Even during the best of times, observers take China’s economic data with a healthy pinch of salt.

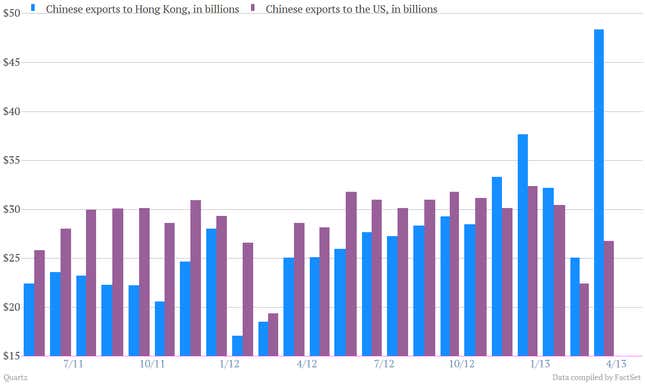

But in recent months, Chinese import and export numbers hit something of a high-water mark for implausibility. For instance, according to the most recent monthly numbers, China exports almost twice as much to Hong Kong—a financial citadel of around 7 million people—as it does to the US, the world’s largest economy and a voracious consumer of Chinese manufactured goods. Seriously, look.

Obviously, this isn’t right. The one theory is that the spike in “exports” to Hong Kong is the aggregate result of widespread fraud among exporters, who are enabling foreign investors to sidestep government attempts to control the flood of cash into China’s fast-growing economy. Apparently the Chinese government thinks that’s a possibility.

This weekend China’s chief currency trading regulator, the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE), announced it plans to clamp down on capital inflows, including increased monitoring of cargo and cash flow data to make sure the numbers match. The yuan weakened in response, as some of that inflow of cash from abroad has doubtlessly been responsible for the heavily controlled currency hitting all time highs recently.

Now a good question might be: Why does China want to keep such tight control over how much investment cash gets into the country? Isn’t incoming capital a good thing for investment and development? Not always. There’s a rich history of hot developing markets sucking in way to0 much cash, too quickly, pushing asset prices up sharply and then seeing those asset prices collapse once those flows of cash reverse. That’s the short version of the East Asian crisis of the late 1990s. China has tried to prevent a replay. However, keeping investor money out of a fast-growing economy—especially when interest rates, and by extension yields on investment are near all-time lows—is a challenge. “If money wants to get in, it’ll get in,” an unnamed trader told Market News International. And once it gets in where might that cash go? A good part of it likely ends up in China’s burgeoning financial black market, something financial analysts are increasingly concerned about.