece.

This isn’t the first time Adobe has tried to develop AI that can solve creative problems. DeepFont, their AI font detection software, can reportedly recognize 20,000 fonts in images and online. There’s no guarantee that this will end up in an Adobe product, but it seems the company has some ideas about how humans and machines might collaborate in the future.