When the UN’s flagship cities conference Habitat III meets in Ecuador on Oct. 17, the assembled mandarins and policy experts are set to make several calls to “prevent and contain urban sprawl.” On the surface, this should cheer the many urbanists who have long bemoaned sprawl’s damage to the environment, communities, and citizens’ wellbeing.

Urban sprawl costs the US economy over $1 trillion per year (5.4% of GDP) through time, land, and energy waste, according to the London School of Economics. It forces the poorest in Mexico City to spend six hours a day on interminable bus journeys, killing hope for social mobility. And the environmental harm piles up, with bigger houses that cost more to heat and force long car rides to groceries and any fun.

But there are two big problems with a policy of “preventing” sprawl. Firstly, the term “sprawl” is so vague that many academics shy away from using it at all–and admonish the UN for making its suggestions in such vague language.

“It’s a very messy concept and it’s a terrible diagnostic tool,” says Robert Bruegmann, professor emeritus of urban planning at the University of Illinois at Chicago and author of Sprawl: A Compact History. “Just to say ‘to prevent sprawl,’ you have no idea what it’s talking about. Is that about density? Is that about form? It really isn’t clear what they mean by trying to stop sprawl.”

If we broadly define sprawl as ‘cities expanding across the horizon in low-build houses,’ the next, somewhat bigger, issue is that in reality it probably can’t be stopped–especially in the rapidly-urbanizing Global South, according to New York University city planning professor Shlomo Angel. Instead of fighting it, he argues we should focus on how to deal with sprawl in a manageable, environmentally-friendly way that doesn’t cut off the urban poor.

“[Cities] can’t contain expansion. Expansion is growing in leaps and bounds,” says Angel, who heads an NYU initiative that advises cities on how to make sprawl as “vibrant, inclusive, and affordable” as possible. This rules out, for example, simply drawing an urban boundary to limit sprawl; places like Seoul and Portland, Oregon, have tried that and house prices have gone through the roof, making the cities unaffordable for many.

The good news is that new technologies should help make sprawl much less costly than in the past. In the relatively near future, we’ll have driverless electric cars, which will dramatically lower the environmental costs of voyaging out to low-slung areas, Angel points out. With solar energy becoming ever cheaper, he adds, it could actually be easier and more valuable to put solar cells on small houses dotted across the landscape than on giant tower blocks packed in a small space. However, a plan like that needs to be balanced against the costs to community of living in spread-out areas—and, crucially, needs to account for the precious little time we have before global temperature levels reach a point of no return.

“The solution is to organize the urban periphery better than [planners] have done to this day,” Angel says. “They’ve taken the easy way out, all the people that want to stop sprawl. It’s kind of an anti-planning movement–saying ‘we don’t want expansion, we’re not going to plan for it.’” But that doesn’t stop the city from expanding, Angel says, and because it’s unplanned, the expansion will be disastrous.

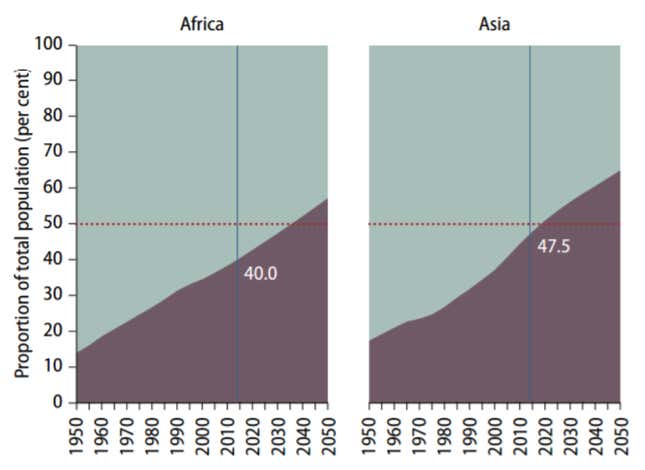

Cities vary enormously across the world. The West is over 75% urbanized, with Europeans living in more compact, public transport-focused cities with a clear urban center, while North American urban areas tend to extend over vast distances in endless suburbs and rely on cars. In Latin America, the population is around 80% urban; in cities there, the rich stay in the center while the poor spread out in ramshackle housing on the edges. Meanwhile, Africa and Asia are still mostly rural, with only 40% and 48% living in their respective cities. That means they host around 90% of the world’s rural population—but people are leaving the countryside in droves. The UN expects Africa’s urban population to triple by 2050 and Asia’s to rise by 61% in that time.

And, even within any single country cities differ dramatically in countless ways. So, clearly, a one-size-fits-all approach to managing sprawl won’t work. To bring some rigor to the issue, urban designer and anti-sprawl campaigner Peter Calthorpe has diagnosed three types of urban sprawl typically seen throughout the world: high-income sprawl, low-income sprawl, and high-density sprawl.

High-income sprawl

Picture an unending sea of North American suburbs. This is the epitome of high-income sprawl, resulting from a period in the 1950s and 60s when “white flight” saw wealthy families flee the cities for the perfect lawns and shiny cars that became symbols of the post-war American dream.

Suburban growth was perfect for industrial America, whose economy was powered by mass-spending on consumer goods needed to fill these vast houses. However, today’s innovation-driven economy requires people living closer together to regularly discuss and bounce ideas off each other, says University of Toronto professor Richard Florida, once branded the world’s most influential thinker by MIT.

“We live in a knowledge economy–what does a knowledge economy require? Density. What does every economist tell you? Clustering is the main driver of economic growth,” said Florida, speaking at NYU’s Shack Institute for Real Estate on Oct. 13.

The current heavily suburbanized situation is woefully inefficient, but there are definitely promising signs around, says Philipp Rode, executive director of the London School of Economics cities institute.

Many urbanists say high-income sprawl reached its peak during the 2008 financial crisis; in 2011, for the first time in almost a century, America’s cities began growing faster than its suburbs. The trend has held in the five years since, though suburbs have gained back a bit of ground.

Younger people in particular increasingly want apartments in “revived inner city areas with high density, where they can walk, cycle, take public transport…even in [heavily sprawling] Atlanta you have these small inner city developments that are being rebuilt,” Rode says.

Meanwhile, Los Angeles, the ultimate automobile city, has a $40 billion public transport investment project underway. Investments like this and policies like charging road tolls or a pollution tax—which might, for example, tax commuters not just for the cost of roads that service suburbia but also for the amount of carbon their driving produces—should help these cities become slowly denser over the coming decades.

Don’t expect things to change too fast though: “We’re just at the early stages–these are double generational events,” Florida said.

The real battleground, however, is in the Global South.

Low-income sprawl

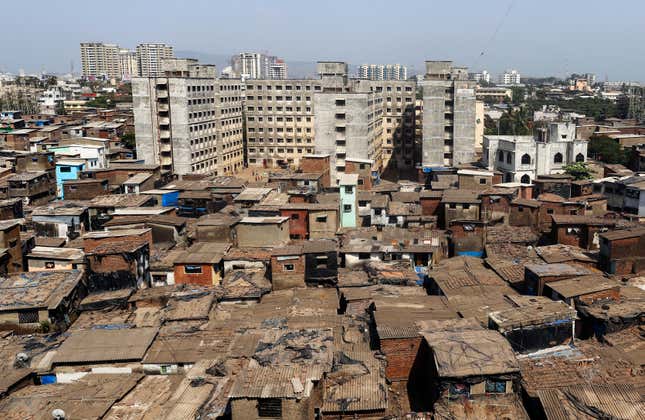

Throughout Latin America, Africa, and parts of Asia such as India, the poorest urbanites tend to be pushed to the periphery, and live in ad hoc housing with dire public transport and enormous commutes. Figuring out this low-income urban sprawl is crucial because these cities will grow by around two billion people by 2050, meaning, unlike in the West, much of their infrastructure is yet to be built.

The most obvious way to create density is by building up rather than out. But this is often out of financial reach in developing countries, Angel says; both the construction and upkeep of taller buildings are far more expensive than low-rise. Given this lack of funds for good quality high density buildings, Bruegmann says letting people sprawl is the only ethical option in some cities.

“To rein in development instead of encouraging it in these extremely high density places—it’s inhuman,” says Bruegmann. “If you have a place like Lagos or Dakar where you’ve got people piled up with 100,000 people per square mile, that’s lethal because they don’t have a sewer system, and they don’t have fresh water delivery. Those people would be much, much better off if they could disperse more into the surrounding landscape.”

For governments with so little disposable cash that building public housing isn’t an option, there can be little choice but to let ad hoc developments spring up—but this doesn’t mean they can’t be ordered with an eye to the future. One answer is to follow these settlements with infrastructure wherever they are built, providing them with sewage and safe drinking water. Where there aren’t funds to do even that, governments should preserve untouched corridors of land to be developed with infrastructure when there are funds later on, Bruegmann says.

“If you’ve just developed over everything, trying to put in a sewer is going to be exorbitantly expensive, whereas if you leave a corridor, that gives you at least something to work with when you’re trying to retrofit,” he says.

But for Ananya Roy, professor of urban planning at the University of California, Los Angeles, there is little excuse for the lack of public housing in India and parts of Africa. It is unjustifiable, she says, that governments pay to illegally convert agricultural land into big, sprawling houses for the rich, or massively subsidize projects for enormous multinational companies to set up shop in these cities, when the locals themselves live in absolute poverty.

“The urbanization of the wealthy not only remains undertaxed but often creates a strain on the urban and natural environment, and those externalities are rarely priced and rarely do we ask anyone to pay for them,” she says.

Instead, funds and political capital should be spent on giving “security of tenure” to people in slums, which would guarantee they can’t be evicted or have their homes demolished, Roy says. This security encourages people to invest to improve their housing, while the government should also provide infrastructure where possible. Projects like these have shown signs of working in India and Brazil but both lost political momentum due to changes of government or policy focus, she says.

Beyond housing, most jobs are still found in city centers, meaning people in these spread-out settlements need a speedy way to get to work—but massive roads chock-full of private cars is not the solution, says Calthorpe, who wrote about the issue in his book Urbanism in the Age of Climate Change. Instead, new boulevards should be dedicated to rapid bus routes, which are more sustainable and make for quicker commutes (while also costing much less than building new light rail systems). When self-driving electric cars become affordable, governments could invest in smart public car networks and phase out buses.

Small, unsexy planning tweaks can also make all the difference, says Rode. For example, leaving less space between plots and building two or three stories instead of bungalows can double or even triple density rates in places like Africa and India. “We’re not talking about high-rise buildings,” Rode says. But we can’t “develop urban land like a little rural village, where you have big space around your individual buildings and then you really go completely into the horizon.”

High-density sprawl

Seemingly a contradiction in terms, “high-density sprawl” is found mostly in China, where cities expand out in huge, dispersed tower blocks, separated by giant, traffic-jammed roads. But instead of building them in coherent mixed-use clusters, jobs and amenities are nowhere near the housing blocks, and residents to travel long distances between them, says Calthorpe.

“They’ve taken the old modernist super block, ‘towers in the park,’ to an absurd degree,” he says. “They’re sprawling at high density—the densities that they’re building…there’s no human scale, there’s no walkability.”

But experts are confident China is learning from these mistakes. As Randall Crane, an urban planning professor at UCLA, puts it, “they wanna do the right thing.” China’s cities have grown by over 200 million people since 2004 and will absorb almost 300 million more by 2050, so sprawl and some mistakes are inevitable, but Beijing has been working with the World Bank to develop expertise on how to make cities more inclusive. China is ramping up public transport projects, and building new mixed-use areas (and revamping old developments) so residents can easily move between the office, shops, and home.

“These cities, yes, they are sprawling too much but they will ultimately not follow the super-dispersed American style of suburban sprawl,” says Rode. “Even suburban Chinese cities today are much denser than what we have seen in the US,”

At the moment, however, many countries in the Global South seriously lack the design expertise to negotiate these complex decisions on a large scale and with considerable time pressure. Nigeria and India’s cities will grow by about 600 million people combined by 2050, but the two countries only have 1.44 and 0.23 urban planners per 100,000 people, respectively—compared to 38 per 100,000 in the United Kingdom.

So, instead of focusing efforts specifically on preventing urban sprawl, the UN’s New Urban Agenda to be announced in Quito could instead lend real help in offering policy ideas of how to manage and plan for it—especially with an eye to tackling the global problem of urban inequality, which is often reinforced through poor or corrupt planning.

“To say, ‘Sprawl’s bad, we should stop it,’ that just leaves a lot of details on the table,” says Crane.” It’s like saying, ‘We have a conflict with Syria, we should address that.'”