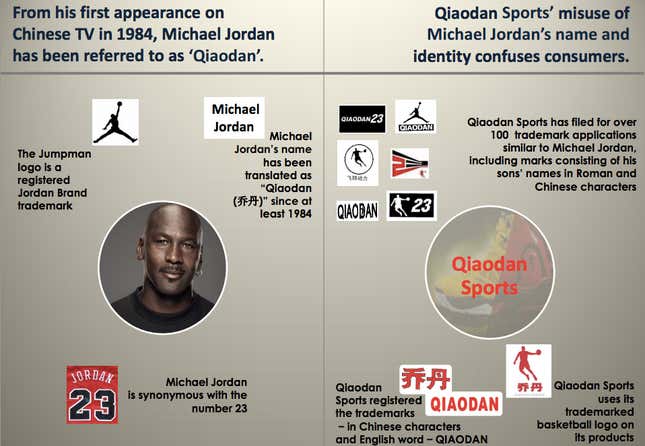

The real Michael Jordan is standing up—against Qiaodan, his Chinese imitator, in a Shanghai court. Today was the first day of trial in the lawsuit brought by Michael Jordan—you know, “Air Jordan”—against Qiaodan Sports Co. (乔丹, an ostensible Mandarin transliteration of “Jordan,” pronounced “chee-ow dahn.”) The suit will test the Chinese legal system’s recognition of personal trademarks, something increasingly important to the country as it seeks to upgrade its protection of intellectual property.

Qiaodan Sports sells basketball shoes and jerseys emblazoned with #23 (Jordan’s number as a player) in more than 5,700 outlets throughout China. The 49-year-old former Chicago Bulls star wants the defendants to stop using his name, and has asked for $183,000 in compensation, say Jordan’s lawyers. Jordan plans to donate the money if he wins to “growing the sport of basketball in China.”

Jordan’s suit against Qiaodan alleges that it has misled its customers in thinking that he authorized its use. The suit was filed just as Qiaodan Sports, which brought in 1.7 billion yuan ($276 million) in revenue last year (pawyall), began planning a public listing in Shanghai.

Here are some highlights of Qiaodan Sports’ legal approach to the challenge from Jordan:

- Qiaodan Sports lawyers says that the “original intention” for picking the disputed name was to evoke “grass and trees of the south” (link in Chinese). This despite its having registered “杰弗里乔丹,” “Jiefuli Qiaodan,” “马库斯 乔丹,” “Makusi Qiaodan.” Michael Jordan’s sons are named Jeffrey and Marcus.

- Qiaodan says 4,600 Chinese citizens are named “Qiaodan,” and that the rights to the name therefore doesn’t belong exclusively to Michael Jordan (link in Chinese).

- “Qiaodan” isn’t Michael Jordan’s actual surname (link in Chinese).

- Michael Jordan doesn’t live in China, and therefore has no right to bring the case.

- In early April, it countersued Michael Jordan for misleading the public and preventing the company from pursuing an IPO (link in Chinese). Qiaodan Sports wants $8 million in compensation.

And here’s how Jordan’s camp sees it (courtesy of the Jordan lawsuit’s website):

Jordan might have a chance here. Two previous suits from basketball stars—Yao Ming’s and Yi Jianlian’s—have proven victorious (rundown from intellectual property lawyer Stan Abrams here).

Mind you, Qiaodan Sports registered the “Qiaodan” trademark in 2000; Nike, which owned the rights to the “Jumpman” logo that Qiaodan Sports’ so closely resembles, had registered only the English version of “Jordan,” in 1993. Nike’s legal efforts against Qiaodan have all failed, as authorities have ruled that “Qiaodan” doesn’t uniquely imply Michael Jordan.

As for the countersuit, the two Jordan/Qiaodan legal showdowns are independent. Qiaodan Sports was apparently frustrated that negotiations hadn’t panned out, and that the suit was holding up its IPO plans. The company had been ramping up production in anticipation of going public, and among other things, has invested heavily in a new R&D center. One wonders what it might be researching and developing. Various ways to write Shabazz Muhammad, Ben McLemore and Kelly Olynyk in Chinese?