For some of us, our DNA is a time bomb. Small inherited genetic mutations heighten our risk for diseases from cystic fibrosis to breast cancer that explode in our adult years, usually without warning. That’s because only a fraction of those at risk will ever have their DNA tested. Most genetic diseases are rare, and the tests are too expensive to administer to everyone.

Take breast cancer. Of the 248,000 cases of breast cancer each year in the US, about 5 to 10% are caused by mutations in the BRCA gene (the same variation that led Angelina Jolie to have a double mastectomy in 2013.) Yet screening every women in the US for this mutation, one study found, would cost $400 billion, more than ten times the entire research budget of the National Institutes of Health. In 2015, a JAMA Oncology study found the price per test would have to fall 90%—to about $250—to be cost effective at a national level.

That day is here: the startup Color Genomics just announced a “family” breast cancer testing program, where certain qualified women can get tested for just $50. Essentially, if you have a close relative who has already been diagnosed with a hereditary cancer mutation, you can get a $50 BRCA test—without going through insurance or even a doctor’s office. Perhaps more importantly, anyone can order Color’s broad genetic-screening test, that includes BRCA, for $249. Anyone who wants a genetic screening can call up Color Genomics to have an independent physician review and order the test, as well as genetic counselors help interpret the results. (Counsyl, another DNA screening company, offers similar services that bundle the test with broader testing and genetic counseling, at prices from $350 to $900, although the company works primarily through insurance companies and outside physicians.)

Color was founded by Elad Gil and Othman Laraki, a pair of early Twitter employees, along with engineers from Google, and their mission is to make BRCA testing routine. If it happens, it’ll be be because DNA sequencing is getting absurdly cheap and startups like Color are now building diagnostic labs from scratch rather than ordering off-the-shelf software and conventional equipment—which is expensive and requires a ton of manual labor a time to execute a single test.

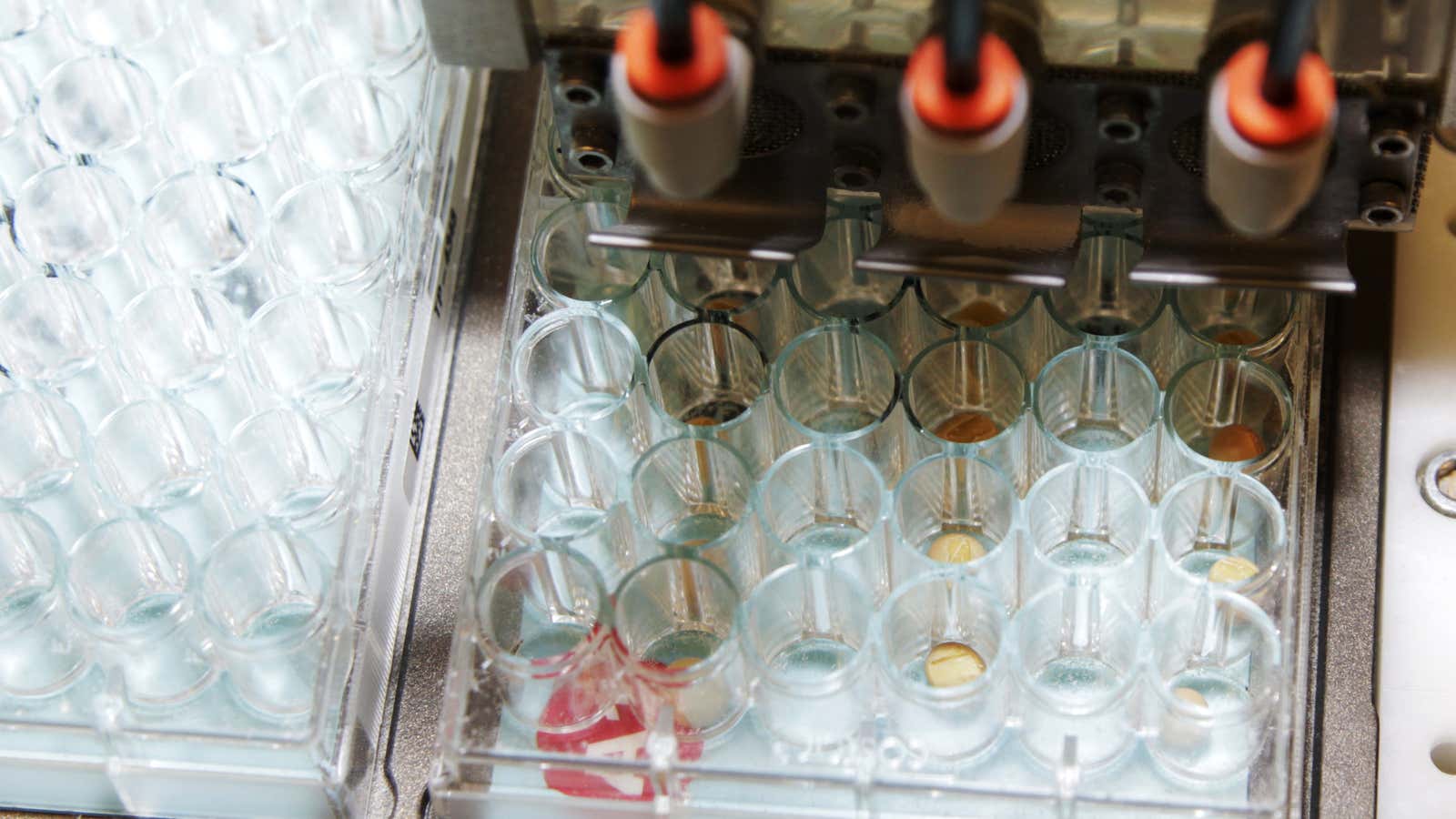

Both Color and Counsyl employ custom robots powered by in-house software, with 3D-printers to churn out tailor-made equipment. Machine learning algorithms help optimize operations and prevent waste. “When we started we actually assumed the the lab side of running clinical grade assays would be almost cookie-cutter,” says Laraki. “It turned out that was very much not the case. There’s a lot more work to do in the lab than expected and that turned out to be a very big opportunity for us.”

Once laboratories are run 24/7 by robots, say the companies, a cheap test available to thousands will become an even cheaper test available for millions. “Is software going to eat diagnostics? Yes,” says Eric Evans, the chief science officer at Counsyl. “Software will make it possible to do things that weren’t possible to do before.”

There will likely be some regulatory hurdles first. Although the US Food and Drug Administration is warming up to the idea of “direct-to-consumer tests” that meet their guidelines—and there are now more than 80 startups pursuing genetic testing, reports AngelList—the agency has lashed out at Silicon Valley before for jumping the gun with DNA-based services. The FDA slapped a moratorium on 23andMe’s health-related reports in 2013 after accusing the company of misleading customers about their health. In July, US healthcare agencies revoked Theranos’s license to operate its lab in California, and banned CEO Elizabeth Holmes from owning or operating labs for two years after the company was accused of causing “immediate jeopardy to patient health and safety” due to inaccurate blood test results. Most recently, the FDA pressured Theranos this August to withdraw a test for Zika. But federal regulators like the FDA still appear bullish on patient-requested genetic tests, saying in a press statement that such innovative services ”will ultimately benefit consumers.”

Breast cancer may be the point at which direct-to-consumer genetic testing tips. Not every genetic disease demands a universal test—tests are only useful when doctors can actually use the results to help patients. But those with the BRCA gene have an 80% risk of getting breast cancer, and doctors can reduce that number through mastectomies and other measures.

A low price should make testing everyone the obvious choice. Cystic fibrosis is a precedent. Testing for the disease was once only prescribed for caucasians or those with a family history of the disease, but by 2011 the process became so cheap (about $100 compared to more than $7,000 in the 1990s) that it’s now routine for all parents planning to have children.

“It is likely that within a few decades people will look back on our circumstances with a sense of disbelief that we screened for so few conditions,” wrote Francis Collins, the director of the National Institutes of Health in his books on genetic medicine.