Just 10% of people aged 20-24 are out of work or not in school in Germany. As befits Germany’s reputation for efficiency and industrial success, this is one of the lowest levels in the world. If all 35 OECD countries reduced youth unemployment to German levels, the economic gain would be $1.1 trillion, according to a study by PricewaterhouseCoopers.

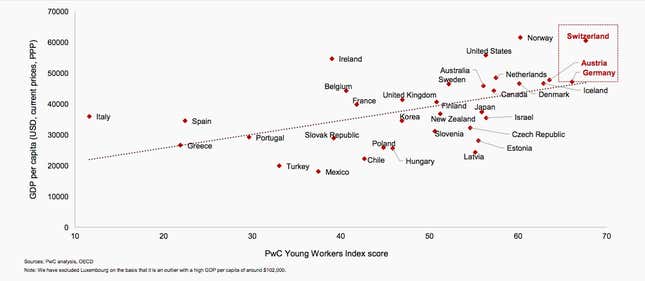

Switzerland ranks top in PwC’s “Young Workers Index,” which compares eight different measures of employment and education. Germany comes second. The US is number 10 on the list and the UK is 21st. Southern Europeans have fared the worst, showing the long-lasting impact that the financial crisis and European debt crisis have had on young people there. Italy came in last on the index, where 35% neither have jobs nor are in school. If Italy improved to Germany’s level, its GDP could increase by $156 billion, the report said. A separate report published last week showed that one in 10 Italians under 34 are living in poverty.

Why do countries like Germany and Switzerland perform so much better? Their governments run “dual educational systems” that incorporate vocational training into formal education to better prepare young people for jobs–businesses also actively target young people. In Germany a Vocational Training Act has provided 500,000 company-based training contracts a year. Finally, Germany and Switzerland recruit people from a wider variety of economic backgrounds by reducing informal hiring and the use of qualifications as a filter in the recruitment process.

The PwC report highlights the UK, where 17% of young people aren’t in work, school or training. If that fell to 10%, Britain could add £45 billion ($65 billion) to its economic growth, or 2.3% of GDP, the report said. Part of the problem in the UK is the social stigma attached to vocational training; apprenticeships aren’t considered valid career paths. This has helped create a gap between the skills the UK needs and the ones its young people have. Between 2005 and 2010, 59% of graduates were in jobs that didn’t require a degree.

The UK government is trying to fix this problem and wants apprenticeships to have the same social and legal value as a university degree. It plans to boost the number of new apprenticeships by 3 million by 2020. Countries at the top of PwC’s index also had the highest GDP per capita. But it doesn’t come cheap. These same countries spend the most on education.