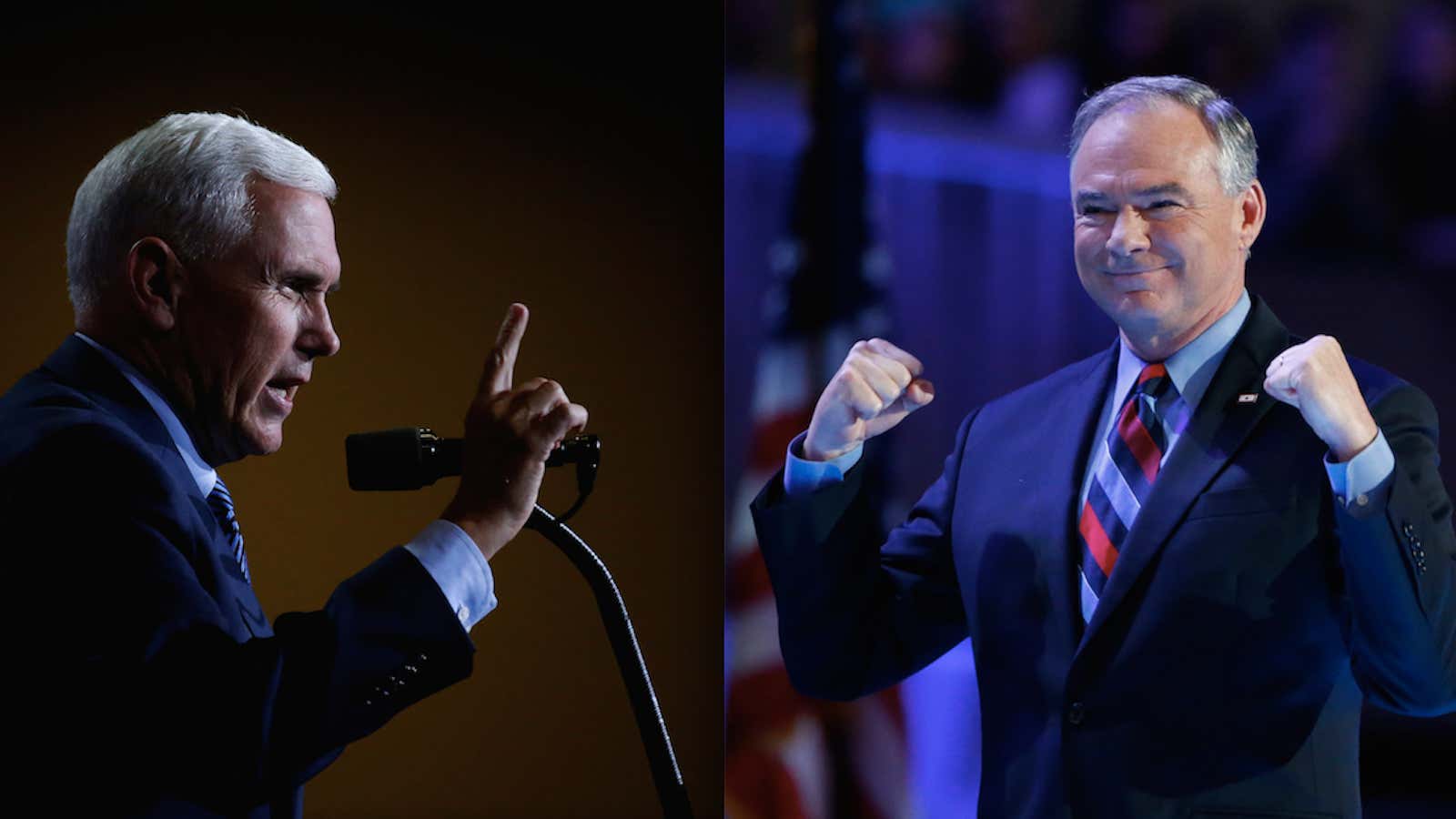

The vice presidential nominees will be squaring off on national television this Tuesday, Oct. 4. The debate comes eight days after a record-breaking audience tuned in to the fiery first battle between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton.

And yet, the very same pundits still obsessing over Trump’s spotty performance and Clinton’s polling bounce aren’t talking very much about the vice presidential debate. Indeed, according to the amount of mainstream coverage its received, the Tim Kaine vs. Mike Pence matchup this week appears to be a largely meaningless affair designed to give political reporters and pundits something to write about the next day. What little polling data we have seems to back up this assumption: In 2012, Gallup found that “past vice presidential showdowns have had almost no influence” on the way Americans vote in November.

In terms of viewership, the pundits may well be right—it’s highly unlikely that another 80 million Americans will end up watching Kaine and Pence argue over tax policy, relief for the middle class, and the temperament of their respective running mates. But while the vice president has long been caricatured as a glorified errand boy, especially in pop culture, this vice presidential election is shaping up to be one of the most important in many years.

Over the past two decades, the office of the vice president has grown substantially in terms of both staff and responsibility. The second-in-command is no longer just the guy who gives VIP tours of the Lincoln Bedroom. Instead, the vice president has become a principal player in national security bureaucracy, one of the president’s closest advisers during inter-agency discussions, and, in some cases, a vital deal-maker for bipartisan budget deals and Congressional negotiations.

Al Gore, Dick Cheney, and Joe Biden have all demonstrated the growing importance of the vice president in different ways. Al Gore may today be more closely associated with climate change activism and his tragic presidential run, but twenty years ago he was one of president Bill Clinton’s closest counselors on foreign policy and national security matters. When Clinton was wary of intervening in the Bosnian civil war, for example, it was Gore (in addition to then-secretary of state Madeleine Albright) who lobbied on behalf of a forceful US response. In an emotional address at the opening of the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, Gore made the moral case for Bosnian intervention, using the violent death of a 10-year-old child in Sarajevo to drill home his point. “This happened in our time, only weeks ago,” Gore said. “Must such horrors go on and on? They must not.” Two years later, Clinton lead a NATO air campaign against Bosnian-Serb forces, a military operation that pushed Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic to the negotiating table after three years of ethnic cleansing.

Gore helped promote a similar campaign in the 1990s when Haiti was in the midst of an increasingly deadly civil war. At the time, many in the Clinton administration were concerned that US military activity in Haiti would make the humanitarian situation worse. The logistics of intervening on an island in order to force out a dictatorial regime, they said, were complicated. But Gore pushed for the opposite, publicly noting America’s military options would remain on the table if junta leaders did not leave of their own accord. Clinton ultimately issued an ultimatum that convinced the Haitian regime to step down. Former United Nations ambassador Bill Richardson summed up Gore’s influence during the Clinton administration this way: “The vice president was usually the last person he talked to before reaching a foreign policy decision.”

Meanwhile Gore’s successor, Dick Cheney, is commonly regarded as the most powerful vice president in the history of the United States. Like Gore, Cheney cemented himself as an alternative power structure within the George W. Bush administration—a man who would keep quiet during large meetings but dispense advice freely when alone with Bush in the Oval Office. Cheney stands as historians’ best example of how a strong vice president can persuade his senior partner to go in a specific direction on policy. From the opening of the Guantanamo detention facility to the NSA wiretapping program, America’s use of enhanced interrogation techniques, and the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, Cheney is connected to many of the Bush administration’s most enduring policy decisions. As the Iraq war turned into an unpopular quagmire during his second term, his influence within the Bush administration narrowed. But Cheney was never really that far from Bush’s ear.

Joe Biden has maintained the vice president’s power over the past (nearly) eight years, even if he has not expanded the office by much. Intractable and unglamorous problems such as Iraqi politics and the ongoing unrest in Ukraine have largely fallen under Biden’s purview. A former chairman of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Biden has spoken with top Iraqi officials dozens upon dozens of times at critical moments in the US-Iraq relationship, and he’s been an important liaison between the Obama administration and the Iraqi government. The same goes for Ukraine policy; it is Biden, not president Obama, who speaks with president Petro Poroshenko regularly and keeps tabs on his government’s attempt to diversify its economy, meet its commitments with Russia under the 2015 Minsk agreement, and prosecute corruption.

Biden has also proven to be an invaluable asset on domestic policy, working with congressional Republicans on budgetary and fiscal matters. When the government seemed potentially close to defaulting on its debt in 2011, or when it veered toward the fiscal cliff in 2013, Biden tapped into his personal relationship with senate minority leader Mitch McConnell to hash out an agreement and avert a national crisis.

Whether at home or abroad, it’s clear that the office of the vice president has outgrown its stereotypes. This isn’t Veep. And while it hasn’t happened recently, it’s not inconceivable that the vice president we elect in November could find himself in the Oval Office. Of the 47 vice presidents who have served since 1789, eight became president due to the death of a sitting president. Donald Trump is 70 years old and Hillary Clinton is 68. No matter who is elected, he or she will be among the oldest elected chief executives, a slightly macabre but not insignificant benchmark. In fact, Trump would be the oldest newly elected president in history.

All of which is to say that there are more than a few good reasons why American voters should tune in to the debate. Either Virginia senator Tim Kaine or Indiana governor Mike Pence will be charged with helping their bosses deal with difficult and pressing challenges, which include a potential US recession, growing income inequality between the American middle class and the ultra rich, police brutality and racial discrimination, ballooning student debt, resetting relations with Congress, ongoing unrest in Asia and the Middle East, the rise of ISIL, Brexit, and climate change—not to mention the fallout from one of the most contentious presidential elections in years. This year, more than ever, we should all care about the person sitting one heartbeat away from the presidency.