1. Facebook may have just set a record for becoming a bloated corporate behemoth in the shortest amount of time.

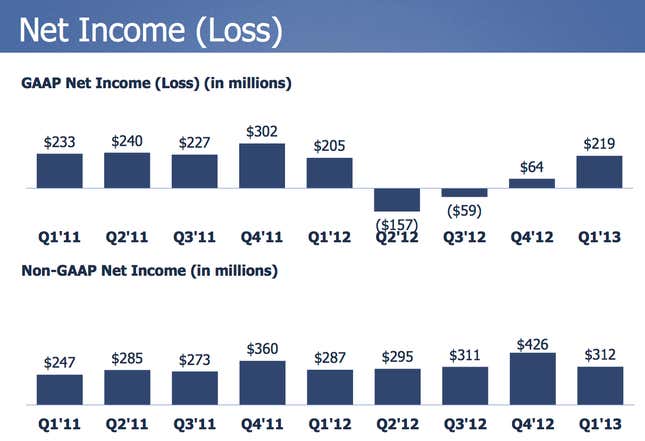

Facebook’s revenue is up 38% from a year ago, to $1.46 billion. But that hardly matters because the company still doesn’t appear to know how to really boost its profits—net income is more or less the same as it always was. (Which also means it’s a smaller proportion of revenue than ever.)

What’s keeping profits flat is Facebook’s accelerating spending spree. Expenses were $1.08 billion, up 60% from the first quarter of 2012. Facebook says that’s due to “infrastructure expense and increased headcount.” But these expenses are driven almost entirely by the arms race against Google and other companies to hire top engineering talent.

Here’s the proof: Facebook spent 28% less on buildings and other physical stuff (i.e. capital expenditures) than it did this time a year ago. Of Facebook’s $1.08 billion in expenses, capital expenditures for the quarter were $327 million. That means $753 million of Facebook’s expenses are likely to be almost all soft costs, which are, by the company’s own admission, almost exclusively payroll. (I’ve reached out to Facebook for clarification on this point and will update if they respond.)

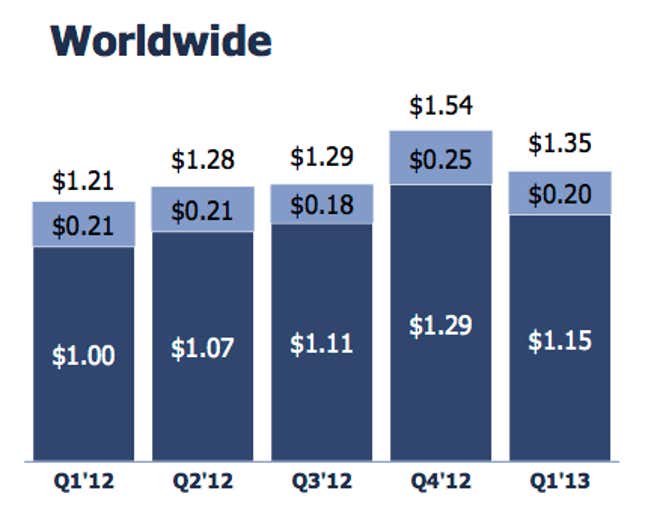

2. Facebook’s global revenue per user is down more than it should be.

This one’s genuinely shocking, but only if you’ve been listening to the narrative from Facebook itself. (Mark Zuckerberg’s statements in last quarter’s earnings call about how the company had only just begun to maximize advertising revenue being a prime example.) As I have predicted before, as Facebook gains more users in the developing world, any possibility that the company can start to make more money on each individual user—which is absolutely essential for growing its overall business—becomes increasingly remote.

Of course, advertising is a seasonal business, and some decline in the first quarter is to be expected. Compared to the same quarter last year, Facebook’s average revenue per user grew. But the quarter-over-quarter decline was still steeper, in both nominal and proportional terms, than what Facebook experienced a year ago.

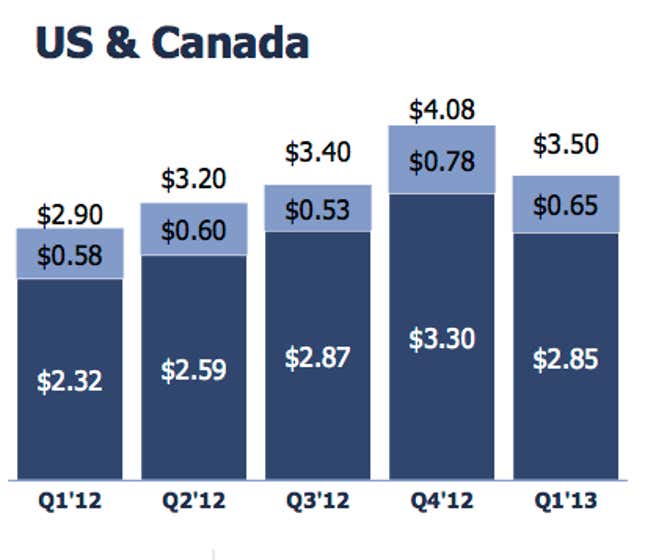

But it’s even worse than I’d originally hypothesized: Most of the decline in revenue per user happened not among Facebook’s growing—and aggressively pursued—user base in emerging markets, but in the US and Canada, where Facebook is the most well established, has the deepest relationships with advertisers, and should be increasing revenue per user. If, that is, the company’s plans were working as promised.

Another problem is that as the company’s head count swells, Facebook’s revenue per engineer does not appear to be advancing at nearly the rate one would hope for, if talent really equated to success. (It’s likely that Facebook’s revenue per engineer is actually declining, though it didn’t give an exact engineer count with its earnings.) As I’ve noted previously, “Facebook is a large, inefficient engine for transforming electricity and programmers into a down-market place to sell low-value advertising.”

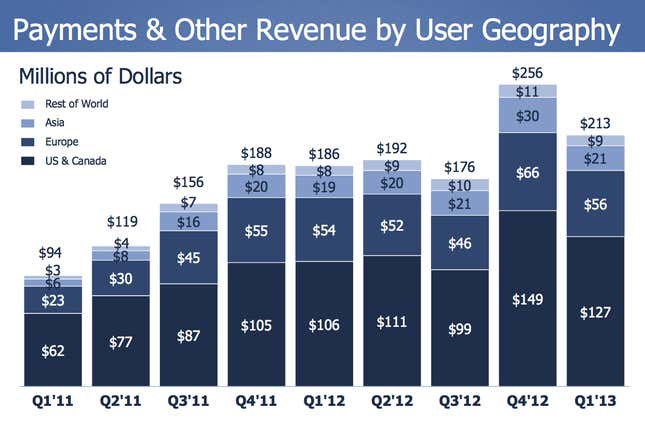

3. Facebook’s revenue from non-advertising sources—the ones that were supposed to diversify its sources of income—are down for the first time in a year.

[Update: As John Milani has outlined in this illuminating post, Facebook’s payments revenue of the fourth quarter of 2012 was artificially inflated by an accounting issue. The bottom line, after this adjustment: Facebook’s payments revenue remains basically flat across the past 5 quarters, and, as he notes, “illustrates a lack of revenue diversification, which is a liability for the company.”]

So much for Facebook capitalizing on the current hype for virtual currencies—or, in other words, finding ways to get users to part with actual money to use its social network. Facebok credits, which users can redeem in games and for virtual goods, appear to be losing popularity.

There is some seasonality here—the first quarter of the year is always down compared to the last quarter of the previous year, since the last quarter is when North Americans do a lot of shopping. But this year that drop was 16.7%, whereas at the beginning of 2012 the drop in spending on Facebook credits was just 1%.

4. The shift to mobile is killing Facebook’s ability to make a profit.

If you want to know why Facebook’s revenue per user and payments income are down, here’s your smoking gun.

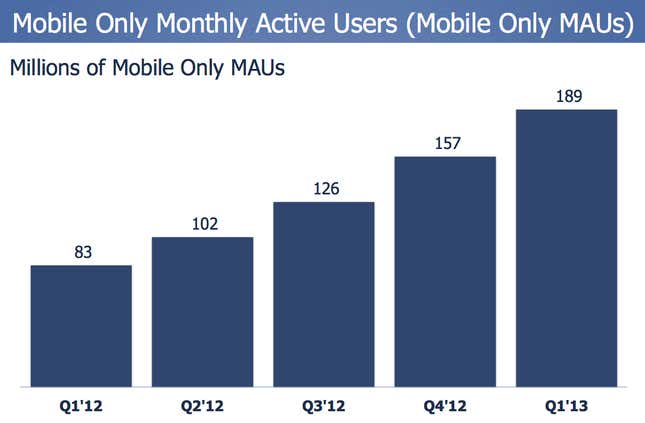

Facebook added 54 million “monthly active users” since last quarter—which is about what the company has added every one of the last five quarters, in what has proved for over a year to be strictly linear, and decidedly not “viral” growth.

In the same period, Facebook added 32 million “mobile only monthly active users” — in other words, people who visit the site at least once a month, but exclusively from their mobile device (like a smartphone). This means the majority of new users Facebook added in the last quarter—59%—do not ever visit the desktop version of the site.

The shift to mobile could also explain why Facebook is having trouble generating significantly more revenue from all the talent it’s hiring. Again, from my previous analysis of Facebook’s prospects for justifying its initial share price:

Most of Facebook’s engineering resources appear to be devoted to simply keeping up with users, giving them ways to access Facebook on every newfangled device. It’s hard to argue that the company has done anything particularly innovative since its founding; all the updates to Facebook since then come down to tweaks to the core experience of reading through a stream of updates from your friends.

Since I wrote that, Facebook introduced Graph Search, which is interesting but marred by the usual privacy concerns that are likely to prevent from Facebook from making money on it in ways that are significantly different from how the company makes money on existing pageviews.

5. Unlike Google, Facebook is stuck with many users who come to the site in a mood to see anything but advertising.

Facebook would probably argue that the company is investing for future growth. That, like Amazon, their focus right now is on market share, not profit or even revenue. But the question, as always, is how does Facebook make money even if it touches every person on earth?

This is the most basic issue Facebook has, and the one that its boosters ignore when they wax rhapsodic about how “owning the social graph” will some day turn Facebook into a company that prints money on the scale of, say, Google.

When users visit a search engine, they are often in the mood to spend money. They may be researching a purchase or searching for local merchants. Other than seeking news or satisfying basic curiosity, almost all the uses of search are a prelude to an exchange of money. Google and Facebook are similar—both are making money almost exclusively on advertising. The difference is that while Facebook is pushing banner ads and product endorsements in between conversations with friends, in a way that can feel intrusive, Google’s ads arrive just when people are amenable to hearing their sponsors’ message.

If cat pictures and status updates were a good business, the important measures of Facebook’s revenue would all be advancing. Instead, shockingly, they are waning. This should be a wake-up call to investors and Facebook’s leadership.