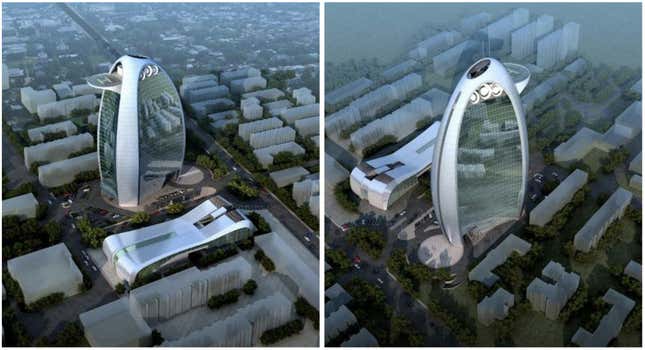

The shape of the new headquarters for the People’s Daily, China’s official government newspaper, is meant to symbolize earth and sky, or from an aerial view, the Chinese character for the word for people (人). Recently Beijing residents have observed that from one angle the unfinished building looks like, well, something else. After bloggers on China’s Sina Weibo joked that it fits thematically with Beijing’s CCTV building, often compared to a pair of boxer shorts, Chinese censors began blocking searches (paywall) for “People’s Daily Building” last week.

While the unfortunate visage of the People’s Daily building is only from the backside of the larger sloping but squarish structure, the building is one of several massive architectural works of questionable design that are meant to symbolize the power and advancement of China and the Chinese government. Ever since the plans for the People’s Daily headquarters were unveiled in 2009, it has been ridiculed by Chinese online bloggers for resembling a giant juicer or a chamber pot.

Bizarre buildings have increasingly been piercing China’s skylines, earning the country a reputation for being “a playground for bad design.” Unattractive Chinese buildings have become so commonplace that a Chinese architectural firm, Archcy, has started surveying residents on what they believe are the country’s 10 ugliest buildings (article in Chinese). One architect last year said choosing just 10 was “very hard” but a million he could do.

Why does it matter if China seems to have a penchant for large, garish buildings? For government projects like the People’s Daily, ridicule can easily turn into a discussion of how public funds are spent. Last year, the city of Fushun spent approximately 100 million yuan ($16 million) on a building in the shape of a giant steel ring, covered in LED lights. The building’s name “Ring of Life” was a top trending discussion topic on Sina Weibo, with one blogger writing, “All these millions, how many kids will be able to go to school with that amount of money?” Another questioned whether government corruption may have been behind the project. “Do the officials who approved this dare to publicize their accounts?” the blogger asked.

Indeed, it’s striking that local governments and private developers, which have money, manpower, and often the ability to build almost wherever they please wouldn’t be building more structures with world-class design. In a 2004 article on the power of aesthetics and architecture in China (article in Chinese), cultural critic Zhu Dake wrote that China’s weird skyscraper craze was “not only creating a huge amount of concrete garbage, but also posing real damage to the government’s image.”

The reasons are likely several. For one, China is in the middle of a mass migration of residents from rural areas to urban centers and a building boom where development plans often happen so fast that considerations for design, technology, and quality are sacrificed for lower production costs and speed.

At the same time, Chinese governments are commissioning projects they believe will bring renown to major cities like Shanghai, Beijing, and Tianjin as well as second- and third-tier cities. The result, according to critics, is that China is flooded with projects focused on flashiness and scale. In 2012, China was home to 20 of the world’s tallest skyscrapers being built, and the lesser-known city of Changsha pledged to build the world’s tallest building, with 220 stories.

Another factor is that China’s modern architectural sensibility, in some ways, is still in its infancy. The industry has only begun emerging over the past 30 years during the country’s economic reform and opening up, after decades of following Soviet-style city design. Today, there is about one architect for every 40,000 people in China. (In Italy, the proportion is more like 1:400). And the newness of it all, Wu Liangyong, a member of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Chinese Academy of Engineering said, means the People’s Republic is now seeing a surge of demand for the avant-garde and novel—no matter how tacky.