Time and time again this election season, Donald Trump has lambasted the “dishonest” and “corrupt” media for poisoning voters’ minds against him.

The Republican presidential nominee may be the most emphatic about it, but he isn’t the only person uncomfortable with how much sway the media has. Two-thirds of US voters surveyed by pollster Rasmussen Reports (thought to be Republican-leaning) said they thought the news media had too much power and influence over elections, according to a report released in February.

But how much does the media really influence voters’ decisions? Can it actually rig an election?

The short answer is: unclear. But major developments in stories tied to the presidential candidates—stories about the Clinton Foundation and Trump’s tax returns among them—do appear correlated with slight fluctuations in voting decisions, according recent data by analytics platform Parse.ly.

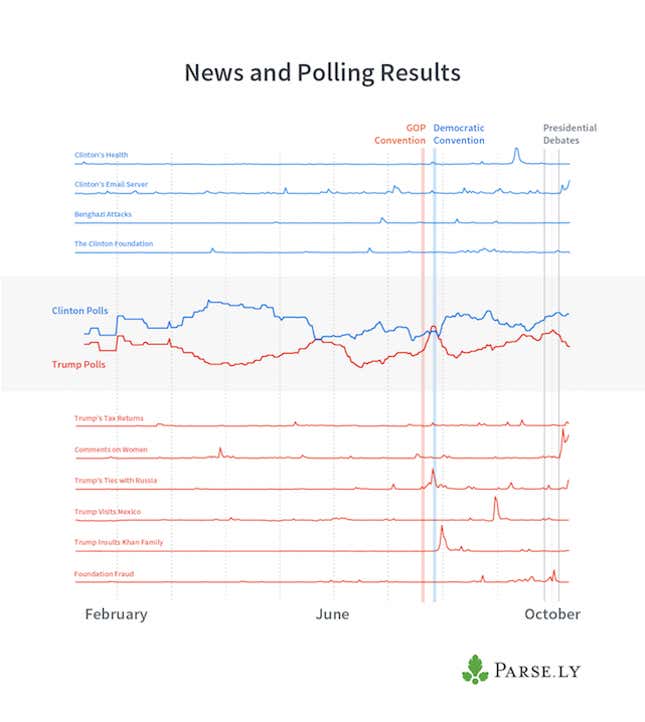

Parse.ly’s data scientists looked at page views for coverage related to 10 major news events, including the Clinton email scandal and Trump’s taxes, across the 170 media companies and 700 websites that use its service (Quartz included). They then compared that traffic to Real Clear Politics’ national poll averages for the US presidential election to see how coverage aligned with voter support for Clinton and Trump. The data covered events from September 2015 through mid-October of this year. Here’s a snapshot:

According to the company’s findings, the Democratic and Republican national conventions bolstered the poll averages for both Clinton and Trump, respectively. Parse.ly data analyst Conrad Lee says that’s normal: Voters who vote along major party lines tend to line up behind their respective nominees after the conventions.

Trump has experienced a few hiccups in the past year. As traffic rose on negative stories—about his ties to Russia; about the insults he levied at the family of an American Muslim soldier killed in Iraq—the Republican candidate fell sharply in polls. Some 45.7% of US voters surveyed in late July said they would vote for Trump; by early August it had dropped to 39.9%.

But even dramatic fluctuations appeared to smooth out quickly, and didn’t have lasting impact. Trump’s poll average rebounded to about 42% by the end of August, and 45% by Oct. 2. It dipped again the following week, landing at 42% on Oct. 11, the final day recorded in the study. That was after the second presidential debate and after the release of a taped lewd conversation Trump had about women in 2005.

Clinton has experienced similar seesawing. Her poll averages dropped from 44.9% in mid-September after a bought of pneumonia raised questions (and spurred news stories) about her health. But support recovered quickly; Clinton’s poll average was back up at 46% by Sept. 22, alongside small traffic bumps for coverage related to her email scandal.

Overall, there were larger traffic spikes to stories about Trump controversies than Clinton controversies, at least during the period observed and at the publications studied, which could have contributed to Clinton’s stronger poll numbers.

The research did not look at the effect more routine coverage—of the candidates’ policies and stances—had on voter support. But studies have found primary-season ties between how often a candidate is mentioned in the media and his or her strength in national polls.

Bottom line: The limited number of swing voters left at this point in the race may mean the media is having less of an impact, but narratives built up in media coverage can manifest themselves in polling. More specifically, coverage of major scandals and news effects tied to the candidates can have a small measurable effect on voter decisions.

Is that a “rigged” system? You decide.