“Slang dictionaries have always been done by mad people who sit in rooms and make books out of them,” explains Jonathon Green. For 35 years he’s been doing just that: collecting slang words and compiling them into dictionaries.

The biggest of these—Green’s Dictionary of Slang, published in 2010—launches online today (Oct. 12). The online version is made up of 132,000 terms (the original print edition had around 110,000). Users can search for a word and its etymology for free, and subscribers can pay to access a bigger range of citations and a timeline of their evolution.

Finding hundreds and thousands of slang words isn’t a straightforward affair. There is, Green says, “an element of dropping the stone in the pond and seeing where the ripple takes you.”

He sifts through newspaper archives, picking out, say, a columnist from the mid-20th century and reading through their work to pluck out specific terms to trace. He’ll trawl through lyrics, film and TV scripts, fiction, bibliographies in other authors’ books, and box sets—he once watched the entirety of The Wire, and as soon as a word came up, he’d stop, go back, transcribe, and trace it. That particular exercise threw up over 400 citations.

“I need something I can quote, [so] it has to have been recorded,” he says, explaining why he doesn’t do fieldwork. It’s also hard to extract slang. For some people it’s “simply the language they speak and the words they use,” he says. Grasping slang is not so much about getting up to speed with modern or “youth” speech, but observing the latest lexical twist on something.

With that in mind, lexicographers keep looking for older citations—one of Green’s rules of slang is that a word is “always a bit older than you think it is.” The verb “to dis”, for example, has roots earlier than 1980s hip hop. Its first mention was in an Australian newspaper in 1905.

Slang is also a window into how some words fall out of circulation entirely, while others just don’t go away. Green cites “cool,” which first cropped up in 1766, as one that still holds today. Then there are the words that change meaning. In addition to meaning stupid, “bonkers” also meant mildly drunk in a 1984 citation; a definition that is less widely used 32 years later. In the 17th century, “a fizzle” referred to breaking wind; two hundred years later, it evolved to mean a failed task.

Why is slang, vaguely defined as a set of informal words and phrases, so interesting? For Green, it’s “a language that expresses us at our most human.” When we use slang words—for sex, body parts, or insults—we’re talking in our “most honest and most human way.” There’s also something subversive and rebellious about it. Green calls it “counter-language.”

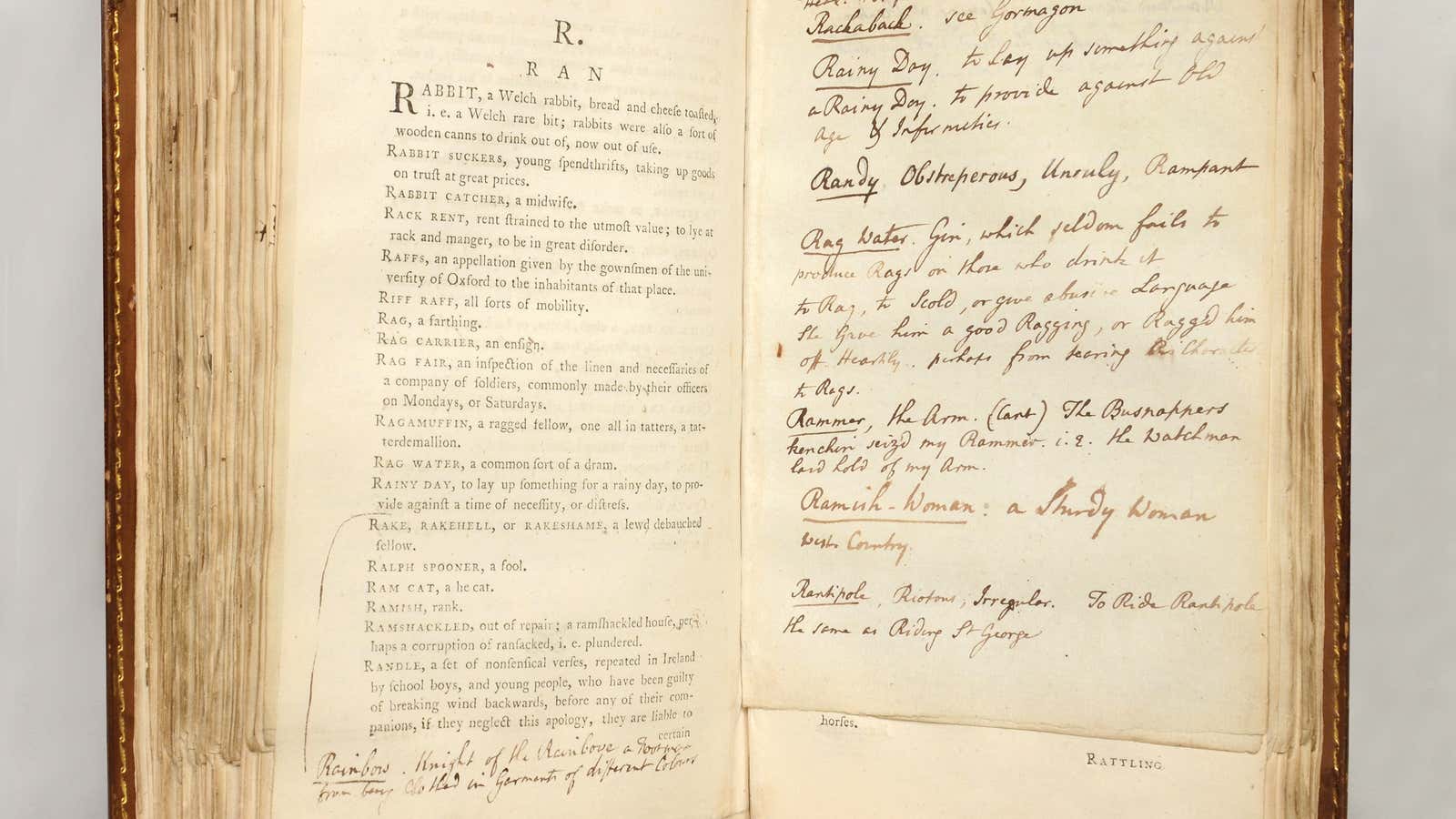

Slang didn’t originate as slang. Terms for body parts and bodily functions began life as words people used every day; they only became “problem words,” Green explains, in the mid-late 18th century when Britain tried to rival the Académie Française—the guardians of the French language—in its efforts to better document English. Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language, first published in 1755, is one example.

Out of the hundreds of thousands of terms, does Green have a favorite? “It’s the one I didn’t know before but just discovered,” he says somewhat evasively. It’s “clatterdevengeance,” a 17th century word for penis.