Two hours outside of Guatemala City, a winding road leads to a weathered church in the center of Patzún, Chimaltenango, a predominantly Kaqchikel Mayan community. The small city is lined with electronics shops, ATMs, and mom-and-pop corner stores; outside the church, women dressed in traditional Mayan textiles, floral woven tops, and brightly-colored striped skirts sell tortillas, fruit, and small trinkets at covered stalls. Even after a period of state repression against indigenous people during a 36-year civil war that ended in 1996, the predominantly Mayan population has preserved certain traditions, including the ancestral medicinal practices.

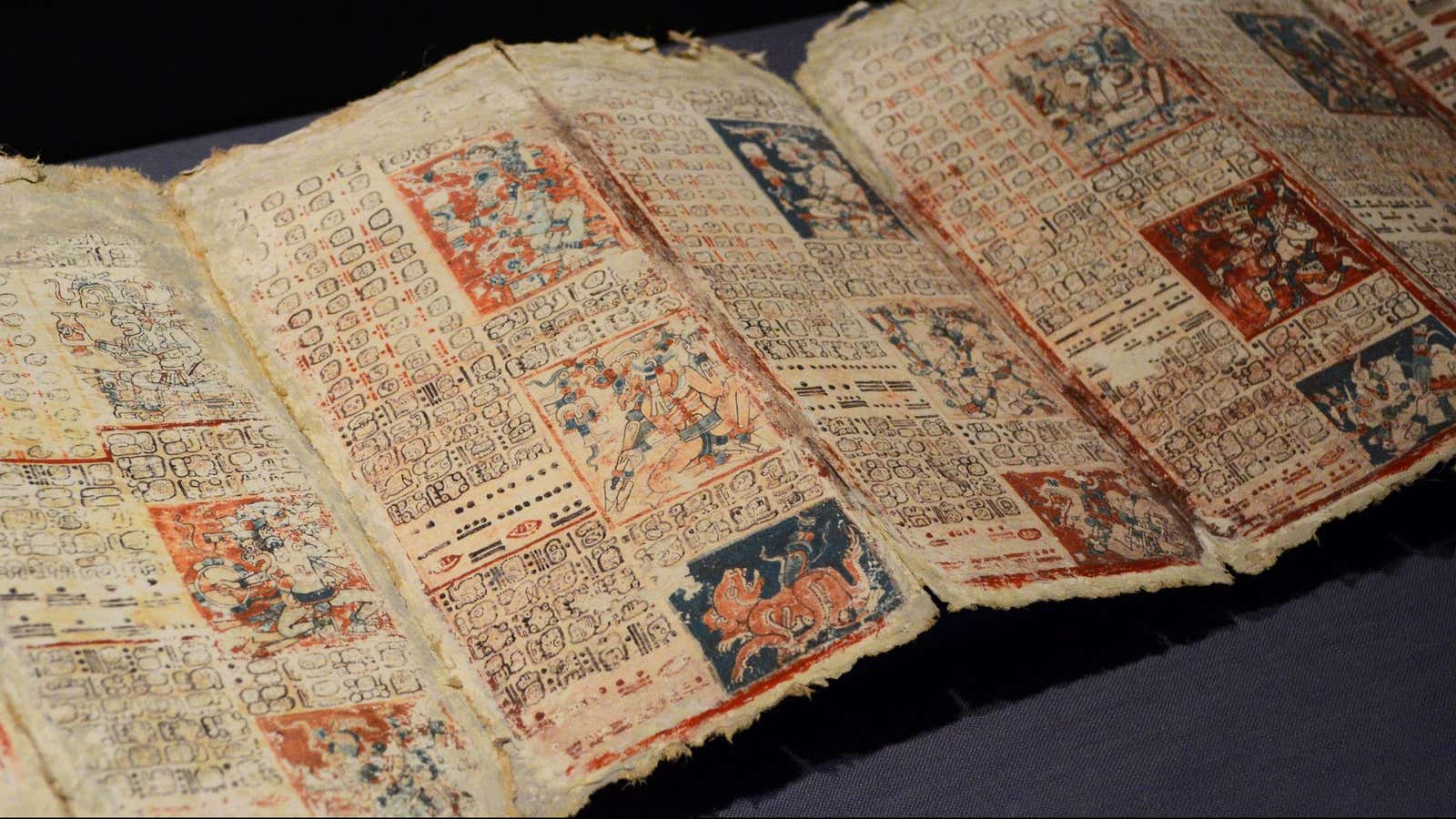

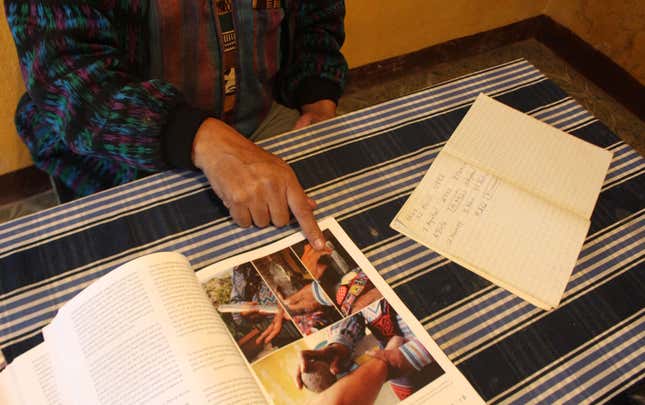

Here in Paztún, Simeon Taquira see patients at his home office, a small room with only a wooden table, two chairs, and some decorations hanging on the orange walls. Taquira leans back in his chair as explains his medicinal methods in slightly-accented Spanish that reveals his native Kaqchikel. Over his left shoulder hangs the Mayan calendar, the foundation for his work as a healer.

Taquira is one of thousands of Mayan spiritual guides in Guatemala. He treats at least 100 patients each month, addressing health problems from headaches to cancer using spiritual and natural medicinal remedies. His most important tool is not a stethoscope or thermometer. Instead he is guided by a patient’s quadrant, a grid of Mayan astrology symbols determined by date of birth which reveals personality and disposition. By applying the Mayan cosmovision, Taquira can determine which illnesses and diseases a patient is particularly vulnerable to based on their quadrant.

“I take out your quadrant and I detect that you are very sick,” Taquira said. “Another doctor takes an X-ray and he tells you that you don’t have any sickness and that you are healthy. But you are suffering inside and the X-ray doesn’t show it.”

In parts of Guatemala without indigenous roots, Mayan medicine is often written off as backwards, superstitious, and unscientific, says Alejandro Cerón, a researcher at the University of Denver who has studied indigenous health in Guatemala. Some call it witchcraft—a term Cerón says is rooted in the country’s historic racism and marginalization of Mayan people and their practices.

“The Catholic and Evangelical religions said that we were witches and that our practices were satanic, but it’s not true,” Taquira said. “We use the knowledge [of the Mayan calendar] to help other people. We consult and respect the patient and ask for their permission to participate. It’s different from the occidental methodology.”

In Guatemala, more than 50% of the population has indigenous roots. Here and in many parts of the developing world, traditional medicine retains a strong presence. The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed a traditional medicine strategy, designed to increase awareness and understanding of these practices so that they can be recognized as valid medical and cultural responses to worldwide health problems.

Instead of writing off Taquira’s methods as backwards, Western-trained doctors can learn from his approach regardless of whether they believe in the Mayan spiritual beliefs that drive the system or the herbal remedies he employes. The key is that Taquira spends enough time with his patients to actually understand what is happening in their lives—and that can lead to better care.

The Western approach to medicine focuses on speed and efficiency; in the US, more than 85% of patients spend less than 25 minutes with their doctor during a visit, according to a Medscape report. Many patients spend even less time with their physician, with hospitals scheduling appointments at 15 or 11 minute intervals.

To provide adequate care, the scientific literature suggests, primary care doctors should spend almost three times as much time with patients as they do now. Rushed visits leave many patients frustrated, negatively affecting the patient-doctor relationship that is crucial to providing patients with quality care.

Taquira and other Mayan healers often spend an hour or more with their patients. This allows them to consider the spiritual, interpersonal and societal factors that could be causing health problems.

“In the Mayan system, symptoms are like a door and you can open that door and see all this myriad of different issues that are happening to the person,” says Ana Vides-Porras, co-author of Relationships that Heal: Beyond the Patient-Healer Dyad in Mayan Therapy. Western medicine relies on blood tests, X-rays and CT scans—great for defining an illness but ineffective in diagnosing underlying problems like the impact of poverty, family upheaval, or work stress. And yet social factors, including class, education level and personal relationships, affect almost any illness or health condition, from diabetes to life expectancy to maternal mortality.

“A general criticism [of modern medicine] is the tendency to decontextualize the patient and to try to see the patient and the patient’s symptoms out of context without paying attention to family situations or other social situations that are happening,” Cerón says. “In my experience the Mayan model of healthcare pays attention to that kind of contextual information.”

Just as biomedicine relies on a system of values to determine illness, so does Mayan medicine, says Vides-Porras. Taquira commonly treats “el susto,” which translates literally as “the fright,” a supernatural illness that occurs when a person becomes scared or anxious. That feeling then stays inside their body and can manifest as a headache or bodily aches and pains. A person can contract “mal de ojo,” or the evil eye, after interacting with someone who transfers too much energy to their body. This can cause an internal energy imbalance leading to physical pain throughout the body.

In August, Guatemala’s health minister announced an initiative to recognize supernatural illnesses in the public healthcare system. Through this program, practitioners will work with traditional Mayan healers to determine a medically and culturally comprehensive approach to a health problem when a patient comes in complaining of “el susto” or “mal de ojo” rather than deny it.

“Within the Mayan system, they believe that you cannot separate the spiritual world from the physical world, so diseases and illnesses are affected by both physical or spiritual situations,” says Walter Flores, director of the Research Center for Equality and Governance in the Health System. By rejecting the legitimacy of these diseases in health centers, practitioners are isolating patients, he adds. This behavior chips away at the trust that is so crucial in the doctor-patient relationship.

Instead, doctors should take the opportunity to understand their patient’s illness and work within a social context to solve it. “If the disease is considered supernatural in origin, the whole family and [social] system needs to work together to reestablish the balance,” Vides-Porras says. Likewise, for patients from Mayan communities that place importance on social systems in the healing process, separating them from their networks can be detrimental to their health. Vides-Porras saw this in action while working with cancer patients in Guatemala. Spending more time with their family and wider support circle improved their health and response to treatment, she says.

This cultural importance of larger social networks is not unique to Guatemala. Western medicine has started to recognize the value of personal support systems and spirituality in health care. Extending visiting hours has been shown to reduce length of stays and improve patient wellbeing. Patients who pray while recovering from surgery report lower pain levels.

In rural Guatemala, 70% of women who give birth each year choose to do so accompanied by a comadrona, or Mayan midwife. Comadronas have limited formal medical training, if any. Guatemala still has one of the highest rates of maternal mortality in the region, yet the rate has decreased in recent years thanks to comadrona training programs that incorporate pillars of both Mayan and modern medicine.

Comadronas are trusted by the community and make their patients feel at ease. Doctors are trained to handle life-threatening complications during labor. But it has taken merging the two approaches merge to reduce maternal mortality, says Bernarda Méndez, head of maternal mortality and reproductive health at the Pan American Health Organization.

Comadronas can learn techniques to handle complications during birth and recognize when to send a woman to the hospital. In turn, formally trained doctors should try to model the way comadronas interact with their patients, Méndez says. Trust, after all, cannot be overestimated when it comes to healthcare. Without trust, doctors can’t do their job—patients who trust their doctor are more likely to seek treatment for HIV, vaccinate their children, or utilize preventative health services.

About 10 km from Paztún in San Juan Comalapa, women often go to comadrona Rosa Chex when they suspect they’re pregnant. The 60-year-old, five-foot-tall Mayan woman detects a pregnancy using the date of a woman’s missed period and by feeling around her abdominal to sense a change in energy.

Once Chex confirms that a woman is pregnant, her care becomes more personal. She focuses on getting to know her patient. Does she have a stable job or stay at home? What is her relationship like with her husband? Does she have any doubts or concerns about her pregnancy? These factors can affect a woman during her pregnancy and the baby growing inside her, Chex says. Her job is not only to deal with medical issues, but to calm, prepare, and advise future mothers. This extends until childbirth, when Chex goes to a woman’s house to soothe, encourage and care for her.

Maria Ana de Jesus Poyon Catu, a 40-year-old mother of 10, has given birth to almost all of her children at home with either Chex or another comadrona by her side. But she was transported to the hospital when had some complications during the birth of her youngest son, now a year and a half old. There, she felt scared and alone without the support of her family and a comadrona.

“Why do we call the comadronas? Because we trust them,” she says. “At the hospital with the doctor you feel alone.” The doctor didn’t ask her if she would like a glass of water or how she was feeling after giving birth.

Patients such as Poyon Catu still frequently call Chex and Taquira to deal with health problems. However, they also recognize going to a health center may be necessary in certain cases, including getting their children vaccinated. Is one system better than the other? The answer, of course, is neither.

“If we start building bridges across different systems,” says Vides-Porras, “we can help patients more than if we just stick to our own notions.”