In May, a Florida man named Joshua Brown engaged the autopilot function on his Tesla S, and relaxed to watch a Harry Potter film. A little while later, the car smashed into an 18-wheel semi-truck. Brown was killed.

Since then, Tesla’s autopilot self-driving system has been subject to intense scrutiny. One question raised is whether Tesla CEO Elon Musk recklessly named, released, and promoted the system in a way that lulled his customers into wrongly believing that they could drive hands-free. The accident has challenged Tesla’s credibility, and by extension that of all self-driving systems.

Product safety is an ultra-sensitive issue, particularly when it comes to systems whose malfunction can lead to death. The history of our two centuries of industrialization may seem callous. Yet we also know, but sometimes forget, that our transportation revolution—going from the horse at the beginning of the 19th century to the possibility of a human voyage to Mars in a decade or two—has involved many fatalities.

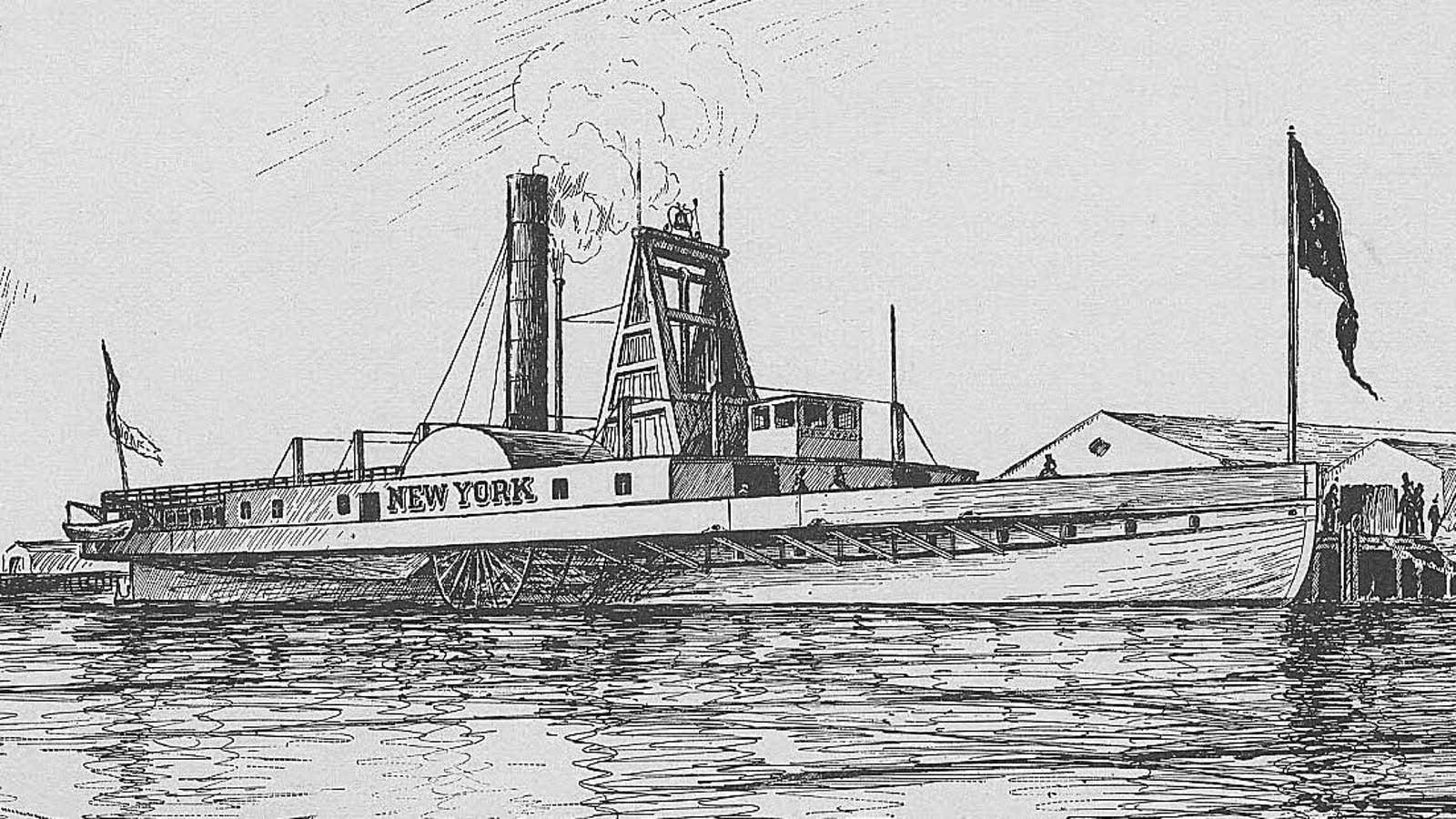

Take the first big advance in industrial transportation—the steam engine. In a single accident in 1838, 80 people died when the boiler aboard the steam ship Moselle blew up on the Ohio River. From 1816 to 1848, it was one of dozens of explosions and other accidents involving US river steamboats that killed 1,433 people, according to Bloomberg.

The 19th-century titan Cornelius Vanderbilt got his start as the captain of a ferry taking passengers between Staten Island and Manhattan. On June 7, 1831, his younger brother Jacob was piloting the General Jackson, a ship they owned together, along the Hudson River, when the engine blew. Here is what happened next, according to The First Tycoon, the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of the magnate by T.J. Stiles:

Shattered pieces of wood, metal fragments, and shreds of clothing showered the water and the dock as some 40 passengers screamed in panic or pain. At least nine would die from the scalding shock wave of steam, and two more were sealed in the sunken hull.

People have been dying in automobiles, too, almost since they were invented. The first known fatality was Mary Ward, an Englishwoman who in 1869 was riding in a car when she was thrown onto the road. According to her obituary, “The vehicle had steam up, and was going at an easy pace, when on turning the sharp corner at the church, unfortunately the Hon. Mrs. Ward was thrown from the seat and fearfully injured, causing her almost immediate death.” Today, 1.3 million people die every year on the road around the world.

Every individual death is a tragedy, and to chalk up fatalities as a cost of progress is to be banal and trivial. Yet, 19th century passengers continued to use the ferries and automobiles, leading to railroads, highways, and shipping that today reflect the networked globe. Further deaths may happen in self-driving vehicles—a lawsuit in China blames Autopilot for the death of a 23-year-old man there in January. But experts say the Tesla cars, or their successors, will ultimately save lives since driver error is a role in most accidents.